Den Theatre’s Faith Healer: Short of Miraculous

By Kelly Kleiman

Den Theatre’s Faith Healer: Short of Miraculous

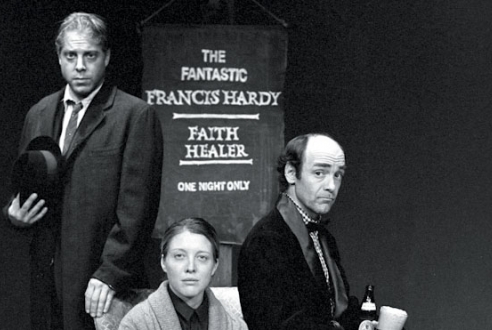

By Kelly KleimanPlaywright Brian Friel (“Dancing at Lughnasa”) is the bard of waning traditional Ireland, recounting the sad stories behind the jocund facade. In “Faith Healer”, he leaves Ireland without actually leaving it, addressing the quintessentially Irish question of how to reconcile faith with reality.

The names are significant: Frank refuses to delude himself or the others about the nature of his “gift,” if there is one; Grace clings to her belief that her husband is a blessing; and Teddy (Theodore, or “God’s gift”) turns out to be the only thing holding them together.

And their collective reflection on themselves and one another gains resonance from the three actors’ having played the roles under the same director (J.R.Sullivan) nearly 20 years ago, and from Osborne and Mortensen’s now-dissolved marriage. Yet with all these elements going for the production, it doesn’t quite make it.

Friel’s play is a bit long-winded, as though the playwright were simply intoxicated by the sound of his characters’ voices. And though Armacost’s touchingly comic performance and Mortensen’s fierce, nuanced and loving one make their characters come alive, Osborne’s Frank remains something of a cipher.

He’s a perfect blend of confidence and self-doubt, charm and mockery, in his opening monologue. But when it’s time for him to wrap up the story and resolve the contradictions in what the three of them have said, he seems to run out of steam.

To be fair, he’s also burdened with a final sentence that’s less a resolution than a punch-line, which falls flat just like the punch-line of a joke that’s gone on too long. The artists’ desire to return in middle age to a work of their youth is understandable, particularly a work as profoundly retrospective as this.

But that desire can’t overcome a fundamental weakness — whether of script, direction or performance — which leaves the “Faith Healer” audience scratching its head, wondering exactly what all the fuss was about.