Working with Lou, Part 3: The Velvets legend and the late Robert Quine

By Jim DeRogatis

Working with Lou, Part 3: The Velvets legend and the late Robert Quine

By Jim DeRogatis

This weekend, Sound Opinions will air its show-length tribute to the artist that Greg Kot and I consider one of the most important in rock history, and whose music arguably has meant more to us than any other: Lou Reed, who died on Oct. 27 at the age of 71.

Even for those of us who were lucky enough to meet and interview Reed several times, many questions linger about what the man was really like. For some insights into the artist in the days following his death, I turned to several musicians who were privileged to work on some of Reed’s best solo albums.

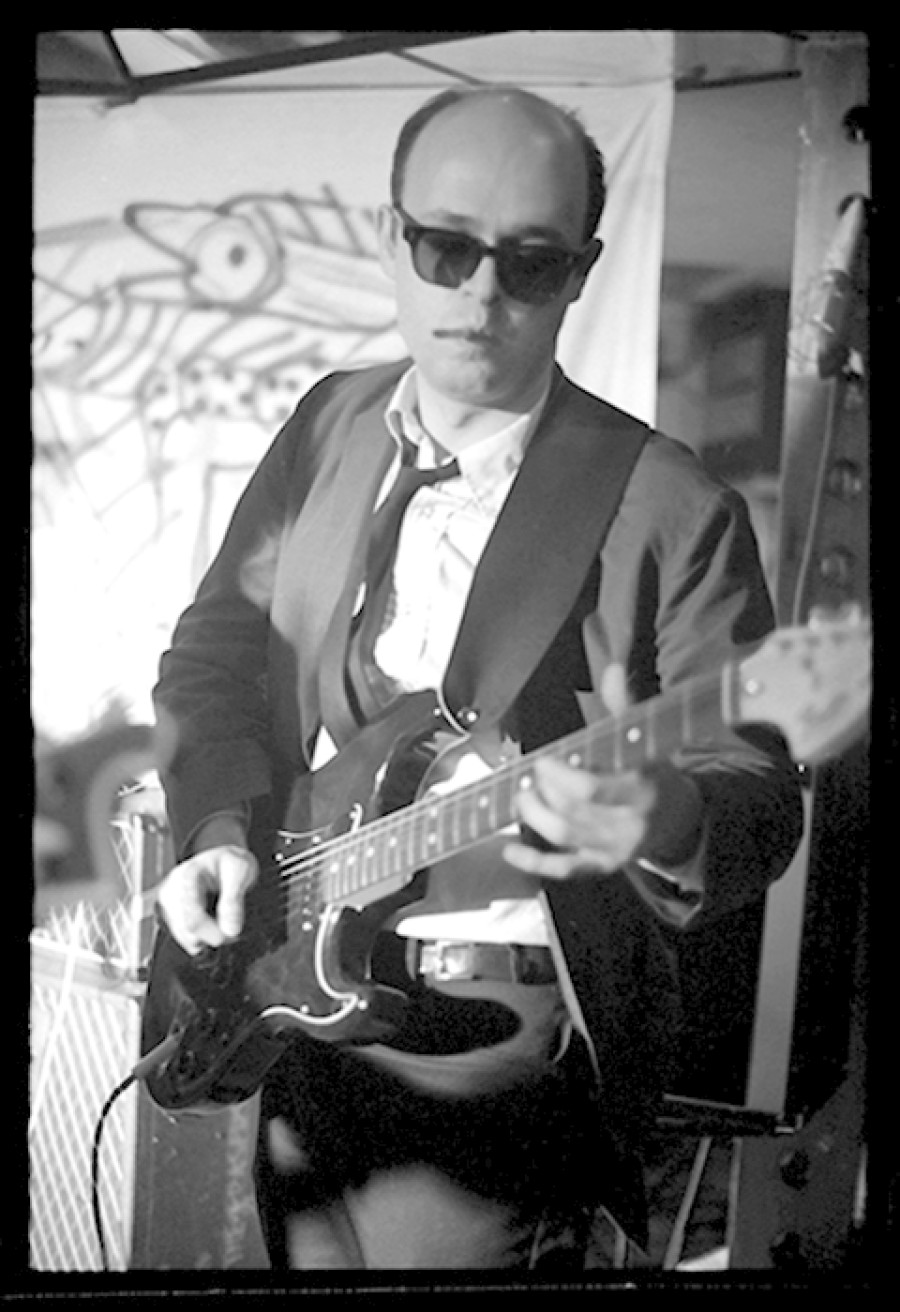

An incredible post-punk guitarist whose work elevated albums by Richard Hell and the Voidoids, Matthew Sweet (Girlfriend), Tom Waits, Brian Eno, and others, Robert Quine grew up in Ohio as a devoted fan of the Velvet Underground, following that group around the country with a reel-to-reel tape recorder. (His concert recordings eventually would be compiled and released as Velvet Underground: Bootleg Series, Vol. 1: The Quine Tapes.) In the early ’80s, Quine played with Reed on The Blue Mask, Legendary Hearts, and Live in Italy, but then the two had a bitter split.

I could no longer call Quine to ask about his thoughts on Reed the way I called Fred Maher and Jane Scarpantoni: Despondent after the death of his beloved wife Alice, Quine took his own life with an intentional overdose of heroin in 2004. But we spoke at length many times in the late ’90s when I was researching my biography of rock critic, Velvets champion, and Quine pal Lester Bangs. One of those interviews is posted in its entirety on the Webzine Perfect Sound Forever, but below are the portions of that talk that focus on his complicated relationship with Reed, as well as on Reed’s complicated relationship with Bangs, to whom the artist meant more than any other.

These comments are nowhere near as positive as those from Fred Maher and Jane Scarpantoni in the interviews I posted earlier this week, and I thought long and hard about including them here. But the creative friction he experienced with some of his collaborators is as big a part of Reed’s legacy as the mutual respect he evidenced for others. Witness his partnership with John Cale. And after Cale, Sterling Morrison, and Maureen Tucker of the Velvet Underground, I believe that Reed’s collaboration with Quine stands as the most fruitful of his career.

Q. How did you relate to Lester’s writing in Creem—what did you like about that?

A. Just the fact that he liked the Velvet Underground. The Velvet Underground had five or six fans in 1969, no matter what anyone says. I learned the hard way. I would try to join bands and they would say, “Who do you like?” And I would say, “The Velvet Underground.” Even in New York, that got you nowhere. But I heard Lester moved to New York, and I was in C.B.G.B.—this was shortly after I joined Richard Hell—and we hadn’t played live yet, I don’t think. I was working with Richard Hell, and somebody pointed out, “That’s Lester Bangs.” So I went up, and he was one of my heroes. He sort of had this look of blasé boredom, like he had heard it all before: “I’m a really big Velvet Underground fan, blah, blah, blah.” Nothing could get his interest up. I had thirty-five hours of unreleased Velvet Underground tapes that I had made myself in 1969—[but] he had been subjected to that. [He didn’t care.]

Q. The Blue Mask had just come out when I interviewed Lester in 1982, and I asked him about it. He thought it was wonderful.

A. I was still friends with Lou Reed [at] this point—I had done The Blue Mask and I was actually friends with him for a while, which was a very bad mistake.

Q. That’s fairly rare; I don’t think I’ve heard that sentence before: “I was friends with Lou Reed.”

A. Lou Reed was one of [Lester’s] heroes. Certainly he liked a lot more Lou Reed records than I did. It’s like Take No Prisoners—that sounds like really bad Jerry Lewis to me. The only Lou record he didn’t have anything good to say about was Growing Up in Public. So I was friends with Lou Reed about six months before Lester died [on April 30, 1982] and I was trying to somehow get them together. Lester was slightly envious that all of a sudden I was going out and seeing movies and going out to eat with [Lou]. I was really stupid, though; the first version of The Blue Mask which you never heard was much better. It’s the same record but he’s doing live vocals and he’s not trying to croon and he’s using some really heavy-duty obscenity—like the rape thing and “The Gun” is powerful. He cleaned up a lot of it. Because of my loyalty to my alleged friend at the time, I didn’t play Lester that stuff because he—Lou—wouldn’t have wanted me to. Finally at Thanksgiving, I got the permission to play Lester the mix—he sat there with headphones and he liked it; he said it was good but the lyrics were weak. Lou Reed asked me what he thought of it and I said, “He really liked it but he thought some of the lyrics were weak.” It was probably the worst thing I could have done. I was just so infatuated with being able to hang around with this guy, my hero. And I made a good record with him.

Q. After all this time, Reed still couldn’t take Lester’s criticism?

A. Coincidentally, my friendship with Lou Reed ended with Lester’s death. I’m going to skip ahead. When Lester died, I got the news Friday night. The next day I was sort of stumbling around in a state of shock. It was a sunny day; it was Saturday. I went up by his house and the window was open. I thought, “I could go up there and bellow his name, but I don’t think he’s coming out.” I was in a state of shock, ’cause I never had a friend die before, and I was just sort of a walking target. I was walking by Gramercy Park, and this very evil-looking black guy, like an old gangster from the ’40s, he had the phone cradled in his arm and I was walking by and he had a cigarette in his mouth and he grabbed my collar with one hand and points to the cigarette like he wanted it lit. I was too numb; I did it. If someone would have done that to me on a normal day they would have gotten hurt. Then I went over to Lou Reed’s house. When I told him that Lester died, he didn’t believe me. That marked the end of my friendship with Lou Reed, because he said, “That’s too bad about your friend.” But then he launches into a forty-five minute attack on Lester. He’s an egomaniac and that’s the way he is and that’s why he has no friends. If you’re not a yes man, you’re not his friend. He respected the fact that I wasn’t a yes man, but ultimately I had to go.

He mentioned the article in Creem when Lester describes Rachel [Reed’s transsexual lover in the ’70s]. He says, “Do you understand, Quine—this is a person I was close to. And he is calling her a creature and ‘thing.’”

For a while, when I was really like, “Lou Reed’ s my pal”—I was over at Lester’s house and I said, “He’s just a normal guy.” Lester said, “Bob, Lou Reed is not normal.” He pulled out the record of Walk on the Wild Side—with the pictures [of people in drag]—and he goes, “See this? This is a guy, Bob.” It put things a little in perspective for me.

Q. I learned about the Velvet Underground because of Lester’s writing. It made me fall in love with that music. Cale told me, “Lester kept Lou Reed afloat for ten years.”

A. It is my humble opinion that Lou Reed is an asshole. You can give this reason or that reason why he acted the way he did—he just kept going on and on about Lester. Lester had written this wonderful heartfelt obituary of Peter Laughner, where he ended it saying, “I wouldn’t walk across the street to spit on Lou Reed.” Lou had gotten a copy of that and he was reading this to me like he was looking in a mirror—that was the end of the conversation. When I left there, I said, “You know, I don’t think I can be friends with this guy.” I tried to back away from the friendship, which is something you can’t do with somebody that paranoid. I tried to do it over a six-month period, but I had to pay.

Q: But you did two other albums with Lou Reed, right?

A. He mixed me off Legendary Hearts; I’m barely audible on it. He did the Live in Italy record, which is not very good. If you read interviews with him, he’s like, “I know I am very good; quote me.” You know the song on Legendary Hearts called “Home of the Brave”? It’s about people that are gone, people that are dead. There aren’t many places for solos in that record, and I said, “I want to take a solo in this one.” And that sums up my feelings about Lester. That’s pompous of me, but…. What I did was I went direct through the board and it came out totally naked and brutal and what he did, he added a bunch of fucking slap-back echo to it. But that was my expression of my sense of loss. I sound like a pompous asshole.

Q. Reed was jealous of your guitar playing?

A. It is as simple as that. The reason I felt betrayed was I bullied him into playing guitar. I told him straight up if he doesn’t play guitar, I’m not working with him, so he played guitar again for the first time in a long time. I would force him to take solos. Then he got his confidence and he turned it into a competitive thing. If there is a competitive thing, there is no way I am going to win. Not when he is telling the guitar guy to mix me out, when people can’t hear me taking guitar solos. When he keeps me out of a mix to make sure I’m not being heard, he’s an asshole. I finally ran into him a couple weeks ago at a guitar store, and I just kind of walked by him. I wouldn’t say anything and walked out and he turns to the sales guy and says, “There goes one miserable motherfucker.” He tried to get me to come back and play with him for two and a half years, but I couldn’t take it anymore. He had a mutual friend ask if I would ever play with him and I said, “No, I’ll never play with him ever again.” That’s when he would start saying nasty things about me. Basically his stock answer would be, “Quine is a very very, very, very sick individual,” and that would be the end of it.

It’s an important story about Lester. You know, Lester, he would hold people up. Lester was sort of like me: He saw things in terms of good and evil. If somebody didn’t live up to expectations, then they had betrayed the gift.

Q. I’m not sure I understand the Lou Reed obsession. Why was Lester so fascinated with Lou?

A. Well, it’s the same for me. It’s like Little Richard—I’ve never met Little Richard, and I never bothered to see him, and he hasn’t done anything good in forty years. But if he walked in here, I would go fucking stone cold. I don’t give a shit about poetry or anybody’s lyrics—if I don’t like the music I’m not gonna bother, like the social issues the Clash are singing about.

Lou was, and still is—when you draw the line on his good stuff—he changed my life completely. Long before the Jefferson Airplane were talking about pot, he had a song called “Heroin.” This guy did not mess around. And that’s the reason. And once in awhile—he was not the same person I knew in 1969, but you saw sparks, and when you saw them, you knew. Lester never gave up on Lou Reed. Iggy Pop approached me once or twice about playing with him, but Iggy he had totally written off. He said that this guy was a moron and he would never make another good record. I would argue with him; I would say, “Listen, he has another record or two in him.” He would say, “No way.” Today, interesting enough, Raw Power is being reissued in a new Henry Rollins remix. I have a feeling it’s inferior. But I’ll have to buy it. Lester said to me once, “You know what I do when I go over to people’s houses? I look and I check their copies of White Light/ White Heat, and a lot of times they haven’t been played.” He did it to me. He said, “Bob, this is mint!” I said, “Lester, how many copies do you think I’ve worn out, you moron?” I literally had worn out seven or eight copies. I paid for it. It’s hard to imagine how completely unappreciated they were. That was the link that connected me to him—the fact that he gave this record a decent review—whereas [Rolling Stone’s] Ralph J. Gleason would be singing the praises of the Jefferson Airplane.

Q. You know the song “Rock and Roll”—Jenny’s life was saved by rock and roll—who believed it more, Lester or Lou?

A. I think in Lester’s state of mind, near the end, that Village Voice Pazz and Jop Poll, he was like, “Maybe something better will come around,” but I don’t have him around to tell me anymore. I think at this point things are better in that instead of people just paying lip service to the Velvet Underground or doing cop-outs like the wretched Cowboy Junkies or something—it’s been enough time now that another generation has sort of absorbed it. I got so immersed in it that I absorbed it. Sometimes when you hear a song by somebody like Yo La Tengo or Stereolab, they understand that thing.

A video clip of Quine performing “Rock and Roll” with Reed, Fernando Saunders, and Fred Maher at New York’s Bottom Line in 1983 follows, along with the song “Home of the Brave,” featuring Quine’s guitar-solo tribute to Lester Bangs. Also visit soundopinions.org to read my long historical essay and critical overview of Reed’s greatest band, which I wrote for the 2009 book I edited for Voyageur Press, The Velvet Underground: An Illustrated History of a Walk on the Wild Side. And follow me on Twitter @JimDeRogatis or join me on Facebook.