‘Devastating’ bat disease reaches Illinois, scientists report

By Chris Bentley

‘Devastating’ bat disease reaches Illinois, scientists report

By Chris Bentley

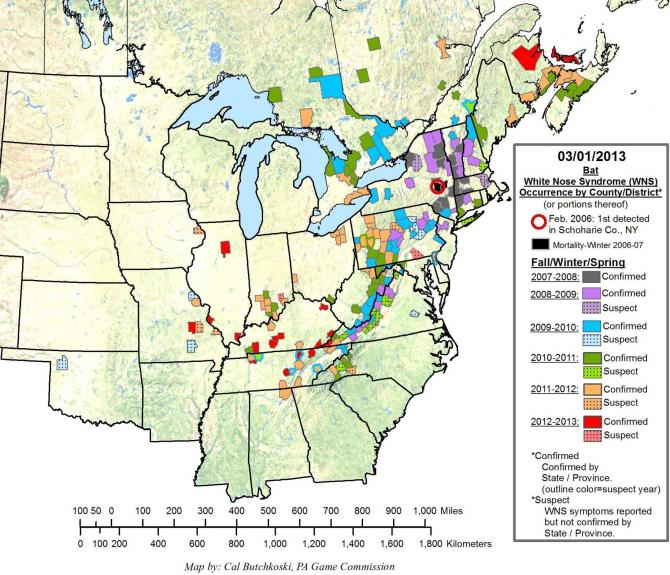

Scientists have confirmed the arrival of the fungus known for causing White-Nose Syndrome, a disease blamed for more than 5.7 million bat deaths since its discovery in 2006.

“It’s devastating news,” said Julia Kilgour, a bat ecologist with the Urban Wildlife Institute.

Its arrival was predicted years ago, in light of the disease’s unrelenting march through bat populations as far west as Oklahoma and as far north as Québec. Some infected caves on the East Coast have lost 90 to 100 percent of their population of little brown bats, a species also common in Illinois.

Perhaps as troubling as the disease’s severity is how little scientists know about its pathology.

“This disease has come up so quickly and spread so rapidly that it’s very difficult for scientists to keep up with it,” Kilgour said.

The name White-Nose Syndrome describes the fuzzy white fungus that accumulates on the noses of infected bats, but also on their wings, ears and tails. One prevalent hypothesis for how it affects its host is that it interrupts the bat’s hibernation cycle. Irritated by the infection, bats rouse from their winter rest too frequently, burning up fat stores meant to carry them through lean winter months.

The disease also destroys skin tissue on the wings of infected bats, dehydrating the bats and leaving them with holes sometimes as large as an inch in diameter (the typical little brown bat wingspan is less than 10 inches). Scientists have not been able to determine whether the hibernation disruption, dehydration, or something else entirely is chiefly responsible for the disease’s massive mortality.

Bats flock together from hundreds of miles around to hibernate, potentially spreading the fungus across state lines. And while humans cannot contract the disease, they may unknowingly ferry it between hibernacula, the scientific term for hibernation locations. White-Nose Syndrome has prompted cave closures and outright bans on spelunking in some areas, and Kilgour said cavers should disinfect their gear with bleach solution or Lysol before entering a new cave.

The fungus Geomyces destructans was first found afflicting U.S. bats in Schoharie County, N.Y., near the state capital Albany. But G. destructans is native to Europe, where it does not seem to cause the disease. Bats that migrate to Mexico or the southern U.S. can escape the cold-loving fungus.

Bats are responsible for perhaps billions of dollars worth of agricultural services each year, by way of pest-control and pollination. Although research done in 2010 by New York state’s Department of Health suggested antifungal drugs already used to treat people and animals, the logistical difficulties of treating millions of bats in the wild are prohibitive.

“Sterilizing nature is not really an option,” Kilgour said.

Although the fungus is here, widespread bat fatalities typically don’t happen until a year later.

Kilgour runs a project attempting to take stock of Chicago’s bat population. Outbreaks like White-Nose Syndrome underscore the importance of wildlife monitoring programs, she said, because they provide a benchmark for future population losses.

“We’ll be listening this summer,” she said.