Leadership lessons from the Battle of Gettysburg

By Al Gini

Leadership lessons from the Battle of Gettysburg

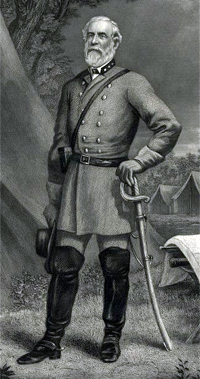

By Al GiniThis week marks the 149th anniversary of the battle between Federal and Confederate forces at Gettysburg, Penn. The outcome of the Battle of Gettysburg, fought July 1-3, 1863, directly impacted the course of American history. Simply put, had Confederate general Robert E. Lee been able either to avoid battle or defeat Union general George Meade’s forces, the outcome of the war could have been very different. A century and a half later, there’s still plenty we can learn from Lee’s missteps.

Although the Union Army beat Confederate forces, in a very real sense, the South helped to defeat itself by making a number of inept and disastrous decisions. In fact, it can be argued that Lee, considered by many to be a military genius, is directly responsible for losing the battle of Gettysburg due to his blatant mismanagement, misjudgment and a combination of arrogance, pride, fear of failure and narcissism.

Many historians believe that Lee’s second-in-command, Gen. James Longstreet, better understood the bigger picture. The Southern Army was in Pennsylvania in an attempt to outflank its opponents, defeat them on Northern soil and possibly turn the tide of the war. Because Lee’s army was smaller than the Union forces, Longstreet wanted to avoid combat. Failing that, Longstreet wanted to choose a different location and fight a defensive battle. But when the Southern Army was intercepted by Union cavalry, Lee felt it was unmanly and improper to leave the field in the face of the enemy, and so he chose to stand and fight.

After the first day of battle, the Southern forces achieved a series of minor successes and Lee ordered a major assault against the Union flank at Little Round Top. The Southern attack was rebuffed and serious losses incurred. At this point, Longstreet advised withdrawal, but Lee felt the honor of both his army and the Confederacy was at stake and ordered a direct assault against the center of the Union lines. The now-infamous “Pickett’s Charge” ended in defeat and slaughter. Begrudgingly, Lee was forced to escape with his now decimated army.

Whether in business, government or war, there are leadership lessons to be learned here. Even brilliant leaders can make bad decisions. Lee lost his focus on the objective of the mission and refused to listen to contradictory counsel. His demeanor made it clear to all members of his staff that he would not deal with counterfactuals and that his wishes were to be followed to the letter. Lee’s early victories gave him a false sense of security both in regard to his general strategy and the strength and abilities of his army. Lee took the battle very personally. He did not believe that the Army of Northern Virginia, which he felt was made up of true believers, could be defeated by a Northern Army made up mostly of conscripts. He did not want to lose to a Union officer corps that he had either commanded in the Mexican War or knew while he had been superintendent of West Point.

In a real sense, Lee’s dedication and devotion blinded him to issues he either disagreed with or did not want to deal with. All forms of leadership must be open to the advice of others, even when they tell us things we do not want to hear. As the story of General Lee demonstrates, myopia can lead to disaster and failure.

Al Gini is a professor of business ethics and chair of the department of management at Loyola University Chicago. He is also the co-founder and associate editor of Business Ethics Quarterly, and the author of several books, including My Job, My Self and Seeking the Truth of Things: Confessions of a (catholic) Philosopher.