Rolling out the green carpet, legally speaking

By Chris Bentley

Rolling out the green carpet, legally speaking

By Chris Bentley

A business calling itself green is not the news it used to be. That’s due in part to the prevalence of “greenwashing,” but it can also be taken as a sign that the movement to integrate environmental and business values has largely been successful.

Still entrepreneurs with an environmental bent sometimes face a difficult choice: become a corporation and risk compromising core beliefs for the sake of profit, or forgo incorporation and give up the all-important investment dollars that framework is designed to attract.

This month, however, Illinois became the first state in the Midwest to provide those companies another way: 12 businesses in the state have already registered as Benefit Corporations — companies with a stated purpose of providing a positive benefit to society and the environment. Unlike conventional corporations, whose directors are obligated first and foremost to pursue profit for their shareholders, Benefit Corporations take a “triple bottom line” approach, pursuing financial, social and environmental returns. The clothing company Patagonia and Vermont’s worker-owned King Arthur Flour are among the growing number of high-profile Benefit Corporations on tax rolls today.

“The corporate structure lets you communicate to the world that you stand for something,” said Steve Sherman, executive vice president of Chicago’s GreenChoice Bank, which makes loans to sustainable businesses and community-based initiatives. GreenChoice recently became the first bank in the nation to register as a benefit corporation. “Instead of just maximizing the short-term returns to shareholders, you can include other returns to other stakeholders.”

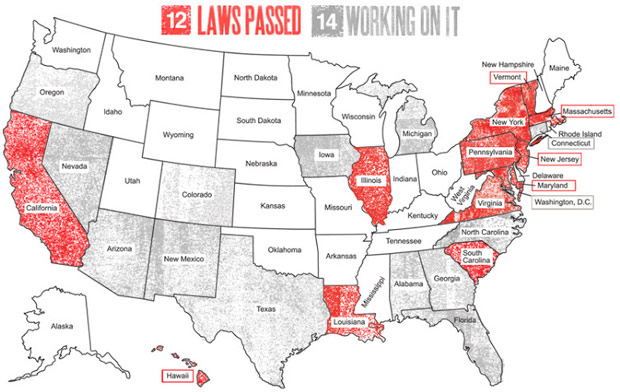

Illinois’ legislation was signed in August and took effect with the new year, adding Illinois to the ranks of California, New York and nine other states that allow Benefit Corporations. More states are expected to take steps toward their own legislation in 2013.

Benefit corporations are required to state their larger purpose in their articles of incorporation, and must publicly report their progress on those goals annually to a third-party certifier. That takes the structure beyond the common corporate practice of “corporate social responsibility,” or the boilerplate company mission statement. It shows that they “walk the walk,” Sherman said. The seal of approval could attract cash from “socially responsible investors,” a sizable and growing group. On the other hand, some lenders might raise interest rates for Benefit Corporations, in part to make up for the uncertainty involved with the extra step of verification.

The new structure also gives a company’s mission a bit more staying power. Say a Benefit Corporation is acquired by a conventionally structured company. The articles of incorporation, which include the benefit corporation’s stated purpose, survive the acquisition.

The socially conscious Vermonters behind Ben & Jerry’s were famously forced to sell their ice cream empire to Unilever, when the international food conglomerate offered to buy them out in 2000. Corporate doctrine and legal precedent made the deal one that Ben & Jerry literally could not refuse — at least when justified in terms other than shareholder benefits. (The brand’s social and environmental mission ended up surviving the acquisition, but at the time its owners did not want to sell.) Had they been a Benefit Corporation, however, they would have had more latitude to consider societal benefits when making business decisions and likely would have declined the offer.

Shareholders are hardly irrelevant in Benefit Corporations. In fact, if shareholders and directors of a Benefit Corporation have believe the company isn’t fulfilling its mission, they can compel the leadership to prove it. If the company fails, it reverts back to being a regular corporation with normal duties to its shareholders. The logistics of such details may have to be worked out in the legal system, which hasn’t yet considered many cases from these new corporate entities.

Some worry the triple bottom line could become a crutch used to justify a subpar corporation’s poor quarterly performance. Profit is still the lifeblood of any private enterprise, however, and underperforming companies aren’t likely to last much longer as Benefit Corporations than they would under a conventional corporate structure.