How do the reversible lanes on the Kennedy Expressway work?

By Jennifer Brandel

How do the reversible lanes on the Kennedy Expressway work?

By Jennifer BrandelMike Cunningham lives in downtown Chicago and works 21 miles away in Northfield, a northern suburb. Unlucky for him, his commute via Interstate 90/94 (the Kennedy Expressway) can last up to an hour and a half. By spending so much time on the Kennedy, Cunningham says he has plenty of opportunity to ponder the Expressway’s two enigmatic reversible lanes. He asked Curious City:

“What’s the logic behind the reversible lanes on the Kennedy? Has the idea worked?”

Turns out the answer to the first question is relatively straightforward, but the whole “has it worked” part deserves some nuance.

So, what’s the logic behind the reversible lanes?

There’s a story behind this, and I got some help telling it from transportation historian Andy Plummer, who served as deputy executive director of the Chicago Area Transportation Study. He also happens to be part of a Chicago transportation dynasty; his father was the superintendent of the Cook County Highway Department in the 1960s.

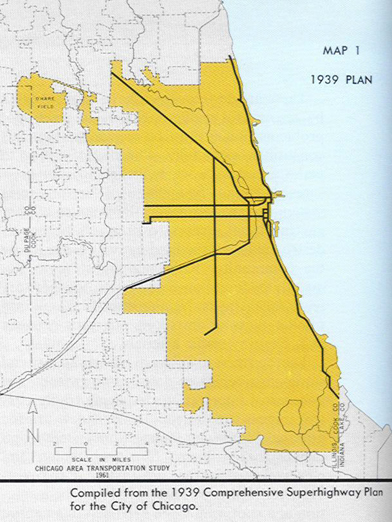

Plummer gets us started by going back to the 1930s and 1940s, when the entire Illinois Highway System was first being conceived. He says the Kennedy’s designers pulled from a familiar playbook, basically bringing the idea of reversible lanes from a system that was already in place on Lake Shore Drive.

“They had hydraulic lifters that basically took the eight lane configuration and in the morning it had six lanes headed downtown and in the evening it had six lanes headed north,” he says.

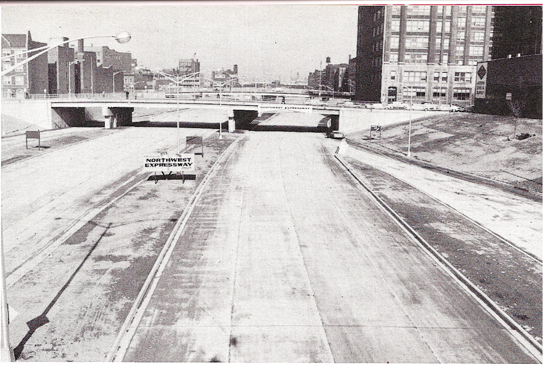

The hydraulic lanes on the drive got a lot of notice because, among other things, they were the first or their kind in the country. Eventually, though, they stopped working so well and — after they became a safety problem — were removed in the late 1970s. But, Plummer says, they served as inspiration for the reversible lanes of the Northwest Expressway (renamed the Kennedy Expressway shortly after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy).

But Steve Travia, the Bureau Chief of Traffic for the Illinois Department of Transportation, says that trend hasn’t continued.

“It’s a very blurry line,” he says. “There is a significant reverse commute. It causes some trouble because the traditional commute, although still very heavy, is catching up. And what may have been a very obvious line 20 or 30 years ago is no more, and we have to be very conscious of that to make sure the reversibles are going the right direction.”

The Kennedy, like commuters, has a schedule

The schedule still favors suburban commuters heading downtown during weekday mornings and heading back out in the evenings. Since 2010, the scheduled target time for a weekday switch of inbound to outbound is 12:30 p.m. Overnight, the lanes are flipped back for the morning commute.

But Guy Tridgell, spokesman for the Illinois Department of Transportation, says the schedule can be changed based on crashes, unusually high travel times or other incidents and events that affect traffic flow on the area’s other expressways.

“In the afternoon rush, if the inbound direction has significantly higher delays, we do consider flipping the reversible lanes back,” Tridgell says. “This would usually be considered after most evening commuters have left downtown and outbound congestion has dissipated.”

The reversible lanes flow with the higher volumes about 80 percent of the time.

Motorists using the lanes might understandably be miffed if it appears traffic is heavier in the opposite direction of the reversible express lanes, but ComCenter supervisor Andy Thompson says those drivers “aren’t seeing the big picture of what we have to assess in here.” The traffic system works like a circulation system. If one vein is clogged, the others are affected. So sometimes IDOT needs to keep the reversibles open in one direction due to traffic on the nearby Edens or Dan Ryan Expressway.

Julia Fox, an IDOT traffic engineer, says the effects of reversing lanes reverberate throughout the system and, were the lanes not open going outbound at the right time — say, during the afternoon rush hour — downtown traffic would be in total gridlock.

How the lanes work

Back when they were first installed in the 1960s, reversible lanes were flipped manually, an operation that required a lot of manpower. There were barricades that needed to be physically moved each time the reversal happened, and there were limited access points to get on and off the lanes. In the early 1990s, though, a substantial redesign automated the lane reversals, bringing the process’ time down to as little as 20 minutes.

The video we made captures the process, but also reveals what can sometimes go wrong.

Does the logic still hold?

To start, we got the take from someone who witnesses and tracks their effects everyday: Sarah Jindra, WBEZ’s former traffic reporter. She says the lanes continue to help the traditional morning and evening commutes.

“When you’re driving, you may not think they’re very effective because you’re sitting there and you’re seeing: ‘Oh, those cars next to me aren’t moving. I’m in the express I’m supposed to be going faster. What’s going on?’ And you may not think they’re very effective,” she says. “But, as soon as you see when they close them and flip them the other direction — how it impacts traffic — it is so effective to have them.”

Jindra says she sees travel times on neighboring roadways change dramatically as soon as the lanes are flipped.

Plummer says the lanes still work well and play a vital role, but he reminds us that they simply were not designed with today’s traffic in mind. Roads get congested enough that cars hit what engineers call “break down,” engineer-speak for stop-and-go traffic and its mix of red lights and red faces.

Plummer says when the Kennedy first began to break down “it used to break down for 30 minutes, 45 minutes. Now, you know, if it’s breaking down it’s broken down for hours because of just the sheer amount of people that are trying to use the same space.”

Is there a fix?

Mike Cunningham was gracious enough to come forward with a question born out of his frustration with his commute. We figured, as a bonus, we should double-check to see if anyone’s thinking through the next solution, one that takes us beyond the Kennedy’s system of reversible lanes.

Plummer reminds me, though, that this had already been thought through. He says, “When they [the reversible lanes] were designed, they were designed as part of a system, and one of the biggest chunks in the system doesn’t exist: the Crosstown Expressway.”

This ghost of a highway was intended to run North-South on the city’s West Side, and the idea was to let a good chunk of traffic bypass downtown entirely. The Crosstown Expressway was never built, Plummer says, because by the time officials were in a position to build it, “the expressway boom was kind of over and the buds had kind of wilted in terms of people’s acceptance of expressways.” Highways split neighborhoods, displaced residents, wrecked historic districts and quickly became a complex hot-button no politician wanted to push. That situation hasn’t changed all that much.

Moving forward, the options for dealing with the incredible traffic on Chicago highways would likely take some creative thinking. Various agencies are looking to new ways to manage highway lanes as well as better and extended public transit options. For now, though, that small 6.2 mile stretch of reversible highway lanes on the Kennedy will keep exerting some control over a relentless tide of cars and trucks.

To hear more about the lanes, check out this debrief from the Afternoon Shift with Steve Edwards: