Ex-felon informs formerly incarcerated of right to vote

By Yolanda Perdomo

Ex-felon informs formerly incarcerated of right to vote

By Yolanda PerdomoIn a back corner at a Chicago McDonald’s, Marlon Chamberlain sits and goes through papers under a movie poster. It’s from the film “The Hurricane” the true story of Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, the famed boxer turned prisoner right’s activist.

There, Chamberlain meets those recently incarcerated who want a new start. Chamberlain is with FORCE, or Fighting to Overcome Records and Create Equality. Chamberlin’s job is to talk to ex-prisoners about everything from how to get a job to how to become a community leader. Part of his work includes talking about his past. Specifically the events leading up to September 2002.

“I have a federal offense. I was arrested with conspiracy with intent to distribute and sentenced to 240 months,” says Chamberlain. “With the Fair Sentencing Act, I ended up serving 10 and a half years.”

He was in federal prison when Barack Obama was elected president in 2008. Chamberlain remembered watching the event and cheering along while the other inmates. But even then, the political process that moved Obama to the presidency was something Chamberlain didn’t care much about.

“I didn’t believe voting mattered. I didn’t see how things could be different or how the mayor or certain state representative could change things in my community. That connection wasn’t there.”

After his release, a FORCE member talked to Chamberlain at a halfway house. That’s when he started to understand that local lawmakers and not the president decide whether money gets allocated to ex-offender programs and how sentencing guidelines are outlined.

Chamberlain also learned that ex-felons could vote. In several states, if you’re convicted of a felony, you lose the right to vote. Permanently. But in Illinois, an ex-offender can vote upon release. Chamberlain didn’t know that. He says lots of people with records don’t know that either. Which is why now he’s working overtime to get the word out before election day.

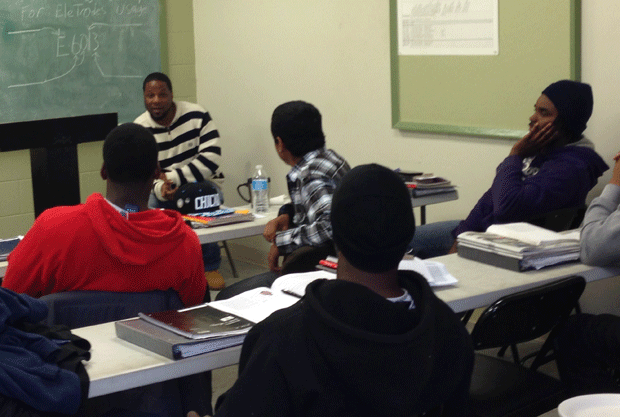

Tucked away between a dead end road and railroad tracks on the city’s southwest side, Chamberlain meets with a group of men from the Chicagoland Prison Outreach. They’re in a work study program and Chamberlain visits with them on Thursdays. It’s part classroom, part bible study and part welding work study. Chamberlain starts the discussion by asking ‘When was the last time anyone voted?’

One person pipes up and says he voted while in jail. He too was told he couldn’t vote, but while in the Cook County Jail, inmates awaiting trial can vote. They’re given applications for absentee ballots. This year, the Board of Elections processed tens of thousands of new applications. Many inmate applications are rejected, mainly because addresses can’t be verified. Out of the more than 9,500 inmates requesting ballots, around 1,300 were deemed eligible.

A person who goes by the name of Kris says even though he can vote, he’s not interested.

“I never cared who was in office,” says Kris, “I wouldn’t even know who to vote for.”

The class tells him he needs to do some homework to know the candidates’ platforms. Chamberlain echoes the notion of doing a little homework and cautions the class about political stereotypes. Like that all African Americans vote the Democratic ticket.

“Because you got Democrats who won’t do nothing. I don’t believe in befriending politicians. You know, no permanent friends, no permanent enemies,” says Chamberlain. He points to the very room they sit in as a result of some kind

of political action.

“So what would happen if people don’t vote for the elected official who signed off on this? Then this program goes away,” Chamberlain notes. Kris does not care.

“All I see is a lot of squad cars coming around. Our neighborhood, how it was in the past, it was better than how it is now,” says Kris. “ At least we had stuff we could do. We didn’t have to stand on the block to have fun. We actually had places.” Chamberlain asks Kris if he’s ever spoken to his alderman about the problems he sees. Kris shrugs, admitting he’s never bothered to make contact. “The city is so fou-fou right now. The city ain’t right.”

While most people heard a person complaining about problems, Chamberlain heard someone much like himself. A person aware of problems, who knows things could be better. Back at the McDonalds, Chamberlain meets up with FORCE worker Teleza Rodgers. She too, is an ex-felon and covers the city’s North Lawndale neighborhood. They talk about how hard it is to get ex-felons motivated to vote. Especially since many of them live the misconception that their voting rights were taken away from them when they went to prison.

“People who don’t know us are making decisions about our lives or livelihoods and our neighborhoods. They don’t live where we live at,” says Rodgers. “They (ex-felons)

tend to have an ear to that. I say we can’t expect to have anyone do anything for us if we’re not doing it.”

Rodgers says there’s no way around the impact of voter representation. And that several questions on November’s ballot can directly impact ex-felons and others in Chicago. Like whether the state should increase funding for mental-health services, whether a school-funding formula for disadvantaged children should be reset, and whether to increase the minimum wage.