How to build a better ditch. No, really.

By Robin Amer

How to build a better ditch. No, really.

By Robin Amer

Andy Ward remembers the day he drove through the Darby Creek watershed – the day that convinced him to build a better ditch.

It was the mid-‘90s, and the 560 square miles of Ohio land that feeds in the Big and Little Darby Creeks was one of the most diverse aquatic systems in the Midwest. Ward, a professor at Ohio State University’s College of Food, Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, wanted to know how he could best protect the creek and its tributaries from farm runoff and other pollution that threatened life in the waterways. In excess, chemicals like phosphorous can lead to a massive overgrowth of algae, choking off other plant and animal life in and around the Great Lakes and as far south as the Gulf of Mexico.

As Ward and a colleague drove past some of the local farms, they debated the merits of buffer strips – areas of soil and vegetation meant to separate farm fields from the surrounding landscape and absorb runoff. “Buffer strips were the new thing on the block at the time,” Ward explained, and farmers were being offered financial incentives to build them.

But what did that matter, Ward wondered, if most farmers also used a series of underground drains to draw excess water away from their crops? If the drains ran under the fields they would also run right underneath the buffer strips.

“How much value [were they] really going to provide,” Ward asked, “if a good portion of the flow went right underneath them?”

The farms’ underground drains would often empty into ditches – some as big as 15 or 16 feet wide – that ran around the fields and fed into the watershed. As Ward and his colleague rounded a corner, they saw a bulldozer clearing out one such ditch, ripping out giant clumps of grass and other vegetation and mounds of sediment that had built up over time, fed by nutrients and run-off water.

Ward was shocked. “That’s crazy!” he recalled telling his colleague. “We’re providing incentives to grow grass at the top of the ditch, yet a lot of the flow is going underneath that grass. Then we’re paying people to rip out the grass where the water is actually ending up! It just made no sense to me,” Ward said.

Farmers needed ditches to catch excess water and move it away from crops. But was there a way to design a more environmentally-friendly ditch?

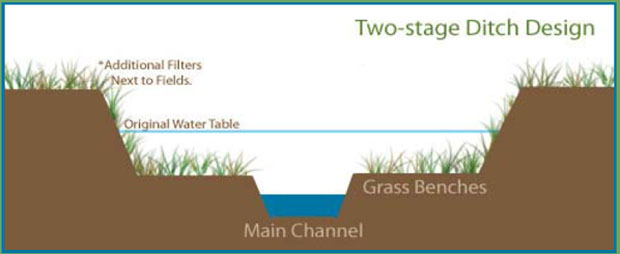

It wasn’t just a crazy dream. Ward and his colleagues came up with what they called a two-stage ditch. Whereas a conventional ditch is a narrow, muddy, waterslide of a tube, channeling water and all of its contents straight through to larger streams and rivers, the two-stage ditch looked like an overgrown series of large steps. Water would flow through the narrow bottom of the ditch, but a flat “bench” of soil above the water, planted with grass and other vegetation, would absorb water and act as a flood plain during times of heavy rain. Rather than fighting nature, Ward figured they could let nature help protect itself.

But what would the farmers and landowners think? According to the environmental advocacy group the Nature Conservancy, at $10-$12 per linear foot, two-stage ditches are vastly more expensive to build than conventional ditches, which cost only $1 to $1.50 per square foot. But two-stage ditches are expected to last a lot longer (around 30 years). The Conservancy argues that “one option is immediate” while “the other is permanent.”

In 2007 the Joyce Foundation (which also supports editorial initiatives at WBEZ) gave $5 million in grants to the Nature Conservancy and three other groups to, in part, help build two-stage ditches in Indiana, Michigan and Ohio around the Wabash River watershed. And Kevin Willibey, a farmer who owns land near Ohio’s Fish Creek, built two-stage ditches on his property after seeing a pitch from Ward and his colleagues.

Willibey’s testimonial is included in a short film produced by the Nature Conservancy. Hear him explain why he feels good about the switch in the audio below:

Dynamic Range showcases hidden gems unearthed from Chicago Amplified’s vast archive of public events and appears on weekends. Andy Ward spoke at an event presented by the Peggy Notebart Nature Museum earlier this month. Click here to hear the event in its entirety.