Paul Williams: The first rock critic, and one of the best

By Jim DeRogatis

Paul Williams: The first rock critic, and one of the best

By Jim DeRogatis

Most of the history books would have us believe that the business of writing about and critiquing rock ’n’ roll was invented and perfected by Rolling Stone magazine, launched by Jann Wenner in San Francisco in 1967. But as with so much about that fabled Summer of Love—or, indeed, about the thumbnail musical histories of any era—that version of the roots of rock criticism and journalism is complete and utter bull, and the real hero is ignored as we celebrate the myth.

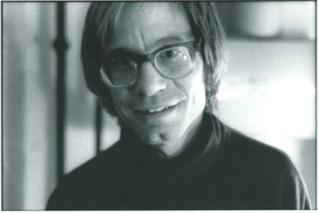

That hero, Paul S. Williams, died on March 27 after a long and difficult battle with dementia. He was 64.

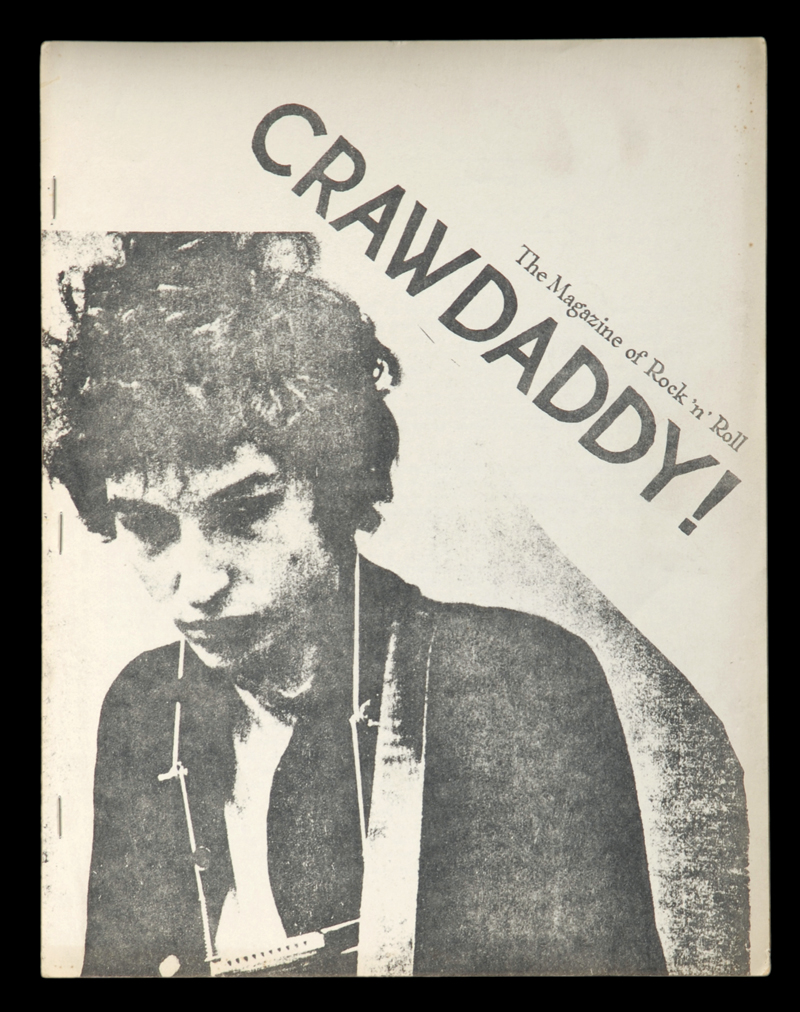

Taking his inspiration from the world of science-fiction fanzines, do-it-yourself magazines published out of sheer passion by fans who somehow commandeered time on a mimeograph machine, Paul Williams the music critic (not to be confused with Paul Williams the songwriter) was a precocious 17-year-old kid from Boston attending Swarthmore College in 1966 when he launched Crawdaddy!, the first American magazine devoted to serious coverage of rock ’n’ roll.

Such was the jump that Williams had on everyone else that Wenner came to him a year later when he started Rolling Stone to ask for some advice. Williams told the future publishing magnate that what readers wanted most was hard information about the musicians they loved. “I wasn’t interested in giving it to them,” Williams told me when I interviewed him in the late ’90s. “To me it was about what we could learn about each other through our responses to music. I recognized from the beginning that Jann would leave me in the dust, but that was fine. I didn’t even try to compete.”

Indeed, Williams left the magazine he founded in 1968—though by that time, under his editorship, Crawdaddy! had published many of the most important voices of early rock criticism, including Jon Landau (future manager of Bruce Springsteen), Sandy Pearlman (future manager of Blue Oyster Cult and producer of the Clash’s second album), and most importantly Richard Meltzer—the first true individualist in rock writing, predating and inspiring even the great Lester Bangs. Williams gave all of them the most valuable gift any editor can give a writer: the space and the freedom to make a mess on the page. But he never stopped writing himself.

Post-Crawdaddy! Williams was recognized as one of the world’s foremost authorities on Bob Dylan and Neil Young; he returned to the world of science fiction to become the literary executor of author Philip K. Dick, and he wrote more than two dozen books. My favorite was Rock and Roll: The 100 Best Singles (1993), which showcased his greatest trait as a writer: the ability to unleash a relentless, persistent, but always convincingly argued tidal wave of passion about the music he loved. His prose made resistance futile, dragging you along in its wake, and almost always for the better.

Williams had some extraordinary experiences as a music writer. He flew into Woodstock on a helicopter while sitting next to Jerry Garcia; he hung out at the recording sessions for Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys’ aborted Smile album; he clapped and chanted with the rest of their friends at John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s Montreal Bed-In and the recording of “Give Peace a Chance.” But he never bragged about any of those accomplishments—these stories were shared more with the usual rush of gleeful enthusiasm and boyish amazement—and he didn’t remain rooted in the past.

My second favorite Williams book is The Map or Rediscovering Rock and Roll (a journey) (1988), which chronicles how he fell in love with rock and rock writing anew in middle age, and how he intended to take pleasure from continually discovering new sounds through the rest of his life. In 1993, he resurrected Crawdaddy!, once again as a self-published fanzine largely written by himself, but eventually incorporating other promising voices of a new generation. And his writing about Kurt Cobain was as emotional and insightful as his writing about his earlier idols Dylan and Young.

Williams reveled in being an editor again, and for about a decade, he churned out the new version of his old magazine from the home near San Diego that he shared with his third wife, singer and songwriter Cindy Lee Berryhill, and their son Alexander, who was born in 2001. Berryhill blamed Williams’ early-onset dementia on a serious head injury that he suffered in a biking accident in the mid-’90s. Eventually, it became so bad that he was confined to hospice care, and last week, it claimed his life.

Among the tributes issued in the days after his death were several from musicians that Williams loved. Patti Smith guitarist Lenny Kaye, himself a pioneering rock writer, said, “Paul Williams was an insightful and heartful wordsmith who showed how to write about rock ’n’ roll in a way that illuminated the music as art. He set me on a path to understanding music’s potential as a vehicle for personal expression and transcendence. His intelligence and ever-curious and open mind allowed one to write about music as if it were music itself, a celebrant of the creative muse, and whenever I string words together or play a guitar solo, I think of him as my ideal listener.”

Added Brian Wilson: “Paul Williams was just a kid when he came to my house when I was making Smile. We talked a lot and I played him acetates of my new music. He really dug it and I’ll always remember that. He started Crawdaddy! and wrote a lot of great books. Paul died this week and I want to say I’m sorry to his family for their loss. Love and Mercy, Brian.”

A hippie to the core, though in the least obnoxious sense of that word, Williams had been satisfied with Crawdaddy! reaching 20,000 readers under his initial reign—a stark contrast to Wenner, who dreamed of world domination for Rolling Stone from the beginning. I probed that issue a little more when we talked about why he quit as editor and publisher in ’68. “By then, the New York Times was reviewing the new Beatles album when it came out, and there was no longer a need for the crusade which I had been on, to get people to try to take this stuff seriously,” he said. “I had a lot of fun with it, but by then it was obvious that people were taking this stuff far too seriously.”

Perhaps the best way to assess Williams’ legacy is to note that he took rock ’n’ roll as seriously as life itself, but never so seriously that he stopped having fun with it, or shut out its ability to help us better understand one another. He was a crusader, to be sure, but one of the very best sort.

Follow me on Twitter @JimDeRogatis or join me on Facebook.