Pro-Cop or Sympathetic to Laquan McDonald, One Thing is Certain: the Judge is Anti-Media

By Jim DeRogatis

Pro-Cop or Sympathetic to Laquan McDonald, One Thing is Certain: the Judge is Anti-Media

By Jim DeRogatis

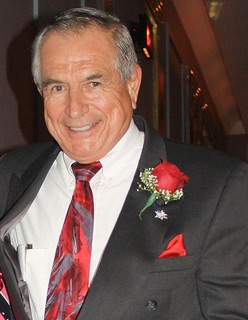

In a fascinating piece posted on The Chicago Reader’s Web site on Monday, reporter Steve Bogira dug deep into one of the most controversial judges on the bench in Cook County: Vincent Gaughan, who now is set to hear one of the most controversial cases in Chicago history, the trial of police officer Jason Van Dyke in the shooting death of Laquan McDonald.

Seventy-four and a 25-year veteran of the bench, Gaughan has a fascinating past, as Bogira revealed: In the middle of the night in April, 1970, as a 28-year-old DePaul University law student and “nervous” Vietnam veteran, the future public defender and eventual judge fired off several shots with an M1 rifle from his bedroom in his parents’ house in Lincoln Park, nearly hitting the neighbors next door and the police officers who responded.

The situation could have turned very ugly, as the one with McDonald did, Bogira writes. But it was defused when Gaughan asked to talk to a priest from DePaul and “an Irish sergeant” among the responding officers. In the end, he was calmly carted off to jail, a very different ending than the McDonald story, and one that Bogira theorizes could make Gaughan sympathetic to the victim—though the reporter also notes that the judge is an American Legion hardcore law-and-order type (and one who I would add is in the notorious, imperious, and gag-happy mold of Chicago Eight trial judge Julius Hoffman).

“I don’t know what happened to the criminal charges lodged against [Gaughan],” Bogira writes. “The Chicago Police Department said it had no records of the arrest, and that records of an incident that took place that long ago likely would have been purged.” A Freedom of Information Act request is pending. Meanwhile, Gaughan isn’t talking.

“I don’t do interviews or any of that,” the judge told the reporter. “God love you, take care.”

Gaughan may not do interviews, but he is intensely aware of his press coverage, even as his disdain for the press is obvious—or at least it was to me, during my role in the R. Kelly trial.

As The Chicago Tribune noted in a story on Dec. 29, in the months before the 2008 trial of R&B superstar R. Kelly on 14 counts of making child pornography, Gaughan traveled to California to examine how court officials there handled the intense public and media attention during the trial of Michael Jackson for molesting an underage boy. Many also thought he was emulating Judge Lance Ito, who had heard the O.J. Simpson case.

“He said repeatedly in the run-up to the R. Kelly trial that his primary concern was for a ‘fair trial’ and other concerns are ‘secondary,’” Trib reporter Steve Schmadeke wrote.

What Gaughan called fairness, however, many in the legal community called obfuscation, as well as a possible star-struck bias for Kelly and the defense, and a definite bias against the media.

As the press documented at the time, and this blog reminded readers in its Timeline of the Life and Career of R. Kelly in 2013, the case took more than five years to go to trial after Kelly’s indictment and arrest. Some delays were perhaps unavoidable: One was because Gaughan fell off a ladder in his home, and another came when one of the prosecutors had a baby. But most of that long wait remains unexplained: Every few weeks for five years, at a scheduled hearing, the defense and prosecution would gather in Gaughan’s courtroom, and he would almost always immediately convene with them to closed chambers, where records of the proceedings were sealed.

In April 2008, The Chicago Sun-Times, The Chicago Tribune, the Associated Press, and WBEZ/Chicago Public Media petitioned Gaughan to make all Kelly-related court records public, release transcripts of several secret hearings, and lift a gag order on the attorneys. A motion also was filed before the Illinois Supreme Court.

Both Gaughan and the higher court rejected these requests for what many experts say should have been public information, and to this day, the voluminous records of what happened for five years in the Kelly trial remain sealed and a mystery to anyone interested in the case.

When the trial finally started in May 2008, Kelly’s defense attorneys sought my testimony as the reporter (then at the Sun-Times) who anonymously received the videotape at the heart of the case. Sun-Times lawyers fought the subpoena, citing the reporter’s privilege, the special witness doctrine, the Illinois Constitution, and the First Amendment. Gaughan rejected all of those arguments, as did the Illinois Court of Appeals, and finally the Illinois Supreme Court.

Told by the paper’s brilliant First Amendment attorney Damon Dunn that to testify would set a damaging precedent for every reporter in Illinois, he advised me to decline to answer any question because of the Fifth Amendment: If I talked about touching much less watching a video tape that the newspaper and prosecutors said was child pornography, I would be incriminating myself in a felony. Then, too, I could not selectively answer some questions and refuse to answer others—such as any demanding the names of my sources.

In the end, like a mobster or a crooked politician, I had to “take the Fifth” 15 times in response to 15 questions while sitting on the witness stand next to Gaughan, though every time, I also mentioned the First Amendment, and I was ready to go to jail myself if the judge told me to shut up about that. Thankfully, he did not.

“Thanks; that’s exactly what we wanted you to do,” defense attorney Ed Genson told me as I finally left the courtroom. And I’ve never felt more sick to my stomach.

About a week later, Kelly was acquitted—and after years of vowing that he would not allow the trial to become “a media circus,” Gaughan, ever mindful of his own image in the eyes of the press, paid for and threw a party at a bar for all of the reporters who covered the story in his courtroom, as well as the attorneys for both sides.

“Dress is casual. Come and celebrate the trial’s conclusion and everyone’s hard work,” read the invitation that he he had his press rep send out.

“It was a hoot,” one reporter who went told me. “Everyone was loose and relaxed.”

I wasn’t invited and would not have gone if I was: The end of the trial of a man who, according to court documents that are public, had illegal sexual relationships with many underage women, ultimately causing quite a few of them considerable pain and trauma, would not have been something to celebrate, no matter what the verdict was.

I wonder if Judge Gaughan will throw another party after the trial of Van Dyke? Even more than the Kelly case, this is a situation where no one involved will have cause to celebrate, regardless of the outcome.

Follow me on Twitter @JimDeRogatis, join me on Facebook, and podcast or stream Sound Opinions.