For Pakistani attorney, social revolution should sound sweet

By Odette Yousef

For Pakistani attorney, social revolution should sound sweet

By Odette Yousef

“There is a reality of a certain backward mindset which we have inherited, and which we have not yet changed,” says Kazim, “and which we have to change.”

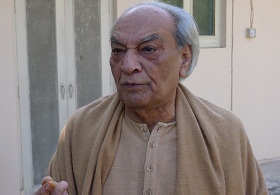

Despite his professional and financial success as a lawyer, Kazim’s lifestyle appears to the visitor to be utilitarian. At home, Kazim wears a simple brown, cotton tunic and pants, with a light scarf thrown over his shoulders for warmth. The house itself is a sprawling, villa-like manse that has been repurposed from a lavish home into a buzzing hive of activity. Off the green courtyard in the center, there’s a room where goggle-wearing men crouch over whirring machines, creating electronic components. In another room, craftsmen cut wood, join together pieces of dried gourds, and polish new musical instruments. There’s a darkroom that Kazim and some students use for their photography. And then there’s the room where Kazim joins us: a fully-padded space on the upper level. Here, one of Kazim’s daughters and some other workers demonstrate for us the sonic power of a stereo system developed in the walls of this house. Rich, resonating tones from both Eastern and Western tunes suffuse the space.

The music turns off as Kazim comes into the room and settles on the floor with us. He explains why, when he could so easily have enjoyed his success in luxury, he’s instead turned his home into a hub of work, sound, activity and, in his own way, social activism.

Early political ideals

Kazim explains that he spent his adult life pursuing what he calls a renaissance for Pakistan. “I felt that we should take a second look at man,” he says, “and see if it is possible for human nature to be more dynamic than it has been, to be more productive and creative than it has been, using that knowledge.” Kazim’s hopes were high in 1947, when Pakistan split from India to become a new, post-colonial nation. He was 18 at the time and wanted Pakistan to become a modern country, one where people could soon use education, justice and technology to achieve their potential.

“So I joined the Communist Party,” says Kazim, “and bought the Marxist theory and analysis as the best toolkit for changing society, and I gave everything that I had to it.”

Kazim says he realized that ordinary people need to challenge themselves to learn new things and achieve new goals if they are to break out of old living habits. He dropped the crusade to change Pakistan’s political system, and adopted a new philosophy. “My position was that unless our people change substantially, you are not going to have changes in government, or policy, or things like that,” he says.

Social change through sound

It took Kazim decades to formulate a new approach to social change and cultural advancement. He eventually settled on the founding of the Sanjan Nagar Institute of Philosophy & Arts in his own home in 1995. Funded by his earnings as a lawyer, Kazim has been using the Institute to explore discrete personal interests: photography, musicology, audio equipment engineering and a new field of study he termed “mentology.” To Kazim, each of these fields presents an opportunity to propel innovative thinking in the arts and humanities, and he hopes ordinary Pakistanis will play a role in those advancements.

From looking at the impressive array of mixers, amplifiers and speakers in the room where he speaks to us, it’s clear that Kazim’s work in the field of audio engineering is the Institute’s most successful effort yet. Remarkably, Kazim entered the field with no related training or education.

“I was looking at the world outside Pakistan,” Kazim says. “Now there, I felt that there was a problem, a genuine problem, in the audio area. After the Second World War it had taken a very strong tendency toward Hi-Fi, toward a mechanical view of sound.”

Kazim hired a math tutor for his team and equipped the Institute with computers and internet access. “So they’re connected, and this is a gift of the times we’re in,” says Kazim. “It’s a question of putting that gift to use, a practical application. So this is a model of how people who’ve been stagnating for a long time, if they connect to the times they’re living in, and its specifics and potentials, perhaps something can be done.”

The team worked in Kazim’s house, developing nearly every aspect of the system from scratch, from the capacitors that moderate electrical current, to the polished wood shells that encase the stereos and amplifiers. Kazim concedes, “We had to have a tough learning curve because none of us were engineers, none of us had experience. That was a rather deliberate decision, because the people we are going to depend upon for some time to come will be our lower-middle class.”

The team created 21 prototypes of the Bhulley Audio System and has earned more than 500 patents. One key innovation: the inclusion of water tubes inside the speakers to mitigate excess reverberations, keeping the sound from getting muddy.

British sound experts audited the Bhulley system and gave it top marks, but Kazim says that’s not the point. “It’s not about music,” Kazim says emphatically. “It’s about these men, they manifestly have had to change themselves in the process, in their hearts, and in their heads,” he says.

Kazim now speaks of the line of audio equipment as a parent might speak of a grown child who must leave home. “My intention is now, as this matures, to separate this from the Institute,” sayd Kazim. “It’s a finished product, and it’s a line of products. It includes the mixers, it includes mic amplifiers, it includes AD/DA converters. So we’d like to make it a commercial corporation apart from the Institute.”

He says he hopes to interest foreign investors invest in large-scale production of the Bhulley system, and that they would employ the men who helped to create it. The more important point for Kazim is whether this experiment, of challenging and supporting ordinary Pakistani laborers to achieve world-class standards, might be replicated elsewhere. “This was really a prototype, which could release their potential, their capabilities, change their motivations,” says Kazim. “They changed themselves, of course, by challenging them(selves).”

Improving an ancient instrument

Kazim’s institute has also won recognition for its work in reviving traditional South Asian classical music through the invention of new musical instruments. In a workshop on the lower level of the house, Kazim introduces us to craftsmen who make the shruti bahar, a relative to the well-known South Asian stringed instrument called the sitar. While the conventional sitar uses a single dried gourd as its resonating chamber, Kazim’s craftsmen piece together sections of several gourds to create chambers with fewer distortions and better resonance. The bridge that the strings sit on is also made from pure silver, which, Kazim believes, conducts string vibrations more effectively than conventional materials.

(Noor Zehra performs on the Sagar Veena.)

Kazim says he’d like to see the Institute’s innovative spirit spread far and wide, and he thinks there could be payoffs for people who’ve never been inside the Institute’s walls. Specifically, he wants the Bhulley Audio System and musical instruments to draw people to Pakistani music and traditional culture, all the while challenging ordinary citizens and providing them with a practical necessity — jobs.

“The point was that if we learn to do productive work, and can earn our living, an honest living in today’s times, then other things will follow,” Kazim says, “then a different approach to society, a more positive approach to the problems of having a society. And that alone would impact upon our politics.”