Chicago’s Tornado-Proof Delusion

Yes, tornadoes can hit Chicago. Why do so many people think otherwise?

By Chloe Prasinos

Chicago’s Tornado-Proof Delusion

Yes, tornadoes can hit Chicago. Why do so many people think otherwise?

By Chloe PrasinosCurious Citizen Erin English Bailey had a healthy fear of tornadoes as a kid. She grew up near the northwestern limits of Chicago-area sprawl and she remembers when the tornado siren would go off.

“There were plenty of times when I was in the basement with my brother, waiting for the sirens to stop,” she says. Together, they’d sit there, huddled in the basement, and Erin’s imagination would get away from her: “I was afraid of cars flying through the air and our house blowing out, our roof blowing off.”

Years later, Erin moved to Chicago proper and she noticed something odd. “Suddenly, people were just like, ‘Whatever.’ They were just really blasé about it and like ‘That’s not gonna happen here.’” She heard it enough that she passed her observation to Curious City, asking:

Why do they think that? And has a tornado ever hit Chicago?

Erin never placed much stock in many Chicagoans’ assumption that tornadoes can’t happen within the city. She thought weather patterns are weather patterns, and they shouldn’t have anything to do with how many people do or don’t live in a particular area.

Well, we have some answers in hand when it comes to the myths associated with Chicago and tornadoes, but let’s start with the most pressing question first.

Can a tornado hit Chicago?

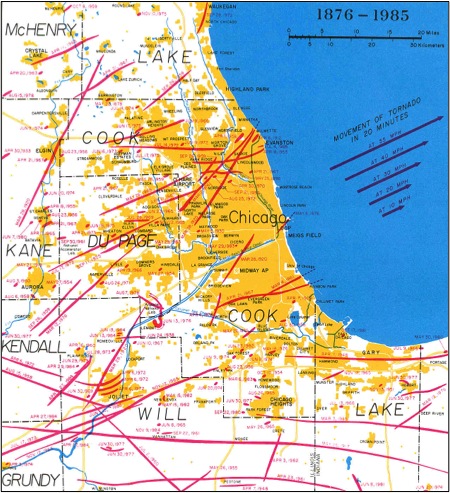

The answer is simple: Yes. A quick perusal of this map shows paths of tornadoes across the region. An even closer look shows several twisters moved within the city limits and throughout inner-ring suburbs.

If a historical timeline and a map are not enough to answer the question, consider first-person accounts. Here’s just one example. On April 21, 1967, a tornado hit the south side of Chicago. It tore across the Dan Ryan Expressway during rush hour, tipped a tractor-trailer, and then spun out over Lake Michigan. That storm is known as the Oak Lawn Tornado, named for the village that bore the brunt of that storm’s devastation. And that village is not a far-flung suburb. It’s right on the city’s southwestern border, sandwiched between the neighborhood of Beverly and Midway airport. In Oak Lawn, the memory of that tornado is still very alive.

Patti Kolb Ernst, Jodi Marneris, and Bob Philbin survived the Oak Lawn Tornado of 1967. Credits and contributions.

To this day, people in Oak Lawn say that the tornado of 1967 is the defining moment in the village’s history. And remember, Oak Lawn is literally next door to the city. This storm was the deadliest tornado ever to hit the Chicago area — 33 people were killed that day, 500 were injured. There was at least $40 million in damages in 1967 which, adjusted for inflation, would amount to more than $250 million today.

Why do people think a tornado won’t hit Chicago?

To answer this portion of Erin’s question, we tapped Dr. Victor Gensini, who happens to wear many hats. Among other things, he’s a meteorologist, a storm chaser, and an associate professor at the College of DuPage. Gensini is a good pick, as he’s familiar with the urban legends involving Chicago and storms. “About half of all incoming students in my meteorology classes think it is impossible for a tornado to hit downtown Chicago,” hesays.

As for which particular myths to bust? I repeatedly came across three myths during my research, and I pitched them to Gensini on stage at a recent Curious City live show (appropriately themed: Chicago disasters). His responses below are taken from his live appearance.

Prasinos: Myth #1: Lake Michigan protects us by acting as a bubble or shield.

Gensini: That’s a scary one. Because it actually does in the early spring. … In March and April, the lake is cold enough to have a deterrent effect [that] actually mitigate[s] the chance of tornadoes. Now, once you get into May and June, that lake breeze comes in on the shore and actually enhances the tornado threat in many cases. So you don’t want to believe that the lake is an absolute protective mechanism against tornadoes, because it’s actually not at all.

Prasinos: Myth #2: Tall buildings create some kind of buffer because they’re so tall and close together.

Gensini: So, the building argument is an interesting one. If you look back in history to large cities that have been hit by tornadoes, their buildings actually cause worse damage. The wind is accelerated through the urban canyons. … If you were in a building, it would be one of the worst places to be, because you’d be in the tornado with the glass breaking. It would be a very, very bad thing. [Buildings] are absolutely not mechanisms to protect you or stop a tornado.

Let me just say: A tornado doesn’t care what it’s hitting.

Prasinos: Myth #3: The third myth has its own name — the urban heat island effect. Would you explain what that is?

Gensini: So all of the pavement that we have around Chicago has something that has an albedo (not a libido ok). … The albedo of Chicago is the fact that the incoming sunlight actually absorbs all the energy and sort of holds on to it and creates a temperature anomaly over the city. And some people think that there’s this heat bubble over Chicago that would somehow stop these storms as they come in. And, … in our modeling studies, [the heat] would actually increase the intensity of the storms, not decrease. So the urban heat island effect is definitely busted.

Prasinos: Alright so none of those myths offer us any kind of protection. How likely is it that a bad tornado will hit downtown Chicago?

Gensini: These are extremely low probability events. They’re very small scale. People think of tornadoes as these big things, but in the atmosphere they’re very, very small. And their paths of damage are often only a couple yards wide. And they only last maybe 10 to 20 minutes, if you’re lucky. So these are very low probability events.

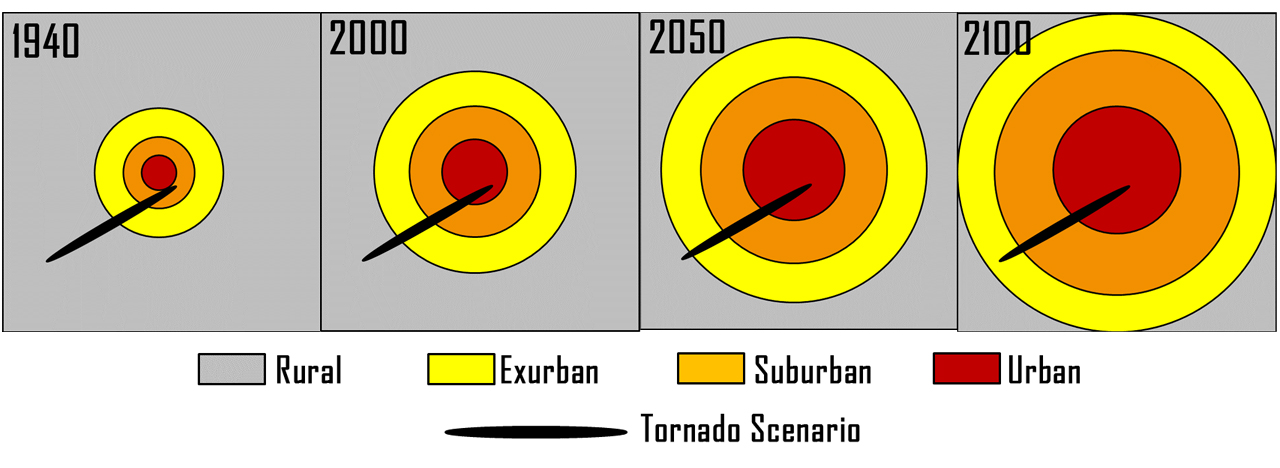

If you think of a dartboard … These tornado events, you’re kind of just closing your eyes and throwing them at a dartboard. And the city center would be [the bullseye of] Chicago.

(Research credit: Strader and Ashley 2015)

So in 1940, the size of Chicago would be a relatively small bullseye on the dartboard. And as we go through time we of course have urban sprawl, especially on the western fringes. And by 2000, of course, the city grows larger. Extrapolate that into the future: Now we have 2050, now the bullseye is getting larger, of course, mainly on the western edges. …

And then if we extrapolate this out to 2100, you’re closing your eyes and you’re throwing that dart, which is that black tornado path [in the graphic], at a much larger bullseye. …

The Plainfield Tornado in 1990 was an interesting case. … Plainfield’s population in 1990 was about 5,000 people. … The population now is about five times larger than that. And we had a close call last year. … The Fairdale tornado out by Rochelle. Not to mention, there are people in rush hour stuck on the expressways. This has long been one of my greatest fears — a significant or violent tornado moving through Chicago during rush hour. And it’s a serious thing that we have to think about. It’s a low-probability event, but it can happen. And if you think of the three largest cities (New York, Los Angeles and Chicago) Chicago by far has the highest risk or probability for a tornado event. So we could easily say that Chicago is the most vulnerable city in the world to tornadoes.

Prasinos: Speculate for me: Why does the myth that a tornado won’t hit our city persist if it so clearly has hit the Chicagoland region?

Gensini: It comes back to complacency. Complacency is the feeling that something can’t happen to you. And these events are extremely rare and we have to face that … they’re not things that happen every week or every month or even every year. And you’re lucky sometimes, in terms of probability, to get them once every 10 years, or sometimes 50 years.

It’s a very difficult problem, you’re trying to forecast something that’s very small, short lived. … But they didn’t happen to you. And until they [do] happen to you, you don’t realize, you don’t hear these stories, until it [does] happen to you and you create that story.

(Note: Just last year Chicago had a close call with a tornado. So we’re taking the opportunity to tell you: Take heed! A preparedness brochure from the city of Chicago should help. It tells you what to do and where to go various environments. And remember: Stay away from windows!)

Curious Citizen: Erin English Bailey

Erin English Bailey is a non-profit arts administrator and the mother of two small children. When she first moved to Chicago from the northwest suburbs, she was dubious of the myths she heard kicking around that the city was somehow immune from tornadoes. But now, after hearing we dispelled some of those, she says: “I feel somewhat vindicated to learn that tornadoes can and have happened in Chicago.”

But she worries that even after Chicagoans hear this story, they’ll slowly forget about the threat of tornadoes yet again.

“I do wonder, however, if even having proof from living participants or the testimony of a meteorologist would actually persuade Chicago residents to duck and cover when a tornado is on its way,” she says.“I hope we don’t have to find out.”

Meteorologist and Storm Chaser: Victor Gensini

Dr. Victor Gensini is an Associate Professor of Meteorology at the College of DuPage and an atmospheric scientist with research interests in applied climatology, GIS techniques, operational and synoptic meteorology and severe convective storms. He got interested in severe weather on April 20, 2004, when a tornado passed a mere 100 yards north of his high school. After seeing the damage from the tornado, Dr. Gensini never looked back on a career in meteorology. He now takes students into the field to study severe weather and continues to work on research advancing the field of severe storms meteorology.

Gensini is pushing the tornado prediction envelope. According to his research, Gensini claims to have developed a way to predict the likelihood of tornadoes two or three weeks in advance. And so far, he’s been pretty spot on. In 2015, he made predictions for tornado activity in the United States at large. He was right 10 out of 15 times.

Additional research references found in work published in the journal Weather, Climate and Society, conducted by Walker S. Ashley, Stephen Strader, et al.

Chloe Prasinos is a freelance reporter and producer. Follow her @chloeprasinos and check out her work at www.chloeprasinos.com.