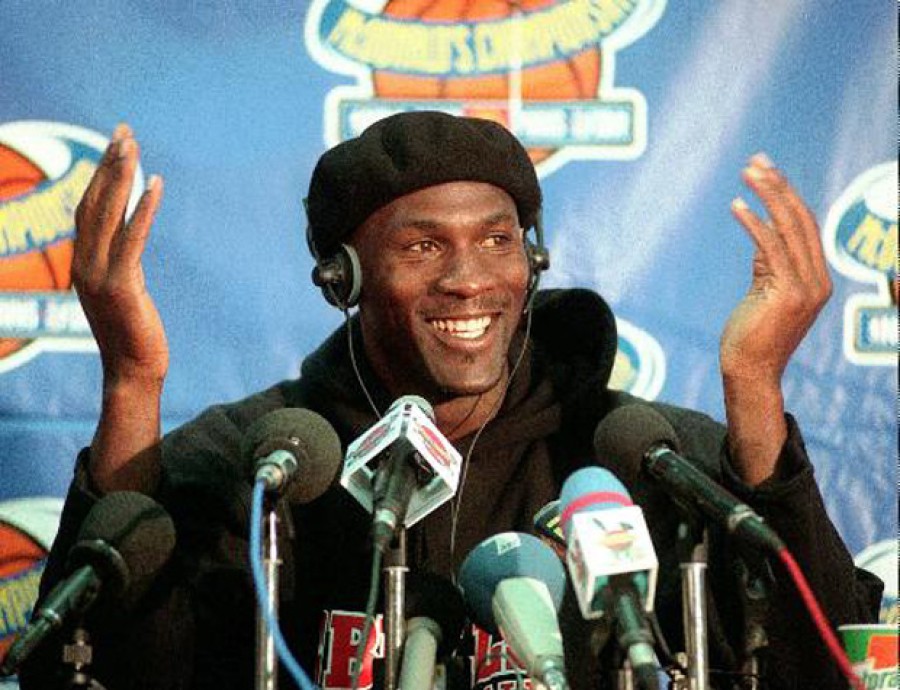

Everyone from superfans to the casual office bracket pool participant follows NCAA March Madness. We rally around underdogs. We’re suckers for Cinderella stories. It’s as much about these journeys as the sport itself. So as teams compete for the championship title, let’s look at Chicago’s biggest basketball legend. Our tall tale. Michael Jordan.

Jordan came to Chicago in the 1980s, and went on to have one of the most memorable careers in basketball. Briefly, Chicago had the best sports team in the country. We were known around the world as the home of Michael Jordan and the Bulls. He brought home six NBA championship trophies in the ‘90s.

Jordan’s lasting fame in Chicago is what prompted a seventh-grader working on a history project to ask this question about him. (The student chose to remain anonymous.)

What was Michael Jordan’s impact on Chicago?

Jordan wondered about his local legacy too. In 1993, he said this to a crowd at the opening of the Michael Jordan Restaurant:

“I want to say to the Chicago people, thank you for your support. Ever since I came to this city in 1984, you have taken me in like one of your own, and I’ve tried to reciprocate that in my talents and playing the game of basketball. Hopefully the two is going to be a relationship that’s going to last a lot longer than me just playing basketball.”

MJ did indeed leave the Bulls and the city in 1999. So, what did MJ leave behind? We consider possible economic impacts as well as his cultural — even spiritual — contributions, too.

Timeline: A brief history of Jordan

If you’ve never been a Jordan fan, just need a refresher, or are too young to remember, here’s a timeline of how Jordan’s career intersects with Chicago history.

Jordan’s economic impact: A windfall for the Windy City?

In the 1990s, the Bulls were on fire. They won championships. More people bought tickets to games and wanted Bulls memorabilia. However, according to sports economists we talked to, it’s difficult to find measurable economic impact on the city.

Allen Sanderson, an economics professor at the University of Chicago and editorial board member of the Journal for Sports Economics, says pro sports teams typically draw in-person audiences within a 25-mile radius. He argues that when all those Chicagoans and suburbanites bought tickets to basketball games, that very same ticket cash likely would have just gone elsewhere — say, to Chicago restaurants, malls, etc.

Economics and Business Professor Rob Baade of Lake Forest University agrees that during Jordan’s time in Chicago, it was likely that local fans just shifted some of their spending from one entertainment choice to another. Bulls are on a hot streak? Spend Saturday night in the arena. Lackluster season? Go out to dinner instead.

These kinds of arguments, he says, continue beyond Chicago and Michael Jordan. Consider a more contemporary debate about economic influence and famous athletes: LeBron James and the city of Cleveland, Ohio. Sports celebrities have some effect, Baade says, but it’s often modest.

“If you make the argument that Cleveland’s economy has ramped up during LeBron’s return, you’d have to look at the entire Ohio economy,” he said.

Whatever modest effect Jordan did have, though, likely got a bump from the fact that he got the Bulls into the playoffs, effectively lengthening the local playing season, and creating several more games.

“You can make the argument that more people are coming in to watch playoffs. But that’s not lasting,” Baade said.

But what about Jordan’s own spending? After all, by the mid-90s he was one of the world’s highest-paid athletes.

Sanderson says the success didn’t put money back into Chicago because that money was spent elsewhere. Jordan went on trips to Jamaica and other places that took him — and his wallet — outside of the city.

Jordan does still have a home in north suburban Highland Park. The mansion, complete with entrance gates adorned with the number 23, is for sale. Though he left the city more than 10 years ago, the house is still on the market. (Any takers? There’s a gym and a basketball court (duh), and it’s only $16 million.)

What about the Michael Jordan Restaurant? It’s closed (possibly because of bad reviews such as this one), but the Michael Jordan Steak House, which opened in 2011, still stands. The restaurant employs about 150 people. According to manager Myron Markewycz, the operation’s doing well. Markewycz estimates that during the first few years it was open, Jordan visited the restaurant about 30 times. That was before Jordan divided his time between residences in Charlotte, North Carolina, and Florida. Now, while Markewycz can’t give a specific number, he says they see much less of Jordan.

The United Center: The house that Jordan built?

It’s tempting for an armchair historian to credit the United Center’s construction to Jordan and the Bulls’ success. After all, you can’t miss the statue of Jordan that dominates one of the center’s main entrances. And, a surface reading of the timeline lends some evidence: Jordan arrived in 1984 and the United Center opened for business in 1994, replacing the Chicago Stadium.

But actually, the United Center was a joint venture designed to house both the Bulls and the Blackhawks hockey team. And it was first planned in 1988, years before the Bulls’ first championship in 1991.

Sanderson says it’s likely Jordan was just in the right place at the right time. Yes, Jordan excelled at the United Center, but basketball’s popularity was the draw, not Jordan.

Jordan’s rookie season was 1984, just as the NBA’s popularity began to snowball. Until then, not many Americans watched basketball at the stadium or on TV. According to Sanderson, the playoffs were taped and aired later because not enough people wanted to watch them live. The sport gained momentum throughout the ‘80s. Jordan and the Bulls, he says, rode the wave.

Sam Smith, a sports reporter who covered Jordan for the Chicago Tribune and authored two books about the star, says this rising tide compelled the NBA to push all teams — including the Bulls — to build new stadiums, fill seats and boost revenue.

“They committed all of the franchises to have to get new buildings,” he said, adding that if teams couldn’t pull it off financially or politically, they were pressured to look for new cities to play in.

“Everybody was put onto this,” Smith said. “That’s why Seattle’s team moved to Oklahoma City, as an example.”

But Charles Johnson, the CEO of Johnson Consulting (a firm that works on stadium projects, among other things) gives Jordan more credit.

Johnson helped supervise the development of the United Center for Stein and Company. He says the previous venue, the Chicago Stadium, had become obsolete and that there “was no doubt” that the United Center would have been built at some point. Still, he says, Jordan “absolutely” drove the timing.

“I think it is safe to say that this is the building that Michael built,” he said. “I do not think this can be said anywhere else, so emphatically.”

Johnson, Sanderson and Smith agree that Jordan had a definite impact on the new stadium’s capacity and other amenities — in particular, the high number of suites.

“If MJ was not in the picture, that many suites would never have happened,” Johnson said, adding that the decision to create additional luxury seating turned into an excellent revenue stream for the construction project.

Smith goes further, saying that the NBA pointed to Jordan’s track record and crowd appeal as an argument to expand suites and other accommodations. He says the franchises listened.

“You can make a case with Michael that he influenced all of these buildings everywhere,” Smith said.

Charitable impact

Throughout the 1990s, Michael Jordan was the richest athlete in the world, raking in $78.3 million in 1997 alone. Even if Chicago felt little economic impact from the Bulls’ success, you might suspect that Jordan’s personal wealth — and fundraising in his name — had potential to leave a more measurable mark on the city.

In 1989 Jordan and his mother, Deloris, created the Michael Jordan Foundation, a Chicago-based charity that focused on improving education on a national scale. It had two offices and twelve people on staff. Student who participated in Jordan’s Education Club could earn a weekend trip to Chicago if their grades and school attendance improved.

But in 1996, seven years after the foundation’s start (and shortly after Jordan made his famous Bulls comeback), he pulled the plug. Jordan told the press he wanted to take a “more personal and less institutional” approach to financial giving, and that he’d rather “pick and choose to whom I give my donation.”

And, aside from a substantial $5 million donation to Chicago’s Hales Franciscan High School in 2007, Jordan doesn’t seem to have picked or chosen much else when it comes to local donations.

One Chicago charity to which MJ does still contribute is the James R. Jordan Foundation, an evolution of the Michael Jordan Foundation named in honor of his father. Deloris Jordan (Michael’s mother) is the founder. Michael has little administrative involvement, a fact quickly asserted by the foundation.

“He hasn’t been here in how many years?” said Samuel Bain, the foundation’s director of development. “[MJ] hasn’t lived here, hasn’t played here.”

Bain says it’s challenging to quantify the impact of the James R. Jordan Foundation on the city itself, but suspects it’s benefited more local children and families than MJ’s efforts in the early ‘90s.

Under Deloris’ direction, the James R. Jordan Foundation partners with three Chicago K-8 schools, two of which are on either side of the United Center. Every student enrolled in these schools is part of a program called the A-Team Scholars, which awards scholarship money to students based on the letter improvements of their grades each semester.

Bain says the program has helped Chicago kids make it to high school and college. Some students have become Gates Millennium Scholars, and a number of graduates from the James R. Jordan Schools have returned to Chicago as program mentors.

“The impact shows in actual neighborhoods, in kids who are making it,” Bain said. “It’s the result of making it to college.”

As far as MJ’s contributions?

“He’s a supporter like our other supporters,” Bain said. “We are not the Michael Jordan Foundation. We don’t want the focus to be on Michael.”

Second to none

Before MJ came along “if you were traveling and told someone you were from Chicago, people would say, ‘Oh, Chicago. Al Capone!’ Now, it’s ‘Chicago? Michael Jordan!” said Sanderson.

Sam Smith says that the city experienced a sense of pride that it hadn’t had before.

For a long time, he points out, Chicago was the “Second City” to New York or Los Angeles.

“Here in Chicago, sports teams have traditionally been unsuccessful. They were associated with losing and being made fun of,” he said.

That sentiment turned around. The United Center’s Michael Jordan statue, entitled “The Spirit” and completed in 1994, has these words emblazoned on it: “The best there ever was. The best there ever will be.” It was as if, when Jordan was playing for the Bulls in the ‘90s, everyone was proud to be from Chicago.

“You can’t be the best forever,” Smith said, “but for a while we were number one.”