If you don’t have money or insurance, you may have to wait for drug treatment

By By: Linda Paul

If you don’t have money or insurance, you may have to wait for drug treatment

By By: Linda Paul

People who know Caraline Scally well say that when sober, she’s curious, smart and generous. But when she’s strung out on heroin, Caraline says she’s a monster who cares only about herself – and her drugs. “I don’t care that you’re crying and telling me that you want me to be alive, and you don’t want me to die. I just don’t care,” she says.

As part of our Heroin, LLC series with the Chicago Reader, we’ve been tracking how heroin is moved from Mexico to Chicago, where it’s a big part of the economy on the city’s West Side. And we’ve been talking with people whose lives are affected by the drug trade, including people trying to recover from addiction. That’s how we got to talking with Caraline Scally.

Quiet childhood

Caraline grew up on a quiet cul de sac in west suburban Downer’s Grove. Very few cars came back there and the kids could play in the street. It was the kind of place you could cut through a neighbor’s yard to get somewhere, and nobody minded. She was a kid who loved reading and writing, and after school played park district soccer, which her father coached.

By middle school she still enjoyed many of her classes, but also got drunk a few times and was even grounded one entire summer for smoking pot.

The real trouble though, started in the summer after freshman year. She had just turned 16 when a new kid at the school asked if she and a friend would like to snort some heroin. It never occurred to her that she could become addicted.

“I just remember the euphoric feeling it gave me as soon as it went into my nose,” Caraline says. “I was absolutely in love with it.”

A new kind of high

Snorting graduated to shooting up and that summer she and her new acquaintance – she never really considered him a friend – started heading to the West Side of Chicago to buy heroin. She remembers the first time they drove there, this guy was giving her instructions, telling her they’d go to a certain street, get the dope quickly, and then she was to stash it “in her crotch” just in case they got pulled over by the police. The whole episode felt kind of exciting and risky.

Looking back at those trips now, as a 21-year old, she thinks back then she loved the ritual of it. “It was a high in itself, just the process of getting it,” Caraline says.

Her acquaintance was charging her $25 for a bag of heroin that cost him $10. She didn’t know she was getting ripped off, but did know she didn’t have that kind of cash. Caraline started stealing from her parents – and shoplifting clothing and jewelry from the “junior“ section of an upscale store.

She got caught though, and even before she had to step before a judge, her parents immediately whipped into action. “I mean my parents got me into an intensive outpatient program like within days of my arrest,” she says.

Caraline has a dual diagnosis for both addiction and depression. Since first entering treatment she’s experienced long stretches of sobriety, one time for 11 months, and a year and a half another time. But she’s also been in and out of both intensive outpatient and residential treatment – and the hospital a few times.

About nine months ago she was living in a halfway house, working full-time and doing well. But she got complacent, she tells me, and just left out of there one night to get high with a friend. He overdosed that night and she drove him to the hospital when other friends didn’t want to. The friend survived, but still — it was the worst night of her life. She realized she just couldn’t live like that anymore. So she checked herself into a residential program out in California that uses AA’s 12-step model and has group therapy, art therapy, exercise, journaling and Bible study.

Caraline plans to stay in California at least a year, away from all the temptations that Chicago presents. She feels she’s doing really well but says she has a lot of amends to make. “I’ve done a lot of damage to my family and I think they know – because I’ve been through it so much – that when I’m in the grip of that, it’s not me. And it’s not the person I want to be.”

She’s positive, she tells me, that if she goes back to heroin — she will die. So she’s working hard to make this treatment work. But all that treatment doesn’t come cheap.

The high cost of private treatment

“Where she is now is out of pocket for us about six thousand a month,” Joe Scally tells me. Joe is Caraline’s father. “The residential treatment she was in, was $700 a day.. .for six weeks,” Joe says. “Most of that was covered by insurance , but again, the insurance company said ‘we’ll cover it.’ Now we just found out in the last week, ‘oh wait a minute, we’re not going to cover 15 thousand of this.’ So we’re fighting that.”

Scally is a lawyer at the Child and Family Law Center in Highland Park. I’m sitting here with both him and fellow attorney, Micki Moran, who founded the practice. Moran also has a son who’s used heroin and tells me, “In our office everyone knows someone who died from a heroin overdose in their late teens, early twenties. And the parents find them in the morning, dead in the bed. And I wish there was a way to sugar-coat that, but there isn’t.”

Scally has pulled a picture of Caraline out of his wallet and I see a beautiful girl riding a horse, looking strong and healthy. This was taken shortly after she got to her program in California. “She looks really happy there,” Scally says, his voice getting thick with emotion. “And Micki will tell you. When they’re using, it’s almost like they’ve lost their souls. There’s nothing there.”

Out in the suburbs, I find out, people can have a skewed view of what’s causing the explosion of suburban kids using heroin. Moran takes pains to explain that this isn’t her view. But what she often hears from parents is that “the kid from Highland Park who drives down to the West Side and buys heroin, is the victim in some ways here.” She doesn’t agree with that, Moran says. But she hears people say that the “the drug dealer who’s standing on the corner selling it is the bad guy.”

I ask Moran who actually, really thinks that. “Almost everybody in the suburbs,” she says. “You know people have a completely different view of people who are dealing, as opposed to people who are buying.”

Suburban parents can be in denial about their own childrens’ culpability, both Scally and Moran tell me. They may think their kids are being lured by outside influences like rap music “which makes that whole drug-dealing culture seem glamorous and attractive. These are cocktail conversations,” Moran says.

But what about families without means?

Meanwhile, the prices Joe Scally and other parents are paying for private treatment get me wondering how people with a lower income could afford to access treatment for drug use.

To understand that, first I need a big picture view of the Chicago metro area’s heroin problem. So I head to the office of Kathie Kane-Willis, director of the Illinois Consortium on Drug Policy at Roosevelt University.

She’s sitting at her computer, crunching numbers for WBEZ so we can better understand who uses heroin, who gets treatment… and who dies.

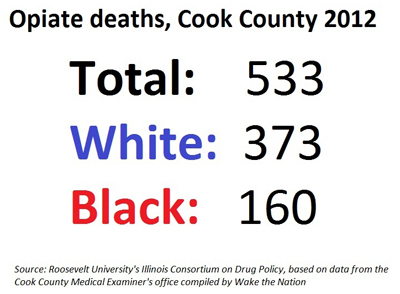

Turns out, in 2012 whites in Cook County were way more likely to die from opiates, which includes heroin, than African-Americans.

For people ages 31 to 35, for example, eight African Americans died from opiates. In that same age group, 72 whites died. For people ages 21 to 25, the same pattern held. Three deaths of African-Americans in Cook County in 2012 and 34 deaths of whites.

Kane-Willis says there’s no direct way to quantify the population of heroin users. So she looks at various measures, including hospital discharge data, emergency department mentions — and right this minute she’s on her computer checking admissions to government funded treatment in Illinois.

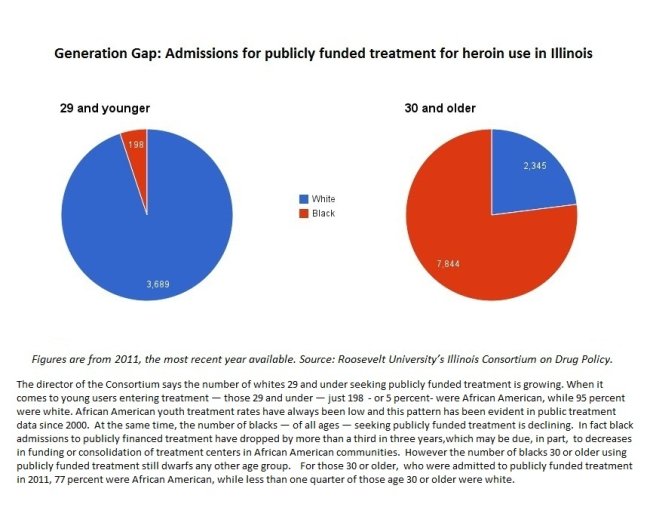

“When we look at African Americans versus whites entering treatment in 2011,” she says, “and we look at age breakdowns say under age 30 — we can see that only 198 African Americans entered treatment who were under age 30 in 2011, compared to 3,689 whites entering treatment. “

In fact, Kane-Willis says African American admissions to publicly financed treatment have dropped by more than a third in just three years. Searching for a cause, she speculates that some treatment centers may have closed or merged because of tardy payments from the state. And various government funding cuts could also be a factor.

But still, very few younger blacks enter treatment at all.

“I do think that there’s fewer young African-Americans who are using heroin,” Kane-Willis tells me. Other drugs, yes. But heroin, not so much.

About 20,000 people with substance abuse problems pass through the doors of Haymarket Center each year. Because many of these clients are poor, about three-quarters of them get their tabs picked up by the government. Sometimes it’s the children of those who were formerly well-to-do who end up at this center. Just about every treatment director I’ve talked to has a story about someone who’s had to refinance the mortgage of their home in order to pay for their child’s drug treatment.

“I’ve had patients here who have spent $200,000 on private treatment only to have relapsed,” Dr. Dan Lustig tells me. He’s head of clinical services at Haymarket. “And the parents become very frustrated. They get discouraged. But the reality is they don’t get the education that on average it takes six to seven different treatment attempts, different episodes of care before a person reaches any period of sustained recovery.“

Lustig says public treatment is typically every bit as effective as what you’ll find at private, for-profit centers. In fact several experts tell me that there’s often a higher standard at public treatment facilities, because they tend to use more evidence-based practices.

But there’s one big difference between private and publicly financed treatment, Lustig tells me. “What we have going on here is, and Haymarket Center is not unique to this, are waiting lists. For my outpatient program right now we’re looking at scheduling people this second week in January. “

And in the life of a heroin addict, can that be a big deal, I ask? “That can be the difference between life and death,” he says. “That is the key thing that our policymakers don’t get — is the importance of getting people access to treatment when that person needs it.”

It’s not hard to find someone who’s been on a waiting list for publicly financed treatment if you visit the Chicago Recovery Alliance’s needle exchange program. On the day after Thanksgiving I went to the van parked at the corner of Roosevelt and Whipple in the Lawndale neighborhood.

I’d only been there a few minutes when an amiable man in his mid-thirties walked in the door looking for some free supplies like needles, cookers, and an anti-overdose kit.

Lydell Harton was released from prison just a few weeks ago and he told me how he landed there. “My last three prison sentences have been a result of heroin,” he says. “My heroin addiction, me going out and trying to get money, going into stores and doing, you know, things out of character that I wouldn’t normally do to get money to support my habit.”

And what were his offenses? “Retail theft,” he says. “When it wasn’t retail theft it was trying to hustle the spots, to sell drugs to support my habit and so forth.”

Here’s the thing. Before committing two of the last three crimes that landed him in prison, Harton says he tried to enroll in publicly funded methadone treatment. But both times he was told that the waiting list was for about six months. And for a heroin addict, six months is an eternity.

“It could actually lead to death,” Harton says. “You know it takes money to support a drug habit, and as far as…in my situation I was looking for a change. I was trying to better myself to get off the heroin.”

But he didn’t get treatment fast enough and ended up in prison.

I tell Harton’s story to Roosevelt University’s Kathie Kane-Willis and ask if she thinks the negative impact of treatment waiting lists are overplayed. Her answer’s a little on the sarcastic side: “Well, if we don’t care about people contracting HIV, Hepatitis C — and possibly dying,” she says “then there’s really no problem with that.”

Besides her public health concerns, Kane-Willis has personal reasons to feel strongly about this. Earlier in her life, she was a heroin user living in California. She wanted to get on Methadone treatment but “there was a waiting list and I got arrested for shoplifting,” she tells me. While she was riding in the police car the police officer told her that there was no waiting list for treatment, that anybody could just walk in off the street and get Methadone treatment. But she knew better.

Lustig of Chicago’s Haymarket Center tells me there’s a correlation between drug addiction, arrests and imprisonment. Because when drug addicts are desperate for money, they will steal. “When you don’t have the beds available,” Lustig says, “this is the natural kind of path that people take. But we have to be aware that you’re not going to solve the drug problem in the State of Illinois —or anywhere else— by incarcerating these individuals.”

When you look at the enormous amount of funding spent on corrections and prisons, Lustig thinks that money would be better spent on expanding the slots in community-based organizations for people to get treatment on demand.

Some people think we are headed closer to treatment on demand. Come January, we’ll start seeing the impact of the Affordable Care Act, or Obamacare. Optimists in the field say once we’re past the glitches, people who sign up will have health insurance – or access to expanded Medicaid – and that should dramatically increase access to treatment for lower income people.

But Lustig sees a cloud over that. “This field is not ready for the Affordable Care Act,” he tells me. “It’s not ready because there’s not the volume of beds or slots needed so that when people need, or access treatment — it is available. “

The difference of opinion centers around whether treatment centers will be able to quickly ramp up and add capacity. Some treatment directors tell WBEZ there’ll be enough new clients to pay for expansion. Others say the reimbursement rates from government programs are so low, there’ll be no way to meet the new demand any time soon.

Patrick Smith contributed reporting for this story.