From our Passover

By Achy Obejas

From our Passover

By Achy Obejas

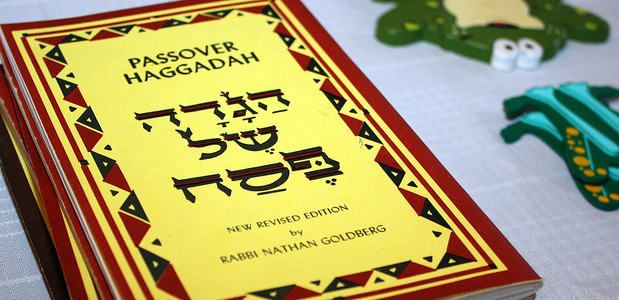

I’ve lost track of how many years we’ve been celebrating Passover in our very religiously and ethnically complicated home. But it’s been ages. Every year, we write a new Haggadah, updating, refining, focusing on a new issue. But as I was sitting down to do this year’s and looking over the many different versions of past years, I realized this particular passage seemed perenial. We borrow from many sources — different poems, different haggadahs, a million internet sources — so it’s hard to know exactly where this began. If we wrote it, great. If we borrowed it, thank you. What we know is, it’s food for thought, and it’s worth sharing.

* * *

One Jewish tradition that we actually think about following every year in preparing for Pesaj is eliminating chametz, or leaven from our house. Traditionally, we would go through our cupboards to remove all products of leavened grain from our possession.

When this task (called bedikah) is accomplished, we destroy a symbolic measure of the collected items by burning (biur), and a blessing is recited.

This reminds us that matzah, the sanctified bread of Pesaj, is made of the same grain as chametz, that which is forbidden to us on Pesaj.

What makes the same thing either holy or profane?

It is what we do with it, how we treat it, what we make of it.

As with wheat, so too with our lives.

As we search our homes, we also search our hearts.

What internal chametz has accumulated over the last year?

What has made us ignore our better angels?

What has turned us from the paths our hearts would freely follow?

Originally, Pesaj was a nature festival commemorating the barley harvest and the lambing season in ancient Palestine; it also marked the rejuvenation of life in general.

Eventually, Pesaj came to symbolize the Exodus from Egyptian bondage, which, although of questionable historical accuracy, meant more than any other “event” in the life of the ancient Hebrews. It was an exhortation to speak out against injustice, to rise up, to cherish freedom as one of the basic requirements of life.

* * *

Whatever you celebrate this weekend, and even if you don’t align yourself with any particular practice, we hope you spend it surrounded in peace surrounded by those you love and in appreciation of all our blessings.

As my cousin from Miami says, happy Easter seder!