Belonging in Chicago

By Jessica Young

Belonging in Chicago

By Jessica YoungIn 2008, when I moved in with my husband, it was important to find a diverse neighborhood. He suggested Lincoln Park, and I shot this down swiftly. Lincoln Park was too full of uptight white folks, I argued: with their Starbucks travel mugs and their jogging strollers and their nouveau-riche, douchebag-mobiles. No way, no eff-ing way, am I moving to Lincoln Park.

I know now that my vitriol was grounded in defensiveness and fear. The real reason I didn’t want to live there, and still don’t, is because I feel like I don’t belong there. I get off the Red Line at North and Clybourn and walk past the Apple Store toward the second-largest Whole Foods Market in North America, and I don’t see a lot of black women like me. The Lincoln Park yuppie set doesn’t pay me a lot of attention, but I’m not among my people. I might be more at home in Bronzeville or the South Loop, where sistas with locs and head wraps are common. But Lincoln Park is not my hood.

***

“Belonger” is a word used frequently in Caribbean countries associated with British Overseas Territories. Belongers are the descendants of African slaves, whose ancestors were brought to the islands to work the salt ponds and cotton plantations. This land was built on their backs so it belongs to them. The Turks and Caicos Island Immigration Board legitimizes this term. Belonger status gives you residence rights, the right to vote, to own property, and to run for office. It isn’t easy to get, and it doesn’t give you citizenship; but it does set you apart from the 300,000 tourists who besiege the island every year.

The word “Belonger” has a strong sense of ownership. I try to imagine what it would look like for America to have Belongers. What if our country had a powerful citizenship standing that was guaranteed to those of us who had their ancestors hauled here under slave status? What if ancestors of First Nations people who were disenfranchised by European settlers had status that gave them privilege in their home country? Who would the Belongers in America be?

***

Number of Chicago area neighborhoods my husband and I have lived in, single and married: nine. Him: Lakeview, Lincoln Park, Edgewater; Me: Evanston, Humboldt Park, Uptown; Us: Lincoln Square, Rogers Park, South Loop.

Number of races represented in our home: two. He’s American-born Chinese; I’m black.

***

I learned recently that dharma isn’t just the name of a cute blonde on a 1990s CBS sitcom; it’s a Sanskrit word that means sacred meaning of one’s life. Destiny. If such a thing is real, not just the stuff of romantics and fortune tellers, then Chicago has been my dharma for a long time. Chicago drew me to its center at an early age; I’ve lived here for more than ten years. It’s the kind of city I like: sophisticated, diverse, but without the hard-edged ambition of the East Coast or the superficiality of the West Coast. Despite my happiness, I often long to move to a city less segregated, with a healthier local government, and with better winters. But I can’t actually seem to leave. My belonging here feels like a kind of inertia. I wouldn’t mind feeling so stuck if I only felt sure I belonged here. As a black woman in an interracial marriage, I want to find a community that looks like my family. That’s hard to do; there are still shops where my husband and I get the double takes by clerks, restaurants where we’re given the table in the back. I wonder if we might feel more comfortable in other cities. But I can’t leave. I’m a refrigerator magnet glued to the Whirlpool icebox of Chicago. Maybe what keeps me here isn’t cosmic dharma, but it’s the stasis of having lived in the Midwest almost all my life.

***

For as strongly as I feel I don’t belong in Lincoln Park or Lakeview — neighborhoods I ignorantly dismiss as “white”—I also feel like I don’t belong in some “black” Chicago neighborhoods either. When I spend my time and money in Hyde Park or Chatham, Austin or Lawndale, locals can tell I’m not from down the street. Maybe it’s the clothes that give me away: even some white friends have called me preppy. In an interview with Michele Norris, writer and cultural critic Touré defined post-black brilliantly: “Post-black is talking about people who are rooted in blackness but not constrained by it. They want to be black. They want to deal with the black tradition, and the black community, and black tropes. But they also want the freedom to do other things.” I am liberated by this idea; I can wear J. Crew and do yoga and eat vegan, while still appreciating musicians Jill Scott and All Natural. But where can I live? If I choose a black neighborhood to be with my people, will I catch static as the resident Oreo on the block? If I choose a white neighborhood to avoid intra-racial friction, will I be alienated by people with no context for my life experience? It may be that there are all kinds of black; but I’m not always sure if the bandwidth in Chicago can accommodate these different kinds of black. Segregation reinforces stereotypes of the self and others. As much as I love the Second City, I’m not sure if its citizens are broadminded enough to grow willingly into a city that is beautiful with diversity, and not pockmarked by racial singularity.

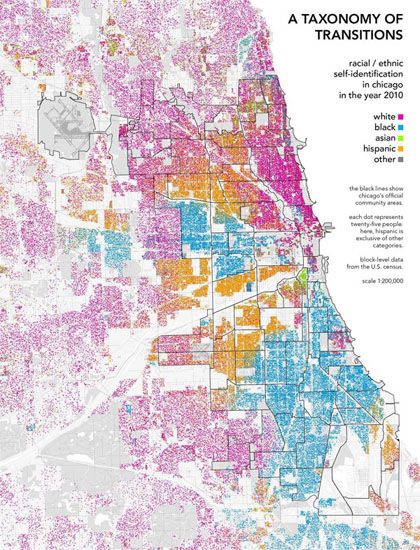

Bill Rankin’s “A Taxonomy of Transitions” map shows that the racial lines that divide Chicago are more permeable than they often feel to me – more like cellular walls and less like cinder block walls. I’m pleased by this. But I’m still looking for the neighborhood in Chicago that’s populated with all kinds of multi-colored dots. If ever I find that place, it’s where I will know that I belong.