After Water: ‘How do you sleep at night?‘

By Shannon Heffernan

After Water: ‘How do you sleep at night?‘

By Shannon HeffernanAs we looked for writers who would be game for this experiment, we came across Michele Morano. She teaches creative nonfiction at DePaul University and it turned out she was already talking with scientists. We decided to launch our series with the story about those conversations.

It all started when Morano was having trouble sleeping. She would wake up in the middle of the night, thinking about climate change. “I don’t even think I knew enough then to imagine scenarios, I think I just had this blank fear of, what’s going to happen, what’s going to happen to my child?” she explained.

All her 3 a.m Googling wasn’t helping much. But then she tripped upon this online support group for people anxious about climate change. No one was debating politics or policy, they were just genuinely trying to figure out the same problem Morano was trying to solve.

“How do we get through, not even through the global warming, but how do we get through what we are facing right now, which is the kind of knowledge that something awful is coming, but not knowing exactly what’s that going to look like?” said Morano.

This online support group was for everyday people, but Morano started to wonder if the people who study climate change were having these conversations, too. Do scientist feel better because they know more? Or is it scary studying about what could be ahead? So she did something kind of crazy and kind of brave: she called some of the top climate change scientists and asked: What are you seeing and how are you coping?

How it feels to predict the future

Morano thought it would be hard to get the scientists to be emotionally open, but it turned out they were eager to talk. Some scientists said they just did not focus on the future too much, because they had to detach themselves if they were going to keep working to solve the problem. Others said they worried about their children and grandchildren.

Morano says most scientists she talked with did not think we will be able to stop the earth from heating up by at least two degrees on average. As Morano talked with scientists, she started to get a more real idea of what that was going to look like.

Related: What water issues in California mean for the Midwest

Terry Root, one of the “go-to scientists” looking at how animals and plants handle climate change, told Morano that if we get to 2 degrees warmer, we could lose 20 to 40 percent of all the known species on the planet. If we get to 4 degrees warmer then we could lose as many as half.

“Some of them are going to be species that we need. How do we know what species we need ahead of time? We can’t save them all. That’s why I get into triage,” Root told Morano.

Morano said it was comforting for someone to be frank about the harsh situation we were up against, it was also comforting to hear such practical solutions. But Morano says she could tell that Root was also someone who was struggling with the realities.

“I just had a discussion on the phone with my boyfriend about how much longer can I do what I’m doing,” Root told Morano. “I mean all I do all day long is think about how species are going extinct. It is tough. It truly is tough.”

The local take

Morano talked to scientists all across the country. But we wanted to hear local scientists answer Morano’s questions—what were they predicting for Chicago and how they were coping with those predictions. So we joined Morano as she talked to some local scientists.

Related: Will California drought prompt more Midwest agriculture?

Philip Willink is a research biologist at Shedd Aquarium and he took us down to Lake Michigan. He said the lakes are predicted to get warmer and he pointed out species that would thrive in that environment, such as the big mouth bass. But he also told us about species that would struggle in warmer water, for example, a fish called a sculpin.

Sculpins are not the kind of charismatic creature that you’d see in an environmental ad—like a dolphin. It’s brown and grumpy looking. But Willink studies it. It is his brown fish.

He says sculpins are having a hard time because of habitat destruction and invasive species. But climate models show the fish may have bigger problems. The fish likes cool water.

“So do we go through all the effort to save this species from invasive species and habitat loss if it’s just going to be doomed by climate change?” he said.

Willink says studying an obscure and at-risk fish can be a lonely pursuit. But as a scientist he is used to change.

“If we were to go out over here in Lake Michigan there’s the remnants of a forest, because we know at one time Lake Michigan was 50 to 100 feet lower, at one time. So we know over the past several thousand years the waters have gone up and down,” he said.

To understand the kind of long-term changes Willink talks about we went next door to The Field Museum where we met Abigail Derby, a conservation ecologist.

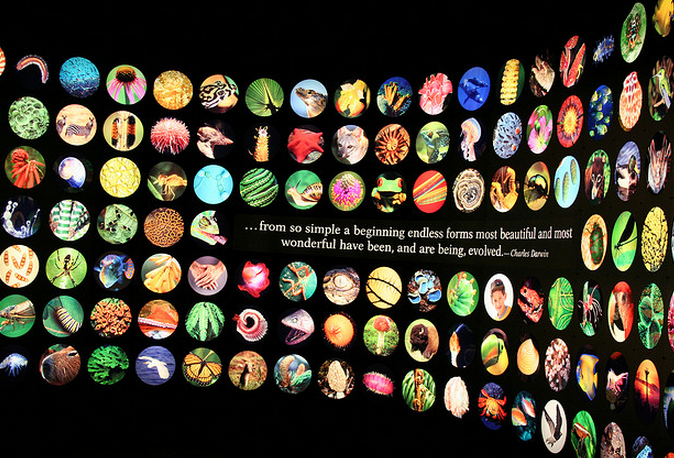

She took us to an exhibit on earth’s evolution. The exhibit covers five mass extinctions, including the dinosaurs. Then at one point, you turn a corner, and you are suddenly in present day—the sixth mass extinction. According to a ticker in the museum, 33 species were estimated to have gone extinct between 8 a.m. and 3:30 p.m. that day.

Derby told us that there are two big differences between current mass extinction and the previous five. The first is the rate: change is happening faster than at any other time we know about in geological history. The second big difference is what’s causing the change; Derby calls this the driver. And this time, it’s us.

“The good news for the driver is we can change that. We can make choices to do something different,” said Derby.

Morano asked her how optimistic she was that we would make the right choices, and make them quick enough.

“I think it depends on the day you ask me,” she told us ruefully. “I happen to work with municipalities to do green infrastructure, and I find that a very rewarding and very optimistic field to be in. There is lots of action on the local level.”

Derby acknowledged that she was not quite answering the question.

“I purposefully didn’t answer whether or not I felt that we would make enough gains in the amount of time needed to reduce the most negative impacts, because I feel in some way if I say out loud, ‘Oh I don’t think that can happen,’ then somehow I am contributing to it not happening. And I don’t truly believe in my heart of hearts that it can’t happen. So I am careful about what I say. Because at the end of the day I want the message to be what you do matters.”

Related: Drought drives drilling frenzy for groundwater in California

There’s research that backs up Derby’s worry. It shows that if you tell people about a possibly terrible future and you do not give them any sense of hope, they shut down.

Scientists worry about that because they want people to act on the research. Morano said almost everyone she spoke to was optimistic technologically and pessimistic politically.

“Over and over again people said, we can fix this. But we’re not doing it. And there’s no indication we will.” said Morano.

One of the reasons for that political pessimism is because of how we think about time.

For scientists who study big changes—the formation of the lakes, species adaptation—it may be easier to think over long, geological stretches.

But it’s a struggle for the rest of us to think even 10, 20 or 100 years into the future.

But that is just what we are up to in a series we are beginning today. We’re focusing on the future of the Great Lakes, in a way that is a little different for us. We have brought fiction writers together with scientists and then asked the writers to create stories set decades from now—when clean, fresh water could be a rare resource.

We want to contemplate the future from a dual lens of science and art. We will be sharing our writers’ stories online and on air over the next couple of weeks. It’s called After Water. We hope you join us.

Michele Morano teaches creative non-fiction at DePaul and is working on an essay about her climate conversations. You can find out more about her work here.

Shannon Heffernan is a WBEZ reporter. Follow her.

***

Front and Center is funded by The Joyce Foundation: Improving the quality of life in the Great Lakes region and across the country.