Chicago’s first Mother’s Day

By John R. Schmidt

Chicago’s first Mother’s Day

By John R. SchmidtThis Sunday is Mother’s Day. Chicago first celebrated the holiday 103 years ago Wednesday–May 9, 1909.

The American version of Mother’s Day was started by Anna Marie Jarvis, after the death of her own mother in 1905. To honor all mothers, Jarvis asked people to wear white carnations on the second Sunday in May. The first observances were held in Grafton, West Virginia, where her late mother had lived.

By 1908 Mother’s Day was being celebrated in Philadelphia, San Francisco and a few other places. Meanwhile, Jarvis worked to spread the holiday. She sent pamphlets to women’s clubs in various cities, asking for help.

In Chicago, the Mother’s Day cause was taken up by Sarah Warrell. On May 4, 1909, the Tribune ran a short interview in which she described the holiday.

Warrell called on ministers, teachers, and charitable institutions to get out the word. Wearing the white carnation was the first step. Then people should use the holiday for positive action, to help the aged, the sick, and the needy. “If everyone in the city would volunteer to do what he could to observe the spirit of Mother’s Day, much happiness would result,” Warrell said.

May 9th came. Men, women and children were seen sporting the white carnation. Some groups, like the YMCA and the Grand Army of the Republic, had enlisted their entire membership. Pastors mentioned Mother’s Day in sermons, and in Oak Park, the First Presbyterian Church was filled with the symbolic flower. Carnations were also distributed at various hospitals and orphanages.

With less than a week’s publicity, the first Chicago Mother’s Day was a great success. During the next few years, the local movement grew. In 1910 Governor Deneen declared Mother’s Day a state holiday. Not to be outdone by a Republican, Chicago’s Mayor Harrison issued his own proclamation in 1911.

The holiday was a likely time to remind Chicagoans of the problems faced by unmarried mothers–”illegal mothers,” as they were then called. On Mother’s Day 1911, the St. Margaret Relief Society held a special meeting at the La Salle Hotel. Single moms told their stories to an audience of 200 local club women, asking for help to maintain the “maternity home for dependent women.”

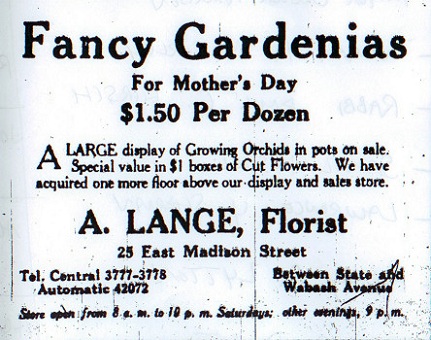

Chicago’s 1912 Mother’s Day was the biggest one yet. The holiday had become so popular that local florists ran out of carnations. The Tribune published a special section in which prominent Chicagoans wrote about their mothers. There was some talk about changing this first Sunday in May to a Parents’ Day–or maybe even having a separate Father’s Day.

Finally, in 1914, President Woodrow Wilson signed a proclamation designating Mother’s Day a national holiday. We’ve been celebrating it ever since.