Chicago Bathhouses: More Than A Century Of Sanitation, Sex and Sweat

By Miles Bryan

Chicago Bathhouses: More Than A Century Of Sanitation, Sex and Sweat

By Miles BryanAnna Erickson likes to walk around her Chicago neighborhood of Pilsen. A social studies teacher and history enthusiast, she says she can’t help but notice this odd brick building she often passes; it sits right in the middle of a residential block, and it has large Roman-style stone columns. Above the door, an inscription reads “Chicago Public Bath,” yet there’s no bathhouse running in there these days. (In fact, it’s zoned to become residential someday.)

Anna’s passed that building so many times that she eventually asked Curious City to figure out something that regularly gnaws at her: “There’s a public bathhouse in my neighborhood. What happened to the other bathhouses?”

You may have had a similiar question if you’ve ever passed one of these old facades or even the occasional operating bathhouse in the city. But defining Chicago’s experience with “bathhouses” is complicated. The word’s applied to different kinds of places, ranging from a place for the poor to scrub down; a place to have sex but then catch a show; and a place to pamper yourself with extreme heat and cold you would never tolerate anywhere else, let alone pay for the privilege.

We’re gonna cover all of these — don’t forget your towel.

Public bathhouses: Sanitation and civility

Let’s start with the kind of bathhouse Anna noticed in Pilsen. Spoiler alert: These are now extinct in Chicago, except for facades here and there.

The particular building that prompted Anna’s question is the “Simon Baruch” public bathhouse, named after the noted public health advocate and leader of the public bath movement in the United States. The city built the bathhouse in 1910 so that neighborhood residents could get clean.

“In a lot of the poor neighborhoods, they didn’t have indoor plumbing. So they didn’t have any bathing facilities,” says Maureen Flanigan, a historian emeritus at the Illinois Institute of Technology, adding that the experience was no luxury. “It was timed. … You got in, you got your soap, you got your towel and then you were out.”

As the Chicago Department of Health noted in its 1904-1905 biennial report, “These baths have not been established as places of diversion and pleasure, but to promote habits of personal cleanliness.”

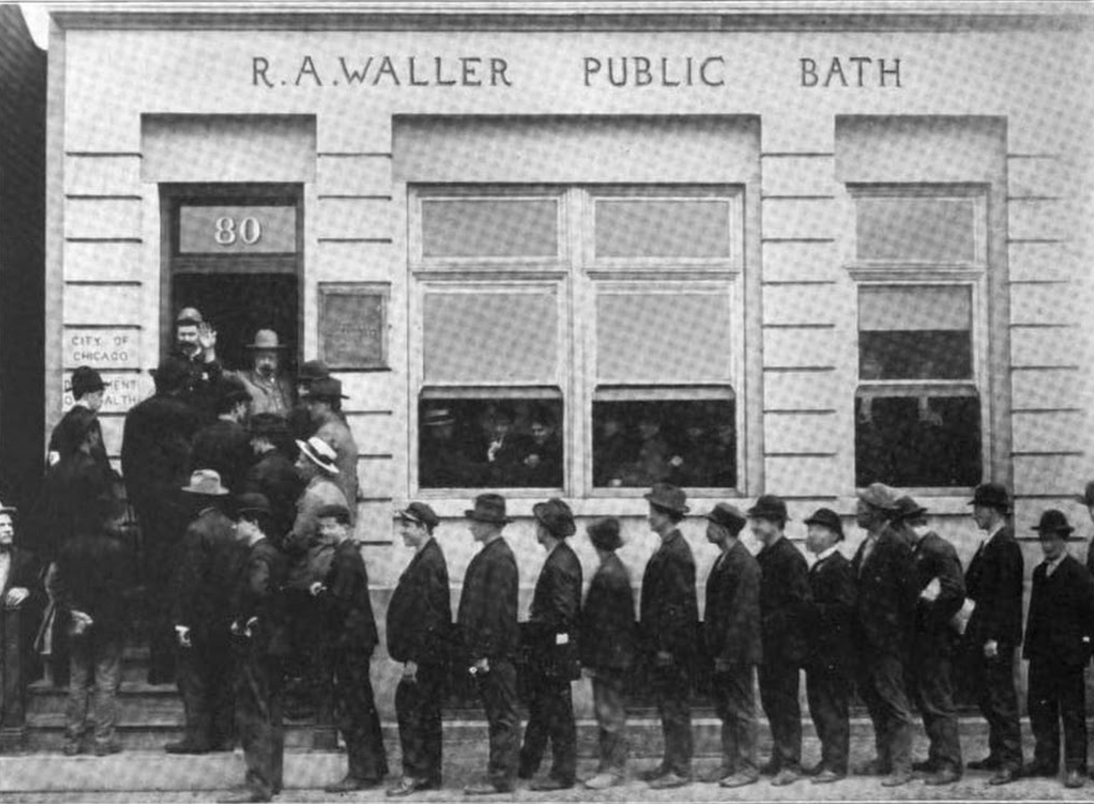

In 1893 just three percent of families living in Chicago’s ‘slum districts’ were in housing with bathrooms, according to Marilyn Thornton William’s Washing “the Great Unwashed:” Public Baths in Urban America 1840-1920. In 1894, the city built the first public bathhouse on the West Side.

By 1920, another 20 bathhouses were opened across Chicago, in neighborhoods ranging from Little Sicily to Bridgeport. According to Williams, they were in slum neighborhoods or industrial areas. Bathhouse facilities were co-ed, but they would be reserved for women and girls on certain days of the week, Flanigan says.

Chicago’s public bathhouses were funded and operated by the city, but they were opened because of a campaign by a group of female urban reformers who were known as the “Free Bath and Sanitary League.” Many women involved in this group were doctors, Williams writes. But their bathhouse advocacy was not just for health reasons; they believed that cleanliness was a sign of good moral character. As bathhouse advocate Dr. Gertrude Gail Wellington argued in a letter to Chicago’s then-mayor, the public bath “will inspire sweeter manners and a better observance of the law.”

But bathhouse advocates did recognize that washing was important for good health and that the poor had little access to clean water for bathing. As Flanigan explains, the germ theory of disease was gaining acceptance, and the middle-class and wealthy areas were getting indoor plumbing. “There was now more of a sense that the city should provide for everyone to have that, and if they weren’t going to have indoor plumbing they [the local government] had to provide these bathhouses for [poor] people.”

According to Williams, bathhouse attendance peaked in 1910, when more than one million baths were taken. Bathhouse construction continued until 1918, but by that year attendance had declined to about 700,000 visits. After World War II, Chicago gradually converted its public bathhouses into swimming pools or other facilities or closed and sold the rest. The last public bathhouse served residents of what used to be called Chicago’s Skid Row, in what is now known as the West Loop. It closed in 1979.

Gay bathhouses: Sex and socializing

As the public bathhouses had almost completely disappeared, a different kind of bathhouse had become central to Chicago’s gay male community.

In 1961 Illinois became the first state in the nation to repeal its anti-sodomy laws. This opened the door for openly gay bathhouses to set up shop for the first time, although gay men had already been frequenting some bathhouses for several decades.

In The Leatherman: The Legend of Chuck Renslow, historian and journalist Tracy Baim identifies three bathhouses popular with gay men in Chicago in the 1950s. Each had operated underground until the laws were repealed.

Chicago gay pioneer Chuck Renslow opened “Steve’s Health Club,” his first gay bathhouse, shortly after the repeal of the sodomy laws, but according to Baim, intolerant police forced it to close a few months later. In 1970, Renslow opened Club Baths, this time as a ‘private club’ to avoid police hassle. Then, in 1973 Renslow opened Man’s Country, also as a private club. Now the city’s longest-running gay bathhouse, Man’s Country is a sprawling compound with two three-story buildings filled with private rooms, fetish areas, dance floors, a wet room, and a locker room.

Ron Ehemann, Renslow’s longtime life and business partner says, in its heyday, the bathhouse “provided a place where you could meet other men that were also looking for sex with other men. But it was so much more than that. The bathhouses and the bars … were the only social institutions that we had at that time.”

Ehemann says Man’s Country’s hit its peak in the 1970s and early 1980s, a period when it would feature entertainment four nights a week. “A lot of acts that were trying to break into the legit houses downtown would come here,” he says. “The Tribune and the Sun-Times would come here to see an act and review it, and [then] they would get jobs elsewhere.”

Ehemann says gay bathhouses, including Man’s Country, began to decline with the arrival of HIV/AIDS in the mid-1980s. Ehemann says income dropped 80 percent within just a few years. He says the vibe also changed.

“People who were coming in [post HIV/AIDS] were only coming in for sex,” he says. “They weren’t coming for a party, they weren’t dancing. The people who were coming just to socialize tended not to come anymore.”

Chuck Renslow died this year at the age of 87. Ehemann says Man’s Country will likely close by year’s end.

Ehemann is bullish about the future of gay bathhouses in Chicago as a business — but mostly as sex and dance clubs; he says the community’s desire for social and civic space now lives on in LGBT organizations like the Center on Halsted.

“You can live anywhere and fly your rainbow flag on the front of your condo and your neighbors aren’t going to care. The notion that you have to have specific places like baths and bars to hang out in — that’s just changed,” Ehemann says.

Note: If viewing on mobile, video will not work unless viewed through the YouTube app.

Private bathhouses: Sweat and relaxation

Chicago’s public bathhouses are closed, and its gay bathhouses are far less popular than they once were, but private Russian- or Korean-style bathhouses that focus on relaxation are booming.

The city’s tradition of Eastern European style bathhouses goes back more than a century. Many of the original operations are long gone; the “North Avenue Baths” building, a private bathhouse built in 1921, now houses a restaurant and private apartments. However, there are several immigrant-run bathhouses still offering Chicagoans a place to sweat and relax.

Two popular Russian-style bathhouses in Chicago are the Chicago Sweatlodge in Portage Park and Red Square Spa on Damen Avenue and Division Street. Chicago Sweatlodge is the newcomer, having opened in 2007. Red Square Spa has operated in it its original building since 1906, though in different forms and with different owners.

Fans of Chicago literature would rightly guess that Red Square was featured in Saul Bellow’s 1975 novel Humboldt’s Gift, where he wrote that patrons are cast in “antique form.”

“They have swelling buttocks and fatty breasts as yellow as buttermilk. They stand on thick pillar legs affected with a sort of creeping verdigris or blue-cheese mottling of the ankles. After steaming, these old fellows eat enormous snacks of bread and salt herring or large ovals of salami and dripping skirt-steak and they drink schnapps. They could knock down walls with their hard stout old-fashioned bellies. Things are very elementary here. You feel that these people are almost conscious of obsolescence, of a line of evolution abandoned by nature and culture. So down in the superheated sub cellars all these Slavonic cavemen and wood demons with hanging laps of fat and legs of stone and lichen boil themselves and splash ice water on their heads by the bucket.”

It’s still possible to steam and eat at Red Square today. Alex Loyfman bought Red Square, along with several partners, in 2011. He renovated the building and added a women’s side. Loyfman says his clientele is still “30 to 40 percent” Eastern European. But the majority are young people from the neighborhood, he says, and others who just find the sauna relaxing. Loyfman says Red Square is popular with politicians and celebrities, too. “Jesse Jackson is here from time to time,” he says.

Red Square’s narrow, three-story building has a traditional Russian-style restaurant on its main floor. It’s lined in dark wood paneling, and projections of a train trip through Russia play on the walls.

Separate staircases go down into the men’s and women’s side of the facility. Each leads to a maze of changing rooms, showers, a wet sauna, steam room, and a hot tub. The men’s side also has a cold pool. Men and women share a dry sauna.

Another co-owner of Red Square, Maris Glukhova, says that business for the bathhouse was up 20 percent over the last year.

Russians aren’t the only ethnic group with a sauna tradition that survives in Chicago. Two Korean-style bathhouses are open in the area: Paradise Spa in the city’s Albany Park neighborhood and King Spa in suburban Niles. Curious City was unable to reach an owner or manager of Paradise Spa, but Jin Lee, a leader in Chicago’s Korean-American community and a Director of Government Relations and Business Planning and Development at the Albany Park Community Center, says it’s been open since at least the “late ‘80s or early ‘90s.”

King Spa, which opened in 2010, is now the preferred choice for Korean-Americans in Chicago, Lee says. King Spa has a large restaurant and sauna complex, and it’s open 24 hours a day. It offers hot tubs, a steam room, and a cold pool, as well as massage and other spa services.

Although these bathhouses charge a fee (it costs $35 for a day at Red Square and at King’s Spa), Loyfman of Red Square says part of what keeps people coming to the bathhouse is that it’s open to everyone. He believes the sauna is truly a “democratic experience.”

“All people, all walks of life — everybody’s talking. This guy could be a doctor, a lawyer. This guy is a plumber, everyone is communicating. It really brings a different kind of communication than we are ordinarily used to, you know,” he says. “They are naked in front of you!”

More about our questioner

A social studies teacher, Anna Erickson lives in Chicago’s Pilsen and likes to take walks at night (often while listening to podcasts). One of the walks was responsible for her brush with the Simon Baruch Chicago Public bathhouse — the inspiration behind her Curious City question. She’s been on a reporting trip there with historian Maureen Flanigan and Curious City, and has gotten up to speed on the history of public and private bathhouses in the city. Now, she says, thinking about the different bathhouses together — as a group — makes sense.

“Yeah they were all called ‘bathhouse’, but they were all serving a purpose in the community. Whether it was, early on, actually being a place to clean yourself. Whether it was a social gathering in the gay community when you didn’t have a lot of options … it was just filling a need in each of these communities.”

A parting note: Anna says she intends to check out Red Square sometime soon.