The Great Loop Flood

By John R. Schmidt

The Great Loop Flood

By John R. Schmidt

Twenty years ago today, Chicagoans got an unexpected history lesson. April 13, 1992 — the day of the flood.

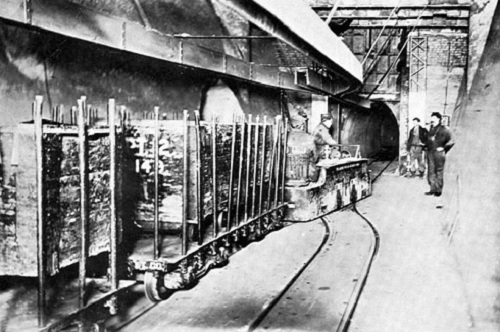

Early in the 20th Century, a network of tunnels was built 40 feet below the streets of downtown

Chicago. The tunnels were used mostly for hauling freight between Loop buildings. They were abandoned during the 1950s.

By 1991 most Chicagoans knew nothing about the freight tunnels. That December, a contractor happened to be sinking wooden pilings into the river at the Kinzie Street Bridge. The work caused a crack in one of the tunnel walls. The city was notified about the accident.

Had a water main broken? That explanation was soon discarded, as the real problem became evident–the river had pushed open the crack in the freight tunnel wall, and was pouring through.

The flood spread southward, into the Loop. Electric and gas lines were knocked out. More basements were flooded. The waters eventually reach as far south as the Hilton.

Trading was suspended at the exchanges. Government offices shut down. Businesses closed early and sent their employees home–but not on the subway, because the power was out there, too. Thousands of people milled aimlessly around downtown, trading rumors.

It was an odd disaster. At street level, everything looked as it always had. Officials assured the public that the situation was under control. Governor Jim Edgar met with Mayor Richard M. Daley at City Hall. Afterward the governor told reporters there was no need to call out the National Guard.

About 11 a.m. the river locks were opened. That let the Chicago River resume its natural course into Lake Michigan. The water in the tunnels continued to rise, but more slowly.

By evening the water level had finally stabilized. Now the cleaning up and pumping out began. It would take weeks. A private contractor finally had to be brought in to seal the original leak at Kinzie Street.

The price tag for damaged goods, repair costs, and lost business was over $100,000,000. For insurance reasons, the April 13th water event is officially classified as a “leak.” But no matter what name is used, those who experienced it firsthand often echo the reaction of their mayor – ”What a day!”