Refugees Resettled In Chicago Help Make Its Most Famous Cheesecake

By Deb Amos

Refugees Resettled In Chicago Help Make Its Most Famous Cheesecake

By Deb AmosDeb Amos/NPR

In Chicago, war refugees have a hand in the city’s most famous handmade cheesecake.

“People who come as refugees have great skills,” says Marc Schulman, the president of Eli’s Cheesecake, which has sold cheesecakes and other baked desserts since 1980. One-third of adult refugees arriving in the U.S. have college degrees, according to the Migration Policy Institute in Washington, a think tank that tracks the movement of people worldwide. And refugee employment is a successful model for finding skilled workers for a food business that has become high tech, says Schulman.

A cheesecake at Eli’s is still based on the simple recipe of the founder, the late Eli Schulman, Schulman’s father, who served his famous confections to political leaders and Hollywood stars. Marc Schulman wears the Cartier watch that Frank Sinatra — a regular customer — sent his father in 1987. This Chicago food factory now produces 300,000 portions of cheesecake a day, in addition to tarts and cookies for restaurants, airlines and grocery freezers. “The line has certainly evolved over time,” says Schulman.

The mixing and baking are computerized, so the 220 employees have to be highly skilled. Schulman recruits about 15 percent of the workforce from refugees resettled in Chicago. The employee list reflects the waves of flight from war-torn countries — Iraq, Bhutan, Kosovo, Congo, Myanmar.

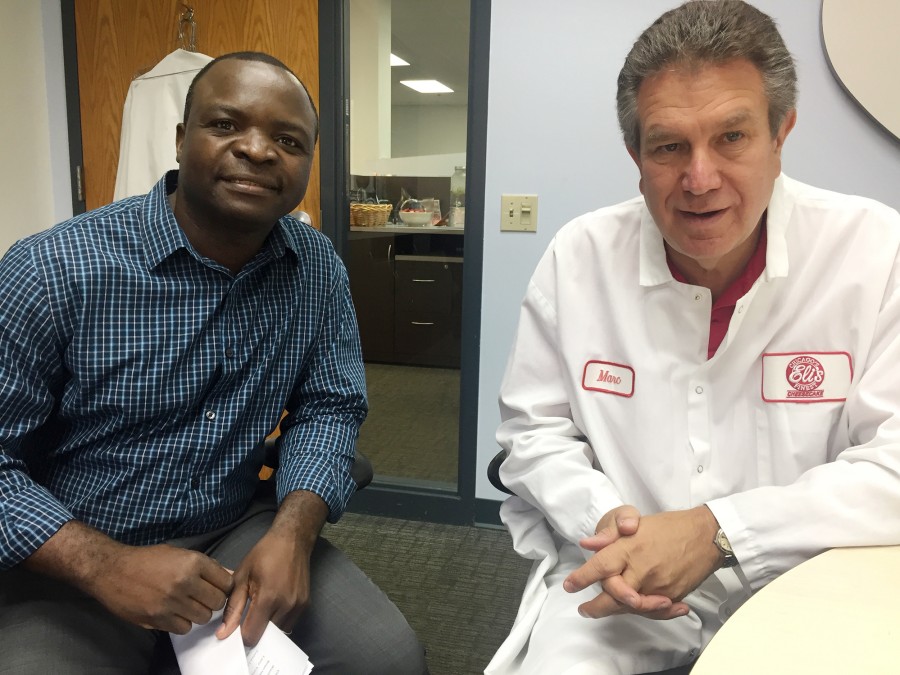

Elias Kasongo began working at the bakery in 1994 after fleeing unrest in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Having completed a year of college before fleeing his country, he found a job in the dish room at Eli’s. He was eventually promoted to the executive suite, getting a business degree at Northeastern Illinois University in Chicago along the way. Today, he is the purchasing manager, pricing Madagascar vanilla and organic cream cheese. He also serves on the board of RefugeeOne, a Chicago nonprofit that helps refugees start new lives.

“I’ve been here at Eli’s for the past 22 years. It’s my home; it’s a beautiful thing,” says Kasongo, who is now a U.S. citizen. The job was all he had when he was starting his new life in America. Today, he’s a homeowner.

“These are great performers, great people,” says Schulman, and he is ready to hire from the latest wave of Syrians, the most recent arrivals in Chicago.

To see how Eli’s Cheesecake is made you have to dress up like a scientist — white coat, covered shoes and hair, a mandatory hand wash before entering the factory floor. Inside, the mixing bowls are as big as bathtubs. The computerized production line is a complex alliance between workers and machines that pump out 6,000 pounds of batter a day. A two-story conveyor belt delivers the cooled cakes, 57 varieties, for hand-finishing and boxing.

The production leader is 46-year-old Zamira Bejrektarevic. She was a refugee from Bosnia, settled in Chicago in 1999. When she arrived she didn’t speak much English, but she had a decade of factory work experience in Bosnia.

“When I first came, I [worked] in cleaning, in the office,” she says. As her language improved, she was promoted to the manager position.

It’s a common story, says Schulman. Refugees tend to make long-term commitments to work, he says, at a time when there is a talent shortage for highly skilled jobs. They are highly motivated, he says. They have to be motivated just to get to the U.S. It can take years of interviews and security screenings. Then there are the hurdles of a new country, a new language and culture.

It is hard work, but it paid off for Ray Hermez, who works on the production line boxing finished cakes. He was a car mechanic in Iraq and was resettled in Chicago five years ago.

“I came as a refugee, but now, I’m a citizen,” he says. He got his citizenship this past January.

“We have many success stories,” says Schulman about his hiring strategy, which he insists is not charity. It’s good business, he says. “We have celebrated citizenship ceremonies with a number of our associates; we’ve seen individuals have children and buy homes.”

Schulman’s hiring strategy is used at other well-known companies in Chicago, including Tyson Foods and Trump International Hotel & Tower.

“Every major hotel works with a refugee agency,” says Sean Heraty, manager of workforce development at RefugeeOne. “Job retention is through the roof.”

Employers have “awakened to the potential of refugees,” says Kathleen Newland, at the Migration Policy Institute. That’s because they are hardworking and loyal and tend to stay on the job longer than American-born workers, she says.

“It takes someone to take a chance on you and say, ‘Hey, let’s see if he has the talent,’ ” says Kasongo, who turned his chance into a career. “It takes the talent.”

Copyright 2017 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.

9(MDI4ODU1ODA1MDE0ODA3MTMyMDY2MTJiNQ000))