Songs about Chicago

By Tony Sarabia, Richard Steele

Songs about Chicago

By Tony Sarabia, Richard SteeleTony Sarabia: When thinking about my picks, I made a conscious effort to stay away from the more commonly known “Chicago” songs; you know the one I’m talking about.

My picks cover issues of poverty, architecture and weather. Let’s begin with poverty.

It’s too bad this song was released in 1969, because by then, the public’s enthusiasm for LBJ’s War on Poverty began to wane. Had Mac Davis’ muse clicked just four years prior, this socially conscious song could have been used by the Johnson Administration.

Nevertheless, “In The Ghetto” was and remains a powerful song, even if we don’t use the term “ghetto” these days. The original title of the song was “The Viscous Circle”. When I hear the song I envisioned an impoverished Chicago neighborhood back in the late 1960’s such as the west side, which was still smoldering from the post MLK assassination riots. Snow and cold paint an even starker picture of a baby born into a poor family only to grow up poor and resorting to crime only to meet a violent death.

The dead man’s own son is born shortly after and we are left wondering if he will meet the same fate. Mac Davis goes beyond pulling on the heart strings of listeners and implores us to do something about poverty.

Elvis Presley was in superb form during the recording session and not only did the session result in this song which peaked at #3 on the Billboard Charts, but also Suspicious Minds and Kentucky Rain. This was the first socially conscious song Presley recorded, and his first Top 10 hit in four years.

If Presley turned down the song, it was slated to be recorded by football player and minister: Rosie Grier. What remains a mystery is why Mac Davis chose Chicago as the setting for his story.

This is not a song about architecture per se but its roots are planted firmly in a particular space whose architecture significantly affected its residents and provided inspiration for this song. “Mecca Flat Blues” is a reference to the Mecca Flats; a massive apartment building in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood that was designed in 1891. Mecca Flats was Chicago’s largest 19th century apartment houses; a multi-unit building when none really existed. The building was innovative for its time: an exterior landscaped courtyard and two monumental interior atria. Outside courtyards dot Chicago today but there are no interior atria like what existed in Mecca Flats; a space that acted as an interior street for its residents.

By the 1920’s the building was populated by African Americans as a result of changing demographics and the continued migration from the south. Architecture Professor Daniel bluestone has written about Mecca Flats and says by the 1920’s Mecca Flats was the most visible massing of African Americans on the south side of Chicago

Even before that, in 1922, he recorded 300 piano rolls for Columbia Music Roll Company. I love this song because it really provides a glimpse into a long lost chapter of Chicago architectural and social history. Sadly, Mecca Flats was demolished in 1951; now that’s reason to sing the blues.

We don’t call Chicago the Windy City because of its wind but try telling that to outsiders. “Chicago Wind” is the title track from the Hag’s 2005 release and I appreciate Merle Haggard‘s disclaimer right at the top of the song: “I don’t know a lot about Chicago….” Assumptions about our wind aside, this is pure honky-tonk Haggard: a shuffle beat with some great guitar licks and Haggard’s laid back drawl.

We’re also talking to author Mike Czyzniejewski, who has been working on a novel about Wrigley Field for almost four years. Even longer, if you count the twenty two years he’s spent doing ‘research’ selling beer in the stands every summer. When his publisher got wind of his Chicago Stories, however, he told Czyzniejewski that the Wrigley project had to be put on hold.

Chicago Stories is basically series of what-ifs and mash-ups for Windy City junkies. What if Jane Byrne spent her nights in Cabrini Green chatting with her new neighbors about Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks. What if Jane Addams left Hull house for the burbs? What if Blago got a prison tattoo? What if Leopold and Loeb rode the Ferris Wheel?

The funny thing is, Czyzniejewski doesn’t live in Chicago. For 17 years, he’s taught creative writing at Bowling Green State University in Ohio, where his students don’t even recognize half the names and references in the book. Czyzniejewski will stop by Eight Forty-Eight on his way to a new professorship in Missouri to share some of his stories and sing along with our picks. His Chicago musical tastes were forged when he left the city seventeen years ago, so beware of grunge:

Richard Steele:

The famous Nat “King” Cole has deep Chicago ties. He grew up here and was among the most successful of those who attended DuSable High School and benefited from its famed music program. This composition, “Little Joe from Chicago,” was written by pianist/composer Mary Lou Williams. She spent some time in Chicago in the 1930s, but no one knows if that had anything to do with this song title. It did seem appropriate for Nat Cole when he recorded it in 1941, given his local roots. The song talks about a guy without much formal education, but a lot of street smarts. Nat does fun up-tempo vocals and some fine piano work.

They followed this up with a release from their second album. It was called “L.A. Goodbye” and stylistically, it was totally different from the hit record they had one year earlier. It was a great song, and even though it didn’t sell nearly as well, it was a certifiable hit in the Chicago music scene. The song had a poignant meaning for the band: The lyrics talked about memorable things in L.A., and having to leave them behind to come back to Berwyn after a long absence.

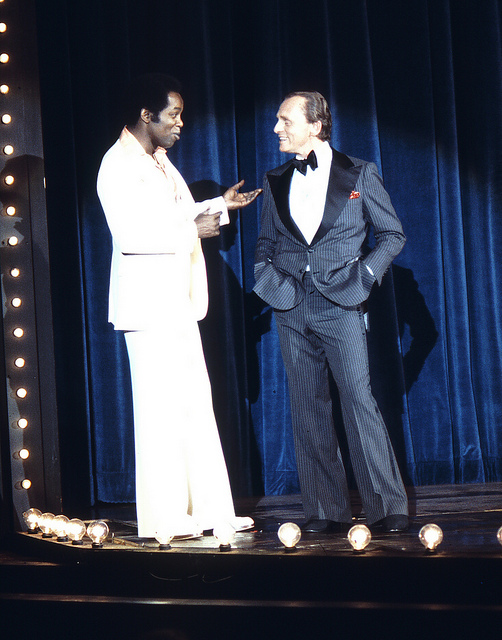

The late Lou Rawls was born and raised on Chicago’s South Side. He was a gospel singer, turned jazz singer, turned R&B and pop superstar. Rawls had a 40-year career in music, which included winning several Grammys. One of the things he’s most remembered for is his work on behalf of the United Negro College Fund. At one point, the yearly telethon was called The Lou Rawls Parade of Stars.

His 1967 recording of “Dead End Street” was a reflection of his life growing up in Chicago. The song’s famous monologue most certainly contributed to a Grammy win.