Remembering Lou Reed, dead at 71

By Jim DeRogatis

Remembering Lou Reed, dead at 71

By Jim DeRogatis

Shortly after the news was broken by RollingStone.com, I learned about the death of Lou Reed via an email from the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, which was seeking help in putting the contributions of the 71-year-old musician in perspective. I quickly realized I never could do better than the two artists who, with Reed, did more than any others to shape my thoughts about rock ’n’ roll.

Brian Eno, that studio wizard and musical philosopher, often has been quoted as saying of the band Reed led through four brilliant studio albums that the Velvet Underground never sold a lot of records in their time, but everyone who bought one started a band. As it happens, Eno never actually said that—it’s one of those apocryphal sayings that never has been properly sourced—but he certainly agreed with the sentiment, because I asked him, and he echoed something that the third figure in my particular Holy Trinity, Lester Bangs, actually did write:

“Modern music starts with the Velvets, and the implications and influence of what they did seems to go on forever.”

Certainly this is to say that punk, glam, noise-rock, and its diametric opposite slo-core are unimaginable without what Reed and John Cale did in the Velvets and on subsequent solo albums. (Reed’s studio discography alone numbers 22 discs.) But beyond that, Bangs meant—and again, I know this because I asked him—that the Velvets more than any other band (yes, more even than the Beatles and the Stones) showed that rock ’n’ roll (always his preferred term) could and sometimes should be seriously accepted as capital-a “Art.”

Everything Reed ever recorded was based on the premise that this seemingly simple and crude sound—three chords and an attitude—was in fact without boundaries and of limitless potential to address the most complex themes and deepest emotions of the human experience, just like literature or poetry or classical music or any other higher pursuit we could name or aspire to. What’s more, we could grow with this music throughout our lives, because it is a life force itself, as he so wonderfully put it when writing about a young girl on Long Island (though in reality he was writing about himself and all of us) in the song he called “Rock and Roll”:

“Jenny said when she was just five years old/There was nothin’ happenin’ at all/Every time she puts on a radio/There was nothin’ goin’ down at all—no not at all/Then one fine mornin’ she puts on a New York station/You know, she don’t believe what she heard at all/She started shakin’ to that fine, fine music/You know her life was saved by rock ’n’ roll/Yeah, rock ’n’ roll”

What an idea: a life saved by rock ’n’ roll. Hyperbole? Not to me. That was certainly how me and my buddy A.J. DiMurro felt when we saw Reed perform The Blue Mask at the Bottom Line in New York after standing on line in the February frost for four hours. It was how me and my lifelong friend Jim Testa felt when we saw him play New York after an opening set by the Feelies (who had a side project Velvet Underground tribute band!) at the Beacon Theater, and it was how me and my buddy George Latanzio felt when we saw him reunite with Cale and play a work-in-progress called Songs for Drella at St. Ann’s Church in Brooklyn. It wasn’t necessarily how I felt when I saw him doing his tai chi moves in between songs onstage at Navy Pier during the last show I reviewed, but it’s how I still feel each and every time I play my Velvets and favorite solo albums.

What I’m saying is that in no small part, Lou Reed is why I’m here today, writing about music in this space, talking about it on Sound Opinions, teaching the art of criticism at Columbia College Chicago, and with a pile of books to my credit, some of them all or in part about the man who wrote those words.

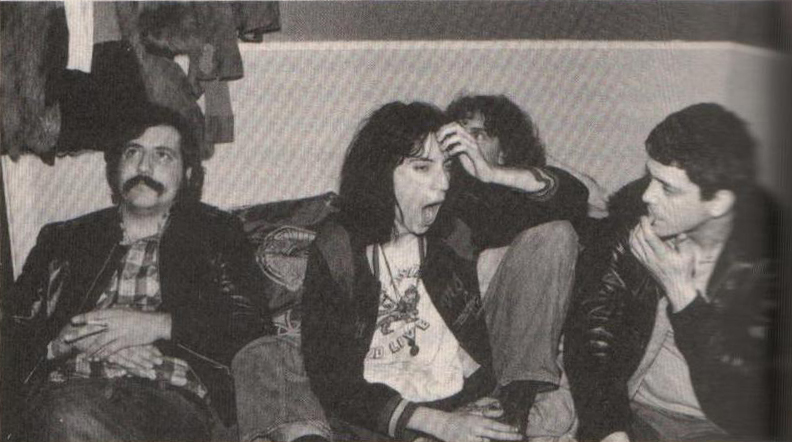

Now, hero or no, I interviewed Reed a half dozen times over the years, and it must be said that he was the nastiest, orneriest, most intimidating, and just plain meanest artist I’ve ever met. This was of course shtick—in part.

The template had been set by the infamous series of interviews/wrestling matches that Reed and Bangs did throughout the ’70s. The godfather of punk knew that’s what every other journalist would expect, and at least in part, he was temperamentally inclined to give it to them. He did not suffer fools lightly and had no hesitation to cut you down with, “That’s the stupidest question I’ve ever been asked; next!” while blowing the foul-smelling smoke from a Cuban cigar in your face.

On the other hand, the last time I interviewed Lou and he got all Lou-nasty on me, I told him I was just going to hang up if he didn’t want to talk. Whereupon he instantly apologized, and we proceeded to have one of the best chats we’d done, ending when he blew my mind by asking me to send him a signed copy of my Bangs biography Let It Blurt. (Still, even that didn’t tempt me to try to tussle with him again when I was writing the overview essay and connective tissue for my 2009 book, The Velvet Underground: An Illustrated History of a Walk on the Wild Side, the reason I got that call from Australia, as well others from France, Italy, and all over the U.S.)

In stark contrast, Chicago area home girl Laurie Anderson is one of the most pleasant artists I’ve ever interviewed. She survives Reed as his third and last wife, and it’s impossible to imagine her loving that man who was so unlovable in public if he acted the same in private. Was big, bad Lou really just a Teddy bear at heart, at least after he got clean and sober? Hard to say, but let us not forget the emotion he showed for others in his music, where it mattered most. As always, Bangs put it best, in a 1979 review of The Bells:

“Lou Reed is a prick and a jerkoff who frequently commits the ultimate sin of treating his audience with contempt. He’s also a person with deep compassion for a great many other people about whom almost nobody else gives a shit. I won’t say who they are, because I don’t want to get too schmaltzy, except to emphasize that there’s always been more to this than drugs and fashionable kicks, and to point out that suffering, loneliness and psychic/spiritual exile are great levelers.”

In the end, the answer to the question, “Who was the real Lou Reed?” doesn’t matter at all, because now he is gone, and as with any great talent, the art is what will live forever. To that end, I offer a baker’s dozen of his greatest songs, listed in chronological order, and keeping in mind that it easily could have been 100 tunes, if not more. And, because it seems especially appropriate, I’ll tack on the interview I did with Reed circa the release of Magic and Loss, his 1992 concept album about death and dying.

Farewell, Lou. We’ll miss you. Thank you for saving our lives.

1. “Run Run Run” from The Velvet Underground & Nico (1967)

2. “Sister Ray” from White Light/White Heat (1968)

3. “Candy Says” from The Velvet Underground (1969)

4. “Pale Blue Eyes” from The Velvet Underground (1969)

5. “Rock and Roll” from Loaded (1970; this version from 1969 Live)

6. “Satellite of Love” from Transformer (1972)

<

7. “How Do You Think It Feels” from Berlin (1973)

8. Metal Machine Music (1975)

9. “Kill Your Sons” from Coney Island Baby (1975)

10. “Waves of Fear” from The Blue Mask (1982, this version live at the Bottom Line—hey, A.J., remember that show? I know you do!)

11. “Underneath the Bottle” from The Blue Mask (1982)

12. “Small Town” from Songs for Drella (1990)

13. “Sword of Damocles” from Magic and Loss (1992)

Love & Death & Lou Reed

By Jim DeRogatis

Request magazine, February 1992

From his wild glam-rock days in the mid-’70s until he bottomed out in the early ’80s, Lou Reed defined the words “high risk.” He tied up with a microphone cord and shot speed on stage, had a torrid affair with a transsexual named Rachel, and sank deep into alcoholism and drug addiction. Not many rock ’n’ rollers could tackle a sixty-minute concept album about death without sounding hopelessly pretentious. Reed isn’t completely successful either, but Magic and Loss, his twenty-first solo album, carries the credibility of a survivor.

In one of the album’s most effective moments, Reed, standing at the deathbed of a friend, writes, “If I was in your shoes / So strange that I am not / I think that I would fold up in a minute.” “There’s an understatement,” he says, puffing on a foul-smelling Cuban cigar (he says he doesn’t inhale). “Put it this way: I think it’s possible that a listener might take my descriptions of things seriously because I have a track record to prove that I know what I’m talking about, and I have a background as an artist of being faithful to the listener and truthful. All great writers, at a certain point in life, have to deal with certain really basic, classic themes that go all the way back to the Greeks and Romans: Birth, life, and death—that’s it. I think at this point I’m mature enough to be able to write with some veracity about one of those subjects.”

Magic and Loss arrives at a point where Reed, fifty, is looking back at his long career, even though he claims to hate nostalgia. He recently compiled a three-CD box set for RCA that sums up his solo career before he moved to Warner Bros. for 1989’s New York, and Hyperion, Disney’s book division, published Between Thought and Expression, which collects lyrics from Reed’s solo career and his days as the lead singer and guitarist with the Velvet Underground. “It’s as close to autobiographical as you’ll get from me,” he says. According to his song, “Some Kinda Love,” “Between thought and expression / Lies a lifetime.” “Yeah, mine,” Reed says.

Reed is one of rock ’n’ roll’s greatest chameleons, second only to David Bowie, who stole the concept of periodically reinventing yourself from Reed in the first place. At various times in his solo career Reed has been a gender-bending glam star (Transformer), an art-rocker (Berlin), a metalhead (Rock ’n’ Roll Animal), and a punk (Street Hassle). After producing two brilliant albums about the tortures of kicking drugs and alcohol—1982’s The Blue Mask and 1983’s Legendary Hearts—he foundered for several years before finding his muse again on New York, an overweening album about the continuing decline of his beloved hometown, and 1990’s Songs for Drella, a touching tribute to the Velvets’ mentor, Andy Warhol, recorded with former bandmate John Cale.

The persona Reed has adopted these days is that of the Serious Writer; all that’s missing is the cardigan and pipe. He proudly notes that lyrics from New York have been printed on the op-ed page of The New York Times, and he talks at length about the joys of writing on a laptop computer. His recent efforts sound less like his best rock songs—“Sweet Jane,” “Rock ’n’ Roll,” or even “Walk on the Wild Side”—than long-winded prose poems set to music. In his book, Reed cites “The Bells” as his favorite lyric because it came all at once as he stood at the microphone, but there seems to be little of the spontaneous, improvisational spirit of the Velvets or his best solo efforts on his recent albums.

“Don’t be too sure,” Reed replies in his familiar nasal monotone. “When I’m writing, I try to leave a lot of room for certain things to happen. I saw Garrison Keillor on TV, and Larry King asked him this question about writing. He said something really interesting, I thought, because it applies to me. He was lucky, he said, because God made him an insomniac, so he’s up at odd hours and he sits down and he writes. There’s no one else around, it’s totally quiet, and at that hour of the morning you can figure out things that a really smart guy wouldn’t be able to figure out a couple of hours later. And that’s how I feel. You really have direct access to things. Almost everything on Magic and Loss was written at like five in the morning on a computer.

“Writing is hard. Any kind of writing is hard. On the other hand, it’s also really great, great fun. And it can also be excruciating.”

“Excruciating” is a word Reed uses a lot when talking about Magic and Loss. The album was inspired by two close friends who succumbed to cancer last year, a woman known as Rotten Rita back in the days of Warhol’s Factory and legendary songwriter Doc Pomus. But considering the number of gay friends Reed has lost and the chill that’s fallen over the New York art and music scenes, the specter of AIDS looms large over the album.

“I think if s unfair to categorize the album as being about death. I think of it as being a celebration about friendship and love and dealing with the loss of that,” Reed says. “I think it’s a very positive album, especially these days with AIDS, where younger people are being faced with loss way earlier than people would normally be facing it. Everybody is losing relatives and friends left and right, this is just a fact, and there’s no cure for it. You’re talking about something that’s fatal. You see these people doing ads on TV, HIV-positive, they look OK, but the rest of the story is that they will eventually die. There is no cure for this thing. HIV-positive means ‘leading into.’ What will Magic Johnson look like in a year? Will everybody applaud him when he comes out then?

“It’s a terrible situation. How do you deal with loss? We’re not trained to deal with loss. Our media keeps it away from us. People don’t want to hear about it. And yet it can be a very, very positive and inspiring experience in real life if you happen to be in the situation I was, watching people who were absolute giants. The guy on the record says, ‘Not a day goes by that I don’t try to be like you.’ And I’m trying to give that to the listener, that experience, because getting that from these people, then the loss is transformed. It’s not just loss, these people live on. And I try to demonstrate it to you rather than just tell you about it. The demonstration of it is the magic.”

Although he’s often accused of being a cynic Reed has always believed in the redemptive power of music. With the Velvet Underground he wrote of a girl whose “life was saved by rock ’n’ roll.” Between Thought and Expression includes a 1990 interview with Czech president Vaclav Havel, who talks of drawing strength and inspiration to fight the Communist regime from Reed’s lyrics. And Reed seems genuine when he says he hopes Magic and Loss will help some of his fans come to terms with losing a loved one.

“I am, in fact, already hearing that from journalists, of all people,” he says. “It’s something they don’t normally talk about, because who would you talk about that with? It would have to be someone very, very close to you. And yet I’m talking to people who will suddenly say, ‘My brother …,’ or ‘Six years ago, I had to go in,’ or ‘Both my parents died.’ It’s around a lot more than we know or speak about, and I don’t think that’s such a great thing. Talking is one of the cures. The thing that works for alcoholics and drug addicts is sharing, sharing of experiences. ‘Now listen to this one. They become funny. You can tell the most horrifying experiences, and it’s actually funny. When that happens, you’re on the way.”

The idea of devoting an album to one concept certainly isn’t new, though the form is usually associated with such overblown and mock-operatic works as Tommy and The Wall. Reed believes he’s breathing new life into the genre, although he’d never link his recent efforts with the Who or Pink Floyd, or even his own overblown but sporadically brilliant concept album, 1973’s Berlin. “I don’t think there’s ever been a really great album about just one subject at all ever, not that I can think of,” he says. “I think that I’ve assiduously discovered what I would call a brand new art form, which is a CD with fourteen or fifteen songs connected by a theme with a beginning, a middle, and an end and lyrics that can stand on their own as poetry.

“With the Warhol thing, Songs for Drella, I thought, ‘Jesus Christ, we could call this a new category, bio-rock.’ And here’s a chance for black rappers to do their constituents a great service. Just like I tried to introduce you to Warhol, the rappers could introduce you to Malcolm X or Langston Hughes or James Baldwin. I think Hammer should think about it. Michael Jackson should think about it. All they have to do is look at Songs for Drella, my Warhol album, this is how it’s done. It’s easy. It’s the writing that’s hard. You’re talking about sustained thought, which in America right now is not easy. It’s all quick editing.”

Some critics have pointed to Reed’s chronicling of the seamy underside of New York City as a prelude to the gratuitous sex and violence that gangsta rappers pass off as “urban realism.” On 1986’s Mistrial, Reed himself claimed to be the original rapper. But the first rapper to score a hit from one of Reed’s tunes is Marky Mark, New Kid Donnie Wahlberg’s pumped-up younger brother, who updated “Walk on the Wild Side.” “For what Marky Mark was trying to do, I thought it was an honest attempt at it, and on that basis I thought it was really OK, and so I approved that one. Now it’s a big hit, so that’s kind of nice,” Reed says, missing the irony of a lightweight popster crooning about the wild side. Then again, Reed didn’t think it was ironic when he sold “Walk on the Wild Side” to Honda for a scooter commercial, either.

Reed dismisses most of the rappers who approach him to sample his work as “terrible, simply awful.” Despite his long-standing love of new technology—he’s always experimenting with new recording techniques, and before this interview, he fiddled curiously with his publicist’s new computer Rolodex—Reed isn’t interested in sequencers or samplers. He’s a conservative when it comes to sticking with the two guitars, bass, and drums format. “There’s all kinds of ways to expand the format through the tone, choice of notes, taking those progressions and turning them inside out a little bit, mixing progressions or two styles that you normally wouldn’t think of, using space as a note. It doesn’t have to be the same old thing over and over. Plus, from a sound point of view, it’s astonishing the things you can do with guitars now.

“I finally have the technology working for me instead of against me,” Reed says. “I was generally losing to it. I put out a lot of records that are like demos, just completely dry, because I couldn’t stand the engineers and I couldn’t get what I wanted, so rather than them make it even worse, I just put it out dry. It’s been very, very difficult. I had to really immerse myself in the technical end of things by seeking out people who are much better than I am and asking them lots of questions. That’s kind of one of my techniques. I’m always looking to be around people who are way more advanced than I could ever hope to be. ‘Oh, how did you do that? Do that again. Show me how you did that’”

The urge to pick the brains of the people who are working for him may be the reason Reed hasn’t kept a band together for more than a few albums. He claims he has no interest in reuniting with any of his old bands, whether it’s the powerful Robert Quine-Fernando Saunders-Fred Maher group of The Blue Mask and Legendary Hearts era or the Velvet Underground. But Reed is nothing if not inconsistent, and the Velvets did in fact come together for one song in the fall of 1990 at a Warhol tribute in Paris. “It will never happen again. It was purely a moment in time,” he says now. “You must remember, I wrote, what, ninety-seven percent of the material for the Velvet Underground. These are things I’ve gone through on my way to making Magic and Loss. So I don’t want to—and I don’t, not in real life—look back. There’s nothing to be gained from it. You’re trying to grow and go forward, and the people you were with then are not where you are now. So it’s not a fair match up.”

Reed’s most memorable sparring matches over the years have been with members of the music press, with whom he’s had a love-hate relationship. He needs journalists’ accolades to feed his sizable ego, but he dismisses their criticism as unknowledgeable. (Before our interview, he was griping to his publicist about something Jon Pareles had written in The New York Times.) No critic has had as intense a relationship with Reed as Lester Bangs, however. Reed has outlived his old nemesis (Bangs died in 1982 after overdosing on Darvon, a muscle relaxant), but Bangs seemed to predict Reed’s future in a 1975 article entitled “Let Us Now Praise Famous Death Dwarves.”

“Lou Reed’s enjoyed a solo career renaissance primarily by passing himself off as the most burnt-out reprobate around, and it wasn’t all show by a long shot,” Bangs wrote. “People kept expecting him to die, so perversely he came back not to haunt them, but to clean up.”

“I think sometimes when people get obsessed with your work, it’s really dangerous for both of you,” Reed says of Bangs and, by extension, any fan who draws too close. “You can disappoint someone like that so easily when they find out just how human you are. They’d rather have this illusion of this, that, or the other thing. I’m not dealing on that level of illusion. That’s not the kind of magic I’m dealing in. What I’m dealing in is what’s on the record. That’s me at my best, when I have time and the ability for sustained thought to make it as good as I possibly can. Me in person can’t possibly be as good as that.”

Follow me on Twitter @JimDeRogatis or join me on Facebook.