In search of Chicago’s abandoned cable car tunnels

By Robin Amer

In search of Chicago’s abandoned cable car tunnels

By Robin Amer

I’ve been spending a lot of time underground the past few weeks.

Like, literally. I’ve been trying to answer a question Rogers Park resident Karri DeSelm submitted to Curious City:

I have heard there is a network of layered tunnels under the city. Is this true, and if so, what was the purpose of the tunnels when they were designed and built?

Next week I’ll have a full answer for Karri, exploring what turns out to be the many different kinds of tunnels hidden under Chicago’s downtown.

In the meantime, here’s a kind of preview: a look at one particular set of historic tunnels – and a search for what’s left of them.

The past

You may not know it, but before Chicago had the “L” the city ran on cable cars. In fact, Chicago was once home to the world’s largest and most profitable network of cable cars.

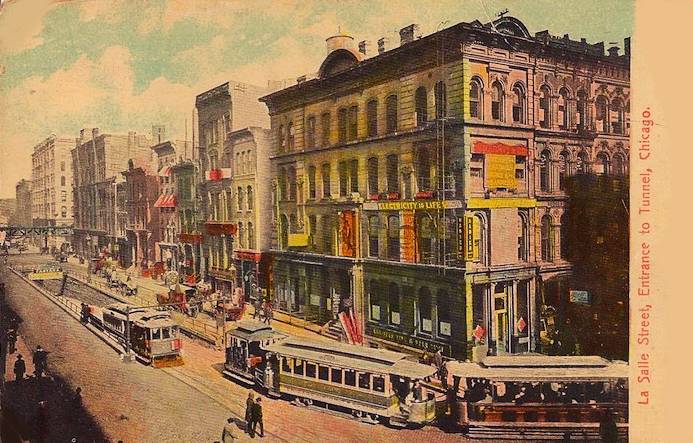

And, just as city planners built bridges to take traffic of all kinds over the Chicago River, they also built tunnels under the river, first for pedestrians and wagon traffic and later for street cars.

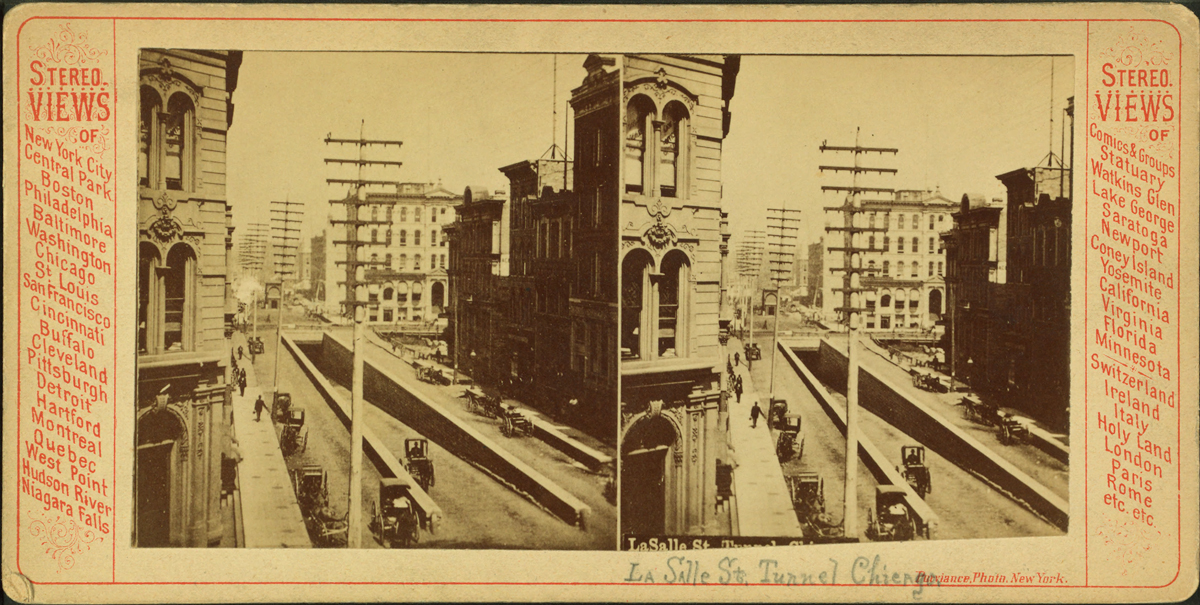

So the city dug two tunnels to alleviate traffic, one under the river at Washington Street that opened in 1869, and another at LaSalle Street that opened on July 4, 1871. An illustration of the LaSalle Street tunnel from an 1877 guidebook depicts a series of three brick-lined archways: two one-way passages for wagon traffic and a third for pedestrian use. According to Carl Smith, one reporter noted the following about the LaSalle Street tunnel on the day of its grand opening:

It was “well lighted with gas, and admirably ventilated, and as neat, clean, and free from dampness as could be desired. In all respects it seemed to be a model tunnel,” especially when compared to the damp and “unpleasant” Washington Street Tunnel…

One speaker noted that the choice of Independence Day for the opening was especially fitting, “since the completion of the tunnel was the beginning of an era of independence from bridge-tenders, railway companies, and lazy lake captains.”

When cable cars and then street cars came to Chicago in 1882, the tunnels had to be dug deeper underground. “They were very shallow,” says CTA transit historian Bruce Moffat. “As ships got bigger they started worried about hulls of ships running into them.”

The refurbished tunnels were approximately 60 feet underground, as deep as the deepest portions of today’s CTA tunnels. But their entryways were much steeper: they rose and fell at a 12 percent grade, according to Moffat.

“The steepest grade or ramp an ‘L’ train has now is in the order of four percent,” Moffat said. “So they had to be going actually at a pretty good clip at the bottom.”

The West Chicago Street Railroad, a private cable car company, dug a third tunnel under the Chicago River between Van Buren and Jackson Streets in 1894. But as the city moved on from cable cars to electric streetcars, and from electric street cars to elevated trains (and diesel busses and cars), the older means of transit faded away and the companies that ran them gradually went out of business.

All three cable and streetcar tunnels were eventually shut down and sealed off, and Moffat says they are not incorporated into existing CTA infrastructure.

“They’ve long since been decked over at both ends,” he said.

The present

But during my conversation with Bruce Moffat, he left me with this one tantalizing tidbit: “If you go to the corner of LaSalle and Kinzie,” he said, “you’ll find a manhole cover that leads down into the tunnels.”

Really? That sounded like a dare to me.

I called up my go-to guys for checking out historic urban remnants: Dan Pogorzelski, Jacob Kaplan and Patrick Steffes. They run the website Forgotten Chicago, which chronicles strange and delightful bits of the city’s built ephemera. They also offer walking and biking tours, such as their upcoming bike tour of Chicago’s Avondale neighborhood.

I convinced Dan, Jacob and Patrick to help me look for signs of the old tunnels —and, if possible, to help me find a way inside.

We met up at the corner of LaSalle and Kinzie on a Saturday morning, in search of Moffat’s manhole cover. But a cursory look reveals that this particular intersection is lousy with manhole covers, most stamped with the names of various utility companies.

We skulk around for a while counting. Finally Patrick returns with a tally, an astonishing 57 manhole covers.

“Counting side streets but not counting square covers or storm sewers,” Patrick says.

Dan asks whether this might merit an honorary street sign.

“This would be at the point where the tunnel would be coming in,” Dan said, peering down, and reminding us that the tunnel’s termination point was actually closer to Hubbard Street.

He wriggled onto his belly and lay down in the street to see if he could peer inside, as cars honked and changed lanes to avoid him. But the hole was too small for him to make out anything below the surface.

We found a matching manhole cover on the other side of the river, just north of Lake Street and again, just east of the median on LaSalle. We were foiled here, too, as this one was not just locked but cemented shut.

We had better luck finding tunnel remnants on Washington Street. On the west side of the river, Washington passes under the Ogilvie Transportation Center. There’s an eastbound lane of traffic, a westbound lane, and curiously, a center lane, too.

Jacob, who wrote the introduction to Greg Borzo’s book on the history of Chicago’s cable cars, pointed out a metal seam running through the street. Whereas the outside lanes of traffic were paved with asphalt, this center lane was covered in a concrete pad.

“This is definitely a remnant,” Jacob said. “I’m almost 100 percent sure this is the cable car tunnel under here. This is actually a concrete pad. This supposedly covers up the portal.”

Unfortunately, this pad-covered portal was not going to take us anywhere deeper than street level. There would be no tunnel access for us, at least not on this trip. But the Forgotten Chicago crew did help me catch sight of interesting, overlooked elements in the built environment I would have otherwise missed. In other words, they did what they do best.

If you want more historic cable car remnants still and can’t wait until next week, check out Greg Borzo describe what else is left of that old school transit system in the audio above.

Dynamic Range showcases hidden gems unearthed from Chicago Amplified’s vast archive of public events and appears on weekends. Greg Borzo spoke at an event presented by Chicago Public Library in January of 2013. Click here to hear the event in its entirety.

Robin Amer is a producer on WBEZ’s digital team. Follow her on Twitter @rsamer.