Are some people hard-wired to take more risks than others?

By Dan Weissmann

Are some people hard-wired to take more risks than others?

By Dan WeissmannFrom the time she was 16, people kept telling Jody Michael she should check out one of Chicago’s famous financial exchanges. She’d be a natural, they said, on the trading floor.

Michaels wasn’t interested.

“I kept saying, ‘No! I don’t want to be around numbers. No,’” she says. “And then one day, a friend who was working at Reuters tricked me.”

The friend invited Michael for a bite to eat…but took a detour.

“Instead of going to lunch, we walked onto the trading floor,” she recalls.

This was the famous ‘pit’ at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange in the old days, before electronic trading. It was crowded with guys in colorful jackets – and they were all guys back then – shouting, waving their hands, literally jumping up and down to make trades. Some of them worth millions of dollars. Non-stop.

“I walked on, I was like, OH MY GOD,” Michael says. “It was competitive, it was fun, it was exciting. And it’s the antithesis, I found out later, of most people that walk on the floor. They walk on the floor, they’re overwhelmed. They’re like, ‘Oh my God – what are people doing?’ And it was a very different experience for me. I really wanted to go and play.”

So what makes people like Jody Michael different? Camelia Kuhnen at Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management has given the question some serious thought. A neuro-economist, she studies what’s going on inside people’s heads – literally – when they’re making financial decisions.

“We get to ask questions that have never been asked before. And you know what? We can even answer them sometimes,” she says with a laugh. “For example: Why do some people take a lot of risks and others don’t? Or: Why are some people confident in their beliefs, and others aren’t?”

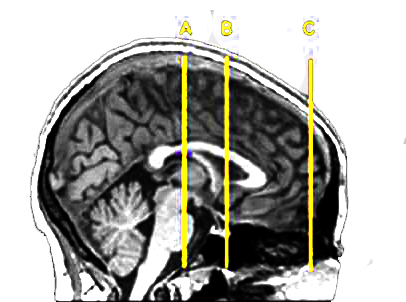

In some experiments, Kuhnen puts people inside fMRI machines, gives them investments to choose from, and sees which areas of the brain light up. She also looks at their genes, their personalities, and their credit reports.

Kuhnen describes Jody Michael’s experience as an example of a phenomenon called “traders’ intuition.”

“It’s probably not gonna be just mathematics – knowing how to deal with numbers and probabilities – that’s gonna make you a successful trader,” she says. “It’s about understanding what everybody else in the market is doing. [Michael] probably was able to understand what all those people in the pit were all doing and talking about – yelling about, I should say.”

In the midst of all that chaos, Jody Michael was able to “read” people, and the room as a whole. Researchers have found that this traders’ intuition is tied to what psychologists call “theory of mind”: The ability to form a mental picture of other people’s thoughts, feelings, and intentions.

Michael agrees. “It wasn’t about numbers at all,” she says. “It was driven absolutely by feeling – ooh, it feels like I’m at home, in the competitive environment and driven by the opportunity.”

The beginning of Jody Michael’s life on the trading floor provides a window into the psychology of traders. And as it happens, when she left the floor 15 years later it was to go back to school to study psychology. Now she’s a professional coach to traders. She says she aims to help her clients understand themselves as well as they understand the markets.

“The most important piece of trading is you,” she says. “As we go into trade, we are shaped by our perceptions, our attitudes, our beliefs, our values, how we think, the moods that we’re in, all of that impacts what we see, what we don’t see, what we take action on, what we don’t take action on. That is the psychology of trading.”

And her best example of the psychology in action is a client we’ll call “Steve.” Steve isn’t his real name because of client confidentiality, but his story opens up questions about the nature of risk taking. How much of it is hard wired in our brain, and how much of it is what we choose?

Steve is a hotshot trader – experienced enough to play the market by intuition.

“He’s a sensation-seeking, I-need-a-lot-of-variety kind of guy,” says Michael.

But, when he first came to Michael’s office, he wasn’t making as much money as he wants.

Michael’s work with Steve takes a few steps: First comes awareness. She helps Steve understand that although he thinks he’s just doing one thing all day – trading – he’s actually doing it in two completely different ways.

First are the setups: As Michael describes it, this is based on long years of experience. When certain conditions come up, bam! He buys this or sells that, and it’s gonna make him a ton of money.

But they only appear every so often, and meanwhile, he’s trapped watching the screens, waiting.

“And he gets bored!” Michael says. “So in between those trades, when he’s sitting around – and this is where he gets into trouble – he will just play, going in and out, all day long, to fulfill that need for that feeling: He’s in it. He’s in the game. He needs to be in the game.”

Camelia Kuhnen’s research shows that some people are just like this – they’re born risk takers. She points to a gene called DRD4 that regulates dopamine levels in the brain’s reward center.

“Yeah, if you carry the long version of DRD4, you tend to take about 25 percent more risk in your portfolio than other people,” she says.

Jody Michael works with Steve for months, and helps him become aware of the difference between the good trades and the other stuff. She has him practice, training himself to do the opposite of what his instincts tell him. If his brain says ‘go,’ Steve learns to stop.

But then Steve starts to falter. He can’t stay disciplined in controlling his trading habits.

“What we figured out with Steve was that he had a competing commitment,” says Michael. “Steve has a strong need to have fun, and play.”

In other words, he was making all these dumb trades because he loved to do it. Or, you could put it this way: He wasn’t just yielding to a compulsion to take risks: He was indulging a desire to have fun – which for him involved taking risks.

Once he knows the difference between work and play, he gets to choose. And what Steve decides is: He wants to keep playing.

“He acknowledged, ‘You know, I don’t care: I love this,’” says Michael. “‘I just wanna do this.’”

So rather than change what he does, Steve changes his attitude. He learns to embrace it.

“What’s interesting is that Steve came to me to minimize the risk and to become a better trader,” says Michael. “And how he ended up leaving was: He was the same trader but at peace with it.

He makes less money than he might – but enough that he gets to keep playing. And enough that he can fly to Vegas eight times a year, with money to blow.

Jody Michael says other traders she’s worked with would never make the choices that Steve does.

“They’re going to look at the dollar amount and say, ‘Hey, percentage-wise, this is crazy,’” she says. “But you get a guy like Steve, and he makes enough, and he says, ‘I’m driven by opportunity, but I also want to play.’ And he does.”

So what does Camelia Kuhnen’s science tell us about what makes Steve so unique? Well, not much. He probably carries the longer DRD4 gene, but genes only account for around 35 percent of behavior, she says. They’re just hints, really, about the kinds of risks you might accept.

“Just the pure genetic component, while it’s important, is not the only thing that drives behavior,” she says. “Your own experience matters a lot. Where you were born and how you were brought up matters a lot.”

And, Steve might say: How well you know yourself, and what you choose to do with that knowledge.

Dan Weissmann is a reporter for Marketplace. Follow him @danweissmann.

“At What Cost?” is made possible in part by the John A. Wing Society, an initiative of the Illinois Humanities Council to improve dialogue about business and the common good.