The Cook County Forest Preserves — more than 69,000 acres of hearty forests, prairies, and swampy wetlands — lie scattered across the Chicago area. Cook County was the first county in Illinois to establish a forest preserve district.

During the summer, some of these forest preserves get more than 20,000 visitors a month — people like Curious Citizen Arnulfo Delgado. Arnulfo rides his bike through the preserves of Cook and nearby DuPage County several times a week.

“When you’re in touch with nature, you become aware of how life is so complex and at the same time very simple,” he says.

For Arnulfo, the most amazing thing about the preserves is the foresight it must have taken to create this vast escape from urban life.

But whose foresight was it? Arnulfo had no idea. So he asked Curious City: Who created the Cook County Forest Preserves?

The man who spearheaded the creation of the preserves was architect Dwight Perkins. His ambitious vision to preserve Chicago’s natural landscapes drew him into a 15-year battle that involved the courts, the Cook County Board of Commissioners, and even the governor. It wasn’t just a battle about whether the preserves should exist. Perkins also found himself fighting over what type of nature was worthy of protection and whether natural ecosystems should be left untouched or shaped by human intervention. The legacy of that fight lives on in the preserves today.

Dwight Perkins: an architect with a vision

Dwight Perkins grew up in Chicago during the late 19th century, a time when the country was just beginning to get nervous about its natural resources. Out west, the rugged American frontier had filled in with people. “There was also a lot of anxiety about deforestation,” says Natalie Bump Vena, an anthropologist at Queens College, and an expert on the Cook County Forest Preserves.

“In 1905, the US Forest Service was established,” Vena says, a sign that the government was increasingly aware of the problem.

Meanwhile, Chicago, once a lush expanse of prairie and wilderness, had morphed into one of America’s crowded urban centers, with a handful of parks the only hint of its bucolic past. Perkins took notice. As a teenager, he had worked in the stockyards, shuttling home each night to his working-class neighborhood on the near South Side. But young Perkins found an escape from grimy city life in the countryside. Perkins’ daughter, Eleanor Ellis Perkins, described his outings in Perkins of Chicago, a biography of her father:

“He spent many days in the marshes south of the city curiously trying to identify the course of the Calumet River that lay like intertwined strands of cooked spaghetti over the prairie lowlands at the foot of the lake. He watched wild ducks and migrating birds feeding and nesting in this bounteous refuge. … As a man later on he was able to formulate his conviction that human beings do not remain fully human if they are entirely cut off from the natural beauty of the world.”

So, when Dwight Perkins became chief architect for the Chicago Board of Education, his passion for the environment influenced his architecture. When he designed schools, he made plenty of room for playgrounds — which were revolutionary at the time — and placed the windows carefully, so that each student could see some glimpse of the sky outside, wrote Eleanor Ellis Perkins.

Perkins was close friends with some of the foremost progressive thinkers in Chicago, like social reformer Jane Addams, and landscape architect Jens Jensen. They would meet over snacks at Perkins’ house to discuss how they might improve the city, jokingly calling themselves “The Committee on the Universe.”

Around the turn of the century, the progressives grew concerned that the city’s population was growing faster than its outdoor spaces — and that working-class people had little opportunity to experience nature, says Chicago historian and preservationist Julia Bachrach.

“They felt that urban children needed access to these natural lands at the outskirts of the city,” Bachrach says. “So the vision for the Forest Preserves was [formed] with this pressing idea that the city keeps becoming more industrialized, and that these tenement people need to have access to nature.”

Perkins and his team develop a plan

In 1903, Perkins agreed to help the city’s Special Parks Commission explore ways to bring more nature into Cook County.

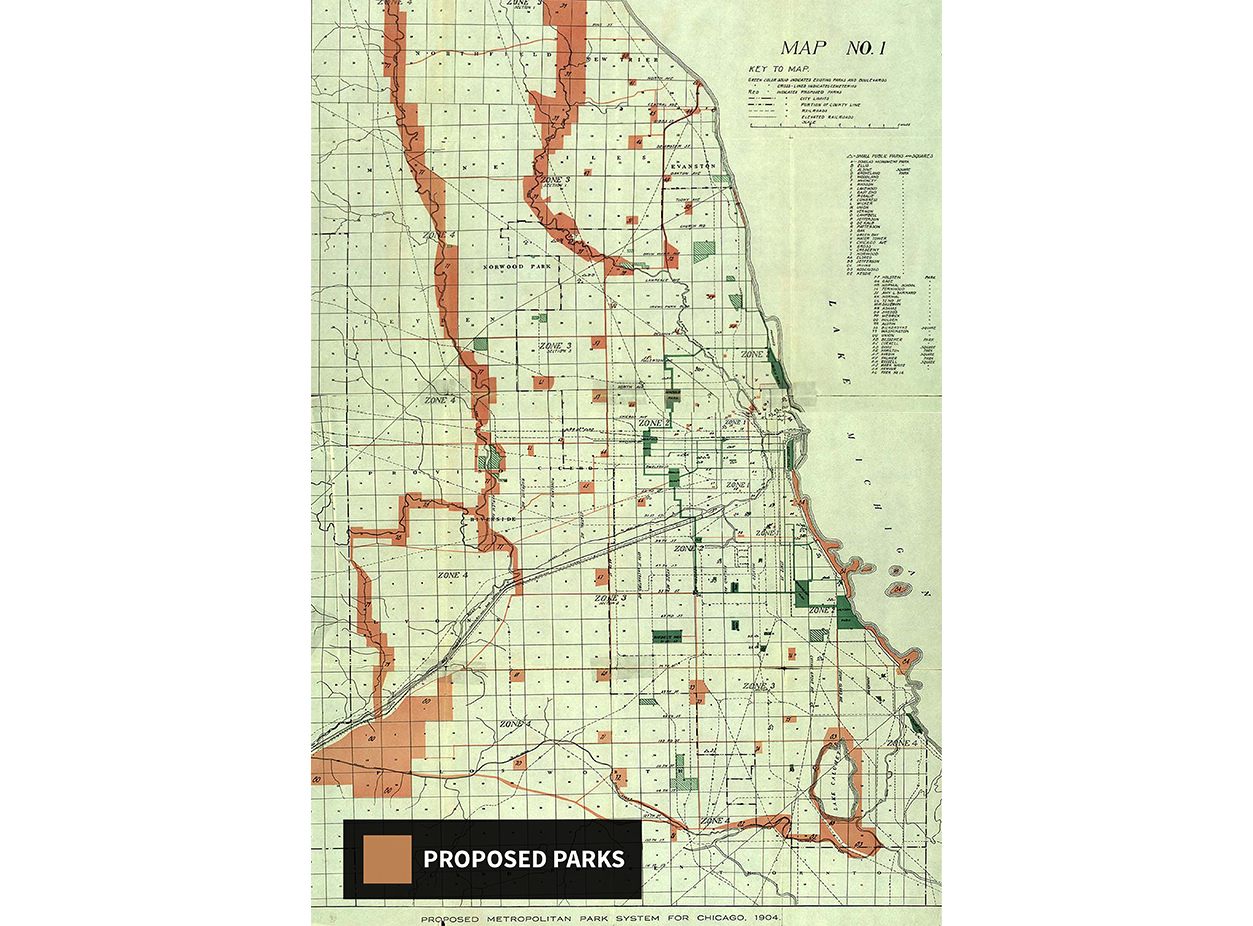

The next year, the commission issued a report that laid out, in exquisite detail, Perkins’ and Jensen’s vision for what would become the forest preserves. They said the county should create an “outer belt” of parks around the city, where people could go to experience nature. Jensen drew up maps recommending specific parcels of land, which included forests as well as wetlands and the flat grassy areas we now call prairies and savannas.

“The sweep of the report, the new concept of a city, the authority of its vision into the future brought tremendous excitement to those capable of understanding it,” Eleanor Ellis Perkins wrote in Perkins of Chicago. “Because the plan was right and did not compromise for the sake of expediency, it had power.”

But that plan would become entangled in years of conflict, as lawmakers struggled to determine what kind of nature should and should not be preserved.

The fight for the preserves

Perkins faced his first challenge soon after the commission released its report, when the president of the Cook County Board of Commissioners, Henry Foreman, decided to take matters into his own hands. Foreman quickly wrote a bill to establish this outer belt of parks, which he called “forest preserves” (the first time that term was officially used), says Vena.

It passed the state legislature — but Perkins didn’t like it. One major complaint, among many: Foreman’s plan focused on creating wide, manicured boulevards and roads, rather than serene nature preserves. This plan was a far cry from what Perkins and fellow commissioners had in mind, Vena says.

So, Perkins had to decide whether to let his vision be watered down, or fight for it, even though that could delay the creation of the preserves. Perkins chose to fight, and wrote a letter to the governor condemning the bill on legal grounds. The governor never implemented the bill.

“Dwight Perkins totally sabotaged this initial bill,” Vena says. “I guess it shows you a kind of unwillingness to compromise one’s vision.”

After that, politicians in Springfield began work on a new bill. This time, Perkins and Jensen wanted to make sure it was just what they wanted. They took the legislators and members of the public on daylong outings to see the natural beauties they were being asked to protect — including those they felt were under-appreciated.

“They really did think the prairie and the marshlands were beautiful,” Bachrach says. “And that’s where those Saturday afternoon walking tours became so important, because they’re helping people see this vision.”

They succeeded. This second bill passed in 1909. But it quickly became tangled in partisan politics. The bill went to court, and the whole thing was ruled unconstitutional.

“In the meantime land values had risen to five times what they were when Dwight wrote the report,” Eleanor Ellis Perkins wrote.

There was a comment in that court’s opinion that would spark decades of conflict over what kinds of nature deserved to be included in the preserves. Vena says a judge took issue with the “purpose clause” of the bill — the part that said what these “Forest Preserves” were supposed to do.

“The purpose clause had this really general language about preserving Cook County’s natural beauty and flora and fauna,” Vena says. “And the judge said, ‘Well, this could allow you to protect a prairie. But your district is called a ‘forest preserve,’ so you need to clean that up.’”

The judge was hinting at something critical: Not all nature was seen equally. People considered forests lush and romantic. But prairies? They were dry, and dull. Which was why when Perkins began work on yet another bill, he sensed he had to compromise, says Vena.

In the new bill, Perkins and a city lawyer specified that the district could only acquire land containing forests — even though they realized this might make it hard to acquire other kinds of land, like marshes or prairies.

“I think they did it because at this point they were desperate to push the legislation through,” Vena says. “Prices were going up, and they just thought, ‘We’ve got to do this before it becomes an impossibility.’”

The bill prevailed. In 1916, after 15 years of work on Perkins’ part, the Forest Preserves were finally a reality. The newly created Forest Preserve District began acquiring land.

The ongoing fight for Perkins’ vision

So, did Perkins’ vision ultimately suffer from this compromise?

In its early decades, the legal language restricted the kinds of land the Forest Preserve District could acquire. In 1927, the owners of the Skokie Marsh blocked the district’s attempt to buy their land. They argued that since there were no trees, it wasn’t a forest.

“I think at that point a lot of people equated nature with forests,” Vena says. “And that ended up having a huge impact on land management in the Forest Preserves for most of the 20th century.”

Even after legislators amended the language to make it easier to acquire treeless land, the Forest Preserve District still tended to favor forests over other landscapes. For instance, in 1930 alone, the district planted 126,309 trees on forest preserve properties. For decades, workers mowed over grasslands, and suppressed the natural fires that prairies needed to survive. By the 1970s, prairies and savannas were on the verge of disappearing from Cook County.

That’s when activists like Stephen Packard began to take action.

Packard has led an initiative to restore endangered ecosystems in Cook County since 1977. His work on prairies has received the most attention, since it required cutting down lots of trees and regularly setting fire to the land.

That has been a source of controversy. Starting in the 1990s, conservation groups in several neighborhoods organized to oppose Packard’s work. They saw Packard as a nuisance who was destroying the forests that people enjoyed, just to cover them in tall prairie grass.

These concerns led the Cook County Board to order a moratorium on all restoration in 1996. But it was short lived — the restorationists eventually convinced preserve leaders that their actions were needed to save the prairies and other endangered landscapes from extinction. Today, you can still find Packard and his crew planting seeds and burning brush out in the preserves.

Packard says it’s not about prioritizing prairies over forests. Rather, it’s about saving those ecosystems most at risk of vanishing — just as Perkins himself had hoped to do.

“I have every confidence that Dwight Perkins and all the people who were involved in the early thinking about the Forest Preserve would say ‘thank you’ to today’s volunteers,” Packard says.

More about our questioner

On a sunny September morning, Arnulfo and I met up with anthropologist Natalie Bump Vena at Deer Grove Forest Preserve in Palatine. As we talked, the three of us walked along a lake with ducks splashing around, beneath leaves just starting to hue orange.

So what about Dwight Perkins’ story most resonates with Arnulfo? “That grandiosity of spirit to think ahead,” he says.

After listening to Vena, Arnulfo was struck that Perkins had the foresight to care not only about the land itself, but its impact on the future generations of Chicagoans. Arnulfo works as a pediatrician in Little Village, and he says that kids growing up in the city today need the serenity that the forest preserves offer more than ever.

“I think that would relieve a lot of tension in the blighted areas that are suffering from a lot of violence,” he says.

Jake Smith writes and reports in Chicago. Follow him at jakejsmith.com and on Twitter at @JakeJeromeSmith.