Wherefore art thou Romeoville?

By Katie Klocksin, Logan Jaffe

Wherefore art thou Romeoville?

By Katie Klocksin, Logan JaffeIt’s a feat of imagination to look beyond modern developments in your town, suburb or neighborhood and picture how the place looked as it was getting its start. Even if your neck of the woods has no historic district or a single century-old home, it’s still got a history. And, often, its starting point is somehow tied up with its name.

Paul Kaiser is particularly interested in the starting point of his adopted home of Joliet, the largest city in Will County. His question for Curious City goes back decades, when he first encountered an odd, name-related fact about Joliet and its apparent relationship to a village just north, Romeoville:

I believe that Joliet was once named Juliet, while nearby Romeoville was once named Romeo. What’s the story?

To find an answer for Paul, we found historians (both past and present), a linguistics professor and a Shakespeare expert to consider the relationship between the original town names. As we looked at the towns’ broader history, we found we were able to fill in at least some blanks left by a lack of documents. But more importantly, we learned why origin stories can still be useful to our own identity, even if you can’t nail these stories down so tightly.

What we know

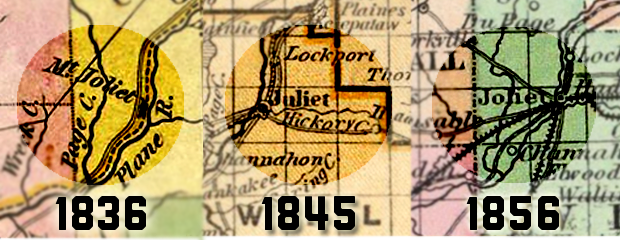

Paul’s onto something, at least when it comes to the two core details. Back in the 1830s, Joliet was founded as Juliet, and Romeoville was founded as Romeo. (Some sources also call the town Romeo Depot.) You can even see the names on old maps of the area … which is cute and all, considering they bear an obvious resemblance to William Shakespeare’s star-crossed lovebirds, Romeo and Juliet. There is, however, no solid documentation — no municipal meeting minutes nor history accounted for by town founders — that unequivocally lays out why these towns were named as they were.

But there are some worthy speculations. Your best bet is to head back 150 years or so before the towns were named by white settlers. In the 1670s, French explorers Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet were traversing parts of the Great Lakes region, in part to find out if the Mississippi River flowed to the Gulf of Mexico or the Pacific Ocean.

In May of 1673, just southwest of present-day Chicago, they stumbled upon a huge mound near the Des Plaines River. On their maps, Marquette and Jolliet christened the landmark Mont Jolliet, and the name stuck. The name later morphed to Mound Joliet.

About 150 years later, the area was drawn into an ambitious plan by the U.S. government, the newly-formed state of Illinois, and investors to build the Illinois and Michigan Canal, a waterway that would connect the Great Lakes to the Illinois and Mississippi rivers. When completed, materials could be transported quickly, compared to the era’s cumbersome overland routes. The federal government ceded land surrounding proposed routes, and lots were sold to fund canal construction.

James Campbell, treasurer of canal commissioners, bought a bunch of land in the Mound Joliet area. Except, for one reason or another, the area at this time became known as Juliet — with a U. This is where history gets wonky.

Even historians from the late 1800s (including those writing just a generation or so after Campbell) can’t offer much insight into Juliet’s origins. In his 1878 book History of Will County, Illinois, George Woodruff throws his hands in the air:

Campbell’s town was recorded as ‘Juliet,’ whether after Shakespeare’s heroine, or his own daughter, or by mistake for Joliet, the writer cannot determine. There are various theories; take your choice.

We encountered three theories that account for the original name of Juliet, as well as some kind of relationship with Romeo.

The typo theory

Our question-asker, Paul, is familiar with the explorers Marquette and Jolliet, and he speculates that the town was named Juliet on maps, due to “possibly human error on some of the map making. Where things just morphed to what somebody wanted it to be.”

We can find no record of cartographers of yore owning up to such a careless error. But Edward Callary, a linguistics professor at Northern Illinois University who wrote a book on Illinois place names, entertains the idea from an oratory standpoint. He says it’s possible that 19th-century map makers may have simply not known how to translate the French-sounding name Jolliet into English. So, when marking the spot of Mound Jolliet, it’s possible they made spelling errors. And if that’s the case, Callary says, it’s also possible those spelling “errors” were more like willful oversights.

“We sometimes make up things that are a little bit closer to words that we already know rather than ones we don’t know,” Callary says.

For example, ever hear of Illinois’ Embarrass River? Callary points out the name comes from Americans reappropriating the river’s French-given name, Embarrasser, which meant “obstruction” at the time.

The daughter theory

However, Sandy Vasko, the Executive President of the Will County Historical Society, is a proponent of what we call the daughter theory.

Remember land-buyer and canal treasurer James Campbell? Several sources suggest that he may have had a daughter named Juliet, and that when forming a town, he named it after her.

Ironically, the earliest suggestion of this comes from the same 1878 Will County history book we got our three theories from. In any case, the author writes:

On the 13th day of May, the Surveyor’s certificate was filed, and on the 10th of June, 1834, the plat was recorded and the town christened to “Juliet,” for Campbell’s daughter, it is said …

All of this is debatable, though, since we’ve also encountered history books that claim Campbell had a wife named Juliet, not a daughter. But Callary says that’s not possible.

“Campbell’s wife’s name was Sarah Anne,” Callary says. “He had no females in the family that were named Juliet that I can find. Maybe he named it for a friend’s wife or daughter, but he didn’t name it for his wife.”

The Shakespeare theory

At face value, the Shakespeare theory is simple: The towns Romeo and Juliet were platted around the same time and named, perhaps puckishly (as suggested by one our most prolific web commenters), as a pair in honor of Shakespeare’s star-crossed lovebirds. Some sources mention that either Romeo or Juliet were platted as a healthy competitor to the other.

There’s a complex side to the Shakespeare theory, though. To understand why Shakespeare characters would even be appealing names for new towns, it’s important to know that — at times — there’s a lot at stake in a name.

So any boost in land sales was forward momentum as far as the canal commission was concerned. This is where our recognizable Shakespeare characters, the towns named Romeo and Juliet, come in.

“I truly believe that it was almost an advertising gimmick,” Sandy Vasko says. She suspects “somebody who was big into advertising said: ‘Ya know, let’s do this. Let’s call this new land Romeo, it’ll be a catch thing and maybe we can sell a few extra lots because of the Romeo and Juliet connection.’”

Sound like a far-fetched connection? Well, consider that, when we kicked the British out of the colonies, we let Shakespeare stay. And in 1800s America, the works of Shakespeare reached a new form of American kingdom.

“Shakespeare is in the theaters, it’s in peoples rhetoric books. They’re being taught passages of Shakespeare and how to speak it in order to be eloquent,” says Heather Nathans, chair of the Department of Drama and Dance at Tufts University. “It had a kind of familiarity that I think maybe we don’t have now.”

With that level of popularity, it’s hardly a surprise that Shakespeare was deployed, like today’s Cake Boss, to entice people to buy stuff. Shakespeare became the Shakespeare brand.

“Slap Shakespeare on [a product] and it instantly seems more elegant or elevated, or it’s some clever tie-in that draws your attention to whatever it might be: little mints or cigarettes or playing cards.” Nathans says.

If Shakespeare had become an important branding technique in 1800s America, was it used by I&M Canal commissioners? Again, there are no surviving documents that lay this out, but the Bard as “brand” would have solved a problem the canal faced: Illinois sometimes seemed an uninviting place to prospective landbuyers.

“People really didn’t want to move here because they were worried: Are these Indians going to kill us?” Vasko says. “One of the things [the commissioners] had to do was be sure that people wanted to come here, and that the Indians were gone.”

Mainly, the commissioners encouraged Illinois to act on the federal Indian Removal Act signed into law by President Andrew Jackson on May 28, 1830.

After the exodus, land sales to white settlers increased. “Now they felt safe,” Vasko says.

Heather Nathans adds: “I can’t think of a better way to declare that that is the past and this is the future, by putting on some nice, recognizable Shakespeare names.”

It’s hard to prove, but perhaps the new Shakespearean town names signalled safety to prospective settlers and investors back East. Regardless, the town names of Romeo and Juliet only stuck around for about 15 years, until 1845.

The change came about after former President Martin Van Buren passed through Juliet while touring western states. Van Buren noticed the town name of Juliet was similar to the name of Mound Joliet. He encouraged the citizens to reconsider having a town named Juliet after a girl, (again, supposedly Campbell’s daughter) and instead call it Joliet, in honor of the renowned explorer.

“And they took [that] under consideration,” Vasko says. “In 1845 they indeed changed the name from Juliet to Joliet. But, they did refuse to add any extra t’s or e’s. So the word was Joliet, very plain and simple J-o-l-i-e-t.”

We don’t know whether they gave Romeo a heads up, or even if they bothered to send a postcard. And we don’t know how Romeo felt about it. But we know what they did: That same year, Romeo added -ville to its name, becoming Romeoville.

The myth lives on

Even without official records or documentation that answers why each place was originally named as it was, hints of Romeo and Juliet persist within their modern incarnations.

As you drive through Romeoville you’ll pass Juliet Ave. and Romeo Road, Romeo Cafe and Romeo Plaza. In Joliet, you’ll find Juliet’s Tavern — a nod to the city’s former name.

But where the Shakespeare theory resonates most is perhaps at the Romeoville Area Historical Society. We take Paul, our question-asker, and his wife, Kathy there to meet Nancy Hackett, president of the society and a Romeoville resident.

Hackett shows us around the place, and we eyeball some items that hint at the area’s slight hangup on its past self.

Hackett says, even outside of the historical society, she lets the Shakespeare connection play out in her everyday life. Among other demonstrations, she shows off a bumper sticker that reads “Wherefore art thou, Romeoville?”

“For so long Romeoville was that tiny little place,” she says. “When people ask me where it is I say ‘It’s north of Juliet’ … and then I correct it.”

Hackett may correct herself on the town names, but there’s one thing she won’t budge on: Shakespeare is the reason for them. She says she knows this because it’s in a book written by a woman named Mabel Hrpsha in 1967. Hrpsha was a member of the historical society and part of a long line of Romeoville residents who lived in the unincorporated part of town.

Hackett finds the specific page of Hrpsha’s book, and reads:

Romeo was one town proposed by the canal commissioners along the proposed canal. It was named after the Shakespearean hero and planned as a romantic twin sister and rival for Juliet, later Joliet.

And even when she learns about the other two theories laid out in history books that predate Hrpsha’s, Hackett says: “I’ll stick with Romeo and Juliet.”

What’s in a name?

Without the evidence to confirm any single theory, it’s hard to disabuse people like Hackett who have chosen to take one theory or another as gospel. But maybe the tendency to perpetuate origin stories — and the many ways they manifest — can sometimes be more interesting than a verifiably true story.

At least that’s Callary’s take on our answer to Paul Kaiser’s question.

We learn that, through names, people make statements about their heritage. And if a tiny, tiny town like Romeo — almost written out of history books — has anything at stake, it is identity.

“Very few [people] have heard of Romeoville” Callary says. “Joliet is large enough to have an identity on its own but Romeo — or, Romeoville — might need a little bit of help.”

So people fill in the gaps because, well, that’s just what people do.

“It’s satisfying to have an answer,” he says. “And when we don’t … by golly, we make one up.”

Paul Kaiser, a retired math and computer science professor, moved to Joliet from Cleveland, Ohio, in 1973. As a curious new resident to the area, Paul got interested in the history of the I&M Canal. It was while he was learning about the canal that he first came across old maps bearing the town names Romeo and Juliet.

“For me this has been a trip around in a big, long historical circle,” Paul says. “It seems like we’re always coming back to the canal, its importance back in the 1800s for opening up commerce and developing communities.”

Luckily, Paul is comfortable with a bit of ambiguity in this Curious City investigation.

“I do like the theory of Juliet being the original name because of Campbell’s daughter,” he says. “But as the author says, we don’t have any records to really say with 100 percent accuracy. So it’s a good guess. I like the story. I’m comfortable with the story. But it still leaves some freedom to play with it if you want. I mean, it leaves mystery in your life.”

Katie Klocksin is an independent radio producer. Follow her on Twitter @katieklocksin. Logan Jaffe is Curious City’s multimedia producer. Follow her @loganjaffe.