On days where the wintry weather overtakes Chicago and you can barely see outside of your window, I’m oddly reminded of the 2000 kids’ movie Snow Day. According to the logic of the film, snow days change things; they re-write the rules. When the snow began to hit in the wee hours of the morning, I poured myself a glass of wine, listened to the new David Bowie and re-posted a photo of the RedEye to Facebook before bedtime. All in all an average night, right?

But I forgot the movie’s lesson: anything can happen on a snow day.

When I woke up Tuesday morning, that photo had been shared from my personal page over 2,500 times and another 600 from the author’s page. I figured that a couple friends of mine would comment on it, and we would privately lament the state of media racism in this country, before we move on to eat sandwiches and poop (not at the same time). I’ve become so desensitized to racism that I no longer am surprised when things like this happen, because they’re such a common occurrence. We want to be newly incensed every time Victoria Jackson says something stupid or people have racist reactions to chips, but at a certain point, these things become the expected norm, yet another dick in the wall

On the evening in question, racism just made me sleepy. Call it

racism fatigue.

However, the photo going viral Tuesday reminded me how much we need this dialogue, how much we need to be reminded that these issues are worth engaging and that we have a responsibility to spread awareness. It reminded me of my own privilege in being able to shut the computer on racism and ignore it if I want to. I can plug my ears and say la-la-la if I want to, because (as a non-POC) structural racism benefits me. On an unseasonably cold March morning, it was the ultimate alarm call. The best part of waking up is racism in your cup.

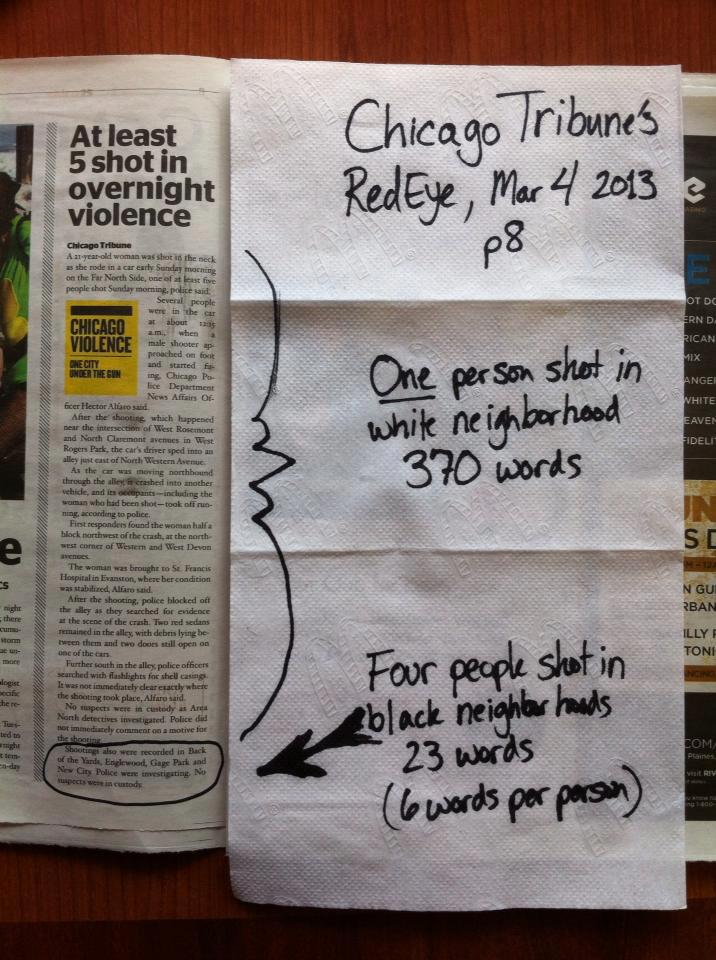

For those unfamiliar, Westgard’s photo breaks down the amount of coverage allotted to crime in Chicago, where the shooting of a woman in Rogers Park gets 10 times the word count of four people killed in the Back of the Yards, Englewood, Gage Park and New City. The

RedEye piece is a abridged version of Adam Sege’s original

Chicago Tribune article, which goes further into the incidents in the latter four neighborhoods. It’s problematic that Sege had to lead with the woman in the Northside neighborhood, burying the others at the back of the article. But at least it’s more equitable. That’s better,

n’est-ce pas?Spoiler: Non.

Is it sad that I could even think about “defending” the Tribune for devoting 50 percent of their content to one North Side woman and the other 50 percent to folks in “black” neighborhoods? Is it sad that we can so easily overlook the fact that the RedEye truncated coverage of everyone not in Rogers Park, deciding that mention of them was all but expendable? Yes, but that’s what it’s come to these days. It’s sad that this is the reality. You can comforting yourself by saying, “Well, at least the RedEye didn’t leave out the South and West Side stories entirely. Those folks got a whole paragraph, 23 words of shiny, abridged, motherf*cking inclusion. Where’s my wine? Let’s get drunk.” Welcome to the fatigue.

In Westgard’s breakdown of the article, he labels Rogers Park as being a “white” neighborhood, which (to an extent) it is. Statistics show that the neighborhood has a larger white population than any other demographic, but Rogers Park boasts Black and Latino statistics that nearly match it, with respective counts of 26.3% and 24.43%. If you’ve ever been to West Rogers Park, you know that the neighborhood is famous for its thriving South Asian scene, with bustling Indian and Pakistani restaurants up and down Devon. You can’t go anywhere without tripping over great South Asian cuisine.

I live in a building that’s half-immigrant and half-white—with Rogers Park’s student population blending with its first- and second-generation residents, populations that overlap just as often as they don’t. But despite this fact, Rogers Park is perceived to be white, with Loyola University getting most of the credit for generating the neighborhood’s energy. Additionally, Rogers Park gets lumped in with the rest of the North Side (often called the “White Side”). Despite enjoying the diversity of everything from Uptown and Buena Park to Andersonville and Albany Park, we stereotype the North Side as a homogeneous Caucasian fantasia, as if Lakeview were the only neighborhood. Even if it’s not the reality, the specter of Wrigley takes over the North. We get whitewashed.

Because of the North Side’s perceived white centrality, we get the coverage that the South and West Sides do not. Last year, I wrote an article on my experiences living in Chicago, an ode to everything I love about the city after calling it home for almost a decade. The piece was

called “40 Reasons I Love Being a Chicagoan,” and it included everything from Big Chicks to Costello’s, whose Mess Sandwich I would eat every day if my heart would allow it. I wrote it from my limited view as a North Side resident, where I’ve lived every year of my residency here.

A number of respondents accused me of “Northsider Bias,” charging that I left out perspectives that were reflective of a larger cultural population. I was furthering the stereotype that Chicago only happens on the North Side. Where was Bronzeville? What about Pilsen? Why didn’t I mention Bridgeport? At first, I was taken aback by the accusation—but then I realized they were right. I’d been to the South Side a handful of times, and it was a faint blip on my cultural radar. This is a common reality in Chicago, where you can barely find a train to take you anywhere past Roosevelt. For Northsiders, it can be difficult to get outside of your niche experience or learn to think about Chicago differently. You get trapped in your own reality.

This ideological infrastructure permeates the ways in which we talk about Chicago and how we live our lives here. When realtors and property agents signify “good neighborhoods,” they aren’t talking about Back of the Yards or Englewood. They wouldn’t even show you a property in Englewood. They mean Roscoe Village. When they talk about neighborhoods that are “up and coming” or “on the rise,” they mean Uptown. In Rogers Park, Loyola has been buying up a great deal of the property in the area. They now own our building. It might not be a “white neighborhood” currently, but it’s slowly getting there. Baby steps.

As a representation of a city that’s heavily segregated, the

RedEye article reflects larger issues of racial inclusion in our city, ones that are so pervasive that they are nearly invisible. It’s a symbol of a media industry that’s equally structurally classist and racist as the city, driven by economic incentives to reach a majoritarian audience of white consumers. The reason I barely blinked at the

RedEye article is that coverage like this is so commonplace. It even has a name: “

Missing White Woman Syndrome.”

Can you name any non-white woman who has gone missing and gotten major press coverage? Rosie Perez doesn’t count, so me neither.

Reason magazine gives us two telling examples of this:

“Remember Laci Peterson, who disappeared on Christmas Eve, 2002? Her case received saturation coverage in the U.S., and widespread coverage elsewhere. You could follow it in the Taipei Times if you cared to. By contrast, Evelyn Hernandez – like Peterson, very pregnant at the time of her disappearance – went missing seven months before Peterson did. Her torso was later found in the San Francisco Bay. The case got a few mentions here and there, but was largely ignored.

“Last summer a jury acquitted Casey Anthony of murdering her daughter, Caylee, in 2008. You remember. Her trial received seemingly nonstop attention across the nation. But as Alexander points out, just about nobody has ever heard of Aja Fogle, N’Kiah Fogle, Tatianna Jacks, or Brittany Jacks. Like Caylee Anthony, those girls – ages 5, 6, 11, and 16 – were murdered in 2008. Their mother was convicted of the crime and sentenced to 120 years in prison.”

The more you read the news, the more you realize that the axiom isn’t if it bleeds, it leads. The reality is that if it bleeds white, it leads. Such framing is meant reach the demographics that media outlets find more attractive as an audience; those with cultural and financial capital get the coverage, whereas less “lucrative” markets are otherized, left out or footnoted. (See: them urbans.)

Although the woman in the RedEye piece’s race was never mentioned, ethnicity is often interpellated as white in news media—as whiteness has become our socioeconomic default setting. Observe any billboard, newspaper, advertisement or magazine. Turn on CBS, our most-watched network. The media is white people. We’re looking at an industry where “white journalists write 93% of front pages in the U.S,” and statistics from 2011 show that just 13.26 percent of journalists overall are writers of color. Hell, I’m white and in the media. I’m part of the problem. I am the man.

Written at the tail end of the Obama-Romney race, a write-up from Salon further addresses this issue:

“The percentage of [front page election] articles written by Asian American reporters is 3.3%, by African American reporters is 2.9%, and by Hispanic reporters is 0.7%. This under-representation of minorities reporting on the front page holds true across most media outlets for most ethnic groups. The Dallas Morning News stands out as an exception where 18.8% of their front page stories were written by African Americans. The most striking under-representation of minorities in our data is that of Hispanic journalists, considering the Hispanic population stands at approximately 16.3% of the U.S. population (according to the 2010 Census).”

Although I’m happy to see the Internet take the RedEye to task over its exclusion of minorities in coverage, this criticism needs to be shared with an entire industry and city that continues to marginalize voices and perspectives of color. The RedEye is such a tiny fraction of the problem that I worry we’re not seeing the forest for the racist trees, but I’m heartened by the RedEye’s timely response to the criticism.

In addition to reaching out to Westgard on Twitter, they released a mea culpa on social media within less than 24 hours of the meme going viral. They didn’t even try to defend themselves or offer excuses for their gaffe. They simply apologized. It’s an incredibly classy move, especially from an outlet often dismissed as tabloid journalism or “fluff.” This response is anything but. Here’s what they had to say:

“The online conversation that’s developing around this story is an important one. Thank you for the comments and feedback. This is incredibly important to us, especially as we set out to shine a light on Chicago violence this year. Conversations like these will continue to inform and improve our coverage. We hope you’ll continue to join us in addressing these issues.”

We can shoot the messenger all we want, but as this statement shows, we must target the system along with them. By releasing this statement, the RedEye has recognized that this is a conversation we need to be having, whether we feel burned out on talking about privilege or our eyes are being opened for the first time by the simplicity of Westgard’s graphic. In this photo, Westgard makes the allegedly invisible plain and clear. The visual brings the discourse to those who might not think critically about structural racism or take the time to check out Racialicious or Crunk Feminist Collective, where these discourses take place every day.

We need to keep in mind that making the RedEye apologize won’t solve racism and remember to take accountability for raising awareness and shining a light on racism—with whatever tools we have available. Racism isn’t just the RedEye‘s problem. It’s everyone’s.

Nico Lang writes about LGBTQ issues in Chicago. You can follow Nico on Twitter @Nico_Lang or the Facebook.