This year, for the first time ever, Americans’ preference for cremation will surpass their preference for burial, according to industry surveys conducted by the National Funeral Directors Association. That means that up until this point, most Americans expected to be buried. And they expected to stay that way. Forever. And they had the graves to prove it. The sheer number of cemeteries and their solid, long-lasting headstones, monuments and mausoleums testify to the strength of a cultural norm: most of us are destined for a final resting place.

But archaeologist David Keene says Chicago-area cemeteries — and the human remains within them — are less permanent than most of us think.

“We put expensive, well-crafted monuments on top of graves that last longer than any of us will,” he says. “So, cemeteries look like they’re there forever. But … they’re not.”

It didn’t take long for Chicago to move its dead around. Take early settler John Kinzie, for example. He was first buried in the cemetery behind Fort Dearborn, and had been dug up and reburied in two other cemeteries before landing in his final “final resting place” in Graceland Cemetery in the 1860s. Cemeteries are still prone to relocation, for much of the same reason they always were: Dead people are simply in the way of the living.

The idea of relocating the dead for the sake of modern demands and development doesn’t phase Oak Park native Samantha Kearney, who has a masters degree in urban planning. She’s well aware of Chicago’s history of cemetery relocation, but wanted to hear about the most notable examples. So, she sent Curious City this question:

There are thousands of bodies buried in Lincoln Park. How many people realize this and what other neighborhoods have similar histories?

Below, we list repurposed cemeteries and cemetery relocation projects that span from the city’s early days — when bodies were obstacles to more park space and a clean water supply — up until just a few years ago, when bodies were in the way of a new runway at O’Hare.

If you track these funerary shuffles, it’s easy to conclude that Keene’s right: Final resting places may not be so final. But you also conclude there’s a case to be made for better planning when it comes to moving the dead around. So, before we jump into our list, here’s something to think about from Melody Carvajal, who manages cemetery relocations for a living.

“This is not a textbook,” Carvajal says. “There has to be a way of doing it right. You have to sit and talk with the families for hours. … That’s okay. It’s okay to hear the emotion.”

Carvajal says she’s seen a number of cemetery relocation projects go awry, so she’s advocating for some industry standards. Among other recommendations: Relocation project planners should conduct genealogy, research the cemetery’s history, and, above all, reach out to surviving family members.

Carvajal says adopting such standards would allow everyone to evaluate the cemetery relocation process, for which there are currently no set standards. And if Carvajal is right about the increasing inevitability of relocating cemeteries that clash with the plans of modern developers, it’s necessary to ask: How do we plan for that?

With that, here’s a glimpse of some of Chicago’s repurposed or relocated cemeteries — the famous, the forgotten, and the tucked away.

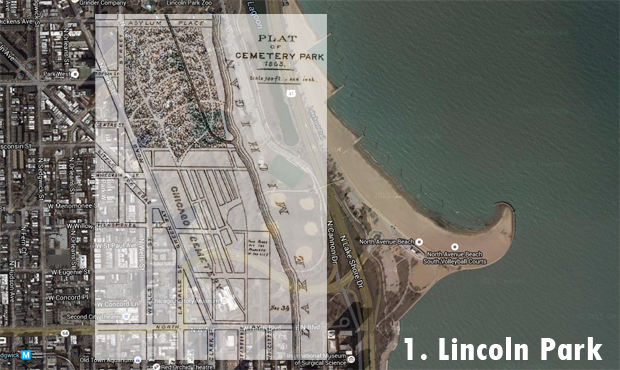

Lincoln Park

Formerly: Chicago City Cemetery

When: 1840s-1860s

Burials: 35,000

Remaining: 10,000 - 12,000

Lincoln Park is Chicago’s poster child of cemetery relocations. Burials in the City Cemetery, which spanned along the lakefront from North Avenue to Wisconsin Street., began in 1843, after the city relocated two smaller cemeteries on the northern and southern ends of town. The city owned the cemetery and it was run by the City Sexton, a public official who maintained the land and managed sales of burial plots.

By the mid-1850s, things were not going well. Chicago’s population (of both the living and the dead) had exploded, and there were accusations that the City Sexton had kind of let the City Cemetery go. Newspapers noted caskets emerging from the sandy ground, and the area reeked of death. Dr. John H. Rauch theorized that the “rising miasma” exuded by the deceased could become a city-wide health threat. Many people believed him.

Also, residents started to value green space more than burial space. Prominent Chicagoans routinely petitioned that the cemetery be either improved or removed; one consistent suggestion was to convert the cemetery into a park. The city finally agreed to close the cemetery in the early 1860s and planned to relocate graves to the newly-opened “rural” cemeteries of Rosehill, Graceland and Oak Woods.

That work was never fully completed. At its height, about 35,000 people were buried in the City Cemetery. Pamela Bannos, an artist and professor at Northwestern University who’s conducted extensive research on the cemetery in her project, Hidden Truths, estimates that between 10,000 and 12,000 bodies remained in the park by the time the last cemetery lot exchange costs were recorded in 1886.

The remaining dead included many of those buried in the city’s potter’s field, land reserved for the burial of the unknown and indigent. That area also contains thousands of other unidentified victims of cholera and the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

In 1869, the Lincoln Park Commissioners took on the job of creating the park and parade grounds the citizenry petitioned for. They ran into corpses as the work progressed and continued to do so for decades to come. To this day, construction in the park (say, for new parking lots) raises the prospect of unearthing the dead.

Dunning Square Shopping Center, housing development

Formerly: Cook County Infirmary, Cook County Insane Asylum

When: 1854-1911

Burials: 38,000

Another neighborhood that has a similar history to Lincoln Park is Dunning, on Chicago’s northwest side. In fact, some of the bodies disinterred from the potter’s field in Lincoln Park ended up here.

In the 1850s, the 320 acres of land between Irving Park Road and Montrose Avenue, and west to Oak Park Avenue was known as Dunning. It included the Cook County Infirmary, a “poor farm” and almshouse, and the Cook County Insane Asylum, both horrific places by all accounts. Many of the people who ended up at Dunning were poor and mentally ill, and often abused by the hospital staff.

See: The story of Dunning, a ‘tomb for the living’

There were at least three burial grounds at Dunning intended for poorhouse residents and asylum inmates, but also accessible by anyone in Cook Cook County whose family couldn’t afford to pay for traditional cemetery burial. It’s estimated that between 1854 and 1911, 38,000 people were buried there. Records of the dead’s identities and locations were poorly kept, and many were either lost or destroyed by the time the place closed in the 1970s.

The state sold off the property to developers. Over the years, it’s been common for construction projects to run into a corpse or two. In 1989, a backhoe operator accidentally split a corpse in half while doing work on a new housing project. The corpse appeared to be a red-headed Civil War soldier buried in his uniform, according to Chicago archaeologist David Keene, who was called to the scene.

A year later, when the construction of Wright College began on the grounds, Keene says he found human remains scattered just about everywhere. After a number of excavations, Keene pieced together the location of a 5-acre cemetery on the corner of Belle Plaine and Neenah Aves. Today, that’s Read-Dunning Memorial Park, the only vestige of the history of the original complex. The remaining area gave way to Dunning Square shopping center, which contains a Jewel store, the campus of Wright College, the Maryville Center for Children, along with housing and condominium developments.

In the spring of 2015, city workers were concerned that road construction in the Dunning area would uncover bodies, enough that the city postponed the work until ground-penetrating radar could locate them.

Oak Forest Health Center, Oak Forest Heritage Preserve

Formerly: Cook County Cemetery at Oak Forest

When: 1911-1971

Burials: 90,740

Today’s Oak Forest Health Center, located 22 miles southwest of Chicago, opened in 1910 as the Cook County Work Farm/Oak Forest Infirmary, a huge facility that, in addition to a hospital, contained a tuberculosis treatment center, a cottage colony, a fruit orchard, baseball grounds and … three cemeteries.

One of them, St. Gabriel Cemetery, was reserved for indigent Catholic patients of the hospital, and, today, contains no visible grave markers, aside from a dirt road that circles a statue of St. Francis of Assisi. The area is currently undeveloped and supervised by nearby St. Casimir Cemetery.

The other two cemeteries on the premises were owned by Cook County, and they served as burial grounds for the indigent, following the closure of the grounds at Dunning. Between 1911 to 1971, 90,740 people were buried there, estimates Barry Fleig, who runs a website dedicated to both Dunning and Oak Forest.

By 1923, the poor conditions of the County cemetery, located in the Northeast corner of the hospital grounds, were apparent. “This unsightly and barren area would be more in harmony with the rest of our Institutional premises if converted into a well kept and attractive park with the adornments of trees, shrubbery, flowers, and intersected with convenient walks and driveways,” wrote Anton J. Cermak in Cook County Infirmary’s annual report in 1923.

The county wouldn’t take the suggestion until 2012, when the Cook County Forest Preserve District unveiled plans to convert the area into a 176-acre park, complete with bike trails, a visitors center, and interpretive signage that would nod to the area’s history. However, those plans were temporarily halted after construction crews dug up hundreds of human bones while attempting to build the new trail system.

Today, those plans are still in the works. The bones were simply reburied. According to the Oak Forest Heritage Preserve Master Plan, the area of the “historic cemetery” will feature native grasses and prairie vegetation in a grid formation that vaguely alludes to the plats of bodies that lie beneath.

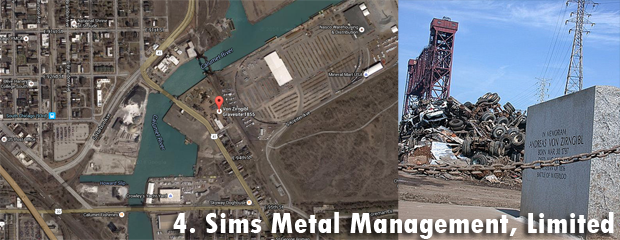

Sims Metal Management, Limited

Contains: The lone grave of Andreas von Zirngibl

When: 1850s (approx) - present

Burials: Definitely one, maybe more

The story of why there’s a single grave nestled in the middle of a South Side junkyard is a bit of a Chicago legend. Yes, there is a tombstone that marks the one-armed body of Andreas von Zirngibl, a Bavarian native who fought Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo. It’s located at 9331 S. Ewing Ave, right in the middle of a metal and electronics recycling site.

According to testimony from the von Zirngibl descendents in their 1895 Illinois Supreme Court case against the Calumet and Chicago Canal and Dock Co., which formerly owned the property, von Zirngibl bought 40 acres of land near the mouth of the Calumet River in 1854. He lived and fished there until he died of a fever in 1855.

The family says his last wish was to be buried on his homestead. As the story goes, they buried his body on the site, marked off the small platt with a white picket fence, and visited him from time to time.

By the late 1890s, the Canal and Dock company had purchased the land independently, seemingly without much fuss or notice from the Zirngibls (they had dropped the “von” by this time). But somehow or another, the family learned of the purchase, took the company to court, and told the judges that their deed to the land (now worth millions of dollars) was destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire.

Needless to say, the family couldn’t prove they owned the land, but they also couldn’t prove they didn’t own the land. As a compromise, the court ruled the Zirngibls could keep the area within the white picket fence surrounding the resting place of their family member, but the rest of the land rightfully belonged to the Canal and Dock company.

Today, the area is owned by Sims Metal Management Limited, and is a visible reminder of the human capacity to resist moving the dead at all costs, even in the face of development … and even if it doesn’t work out so well.

O’Hare Airport’s western runway

Formerly: St. Johannes Cemetery

When: 1837-2013

Burials: 1,200 (approx)

Remaining: 0

A high-profile cemetery relocation happened just a few years ago at O’Hare International Airport. The O’Hare modernization project included several new runways, one of which was platted right over a St. Johannes Cemetery.

Established in 1837, the small cemetery was located on the western edge of the airport. It spanned five acres and contained about 1,200 graves. It primarily served the congregation of a church that once stood on the grounds.

The relocation project took about five years to complete, and raised the ire of nearby residents and church congregations, who argued the cemetery shouldn’t be moved in the name of progress.

The runway was built anyway, and when it opened, the descendants of the relocated dead were invited to march down the runway to commemorate St. Johannes. No official memorial marks the landscape today.

An Oak Park native, Samantha Kearney says she’s committed to historic preservation, and that carries over as in interest in place through time. The idea of cemeteries as seemingly indestructible institutions fits the bill.

With a masters degree in urban planning and policy, Kearney rightly suspected that the Lincoln Park cemetery relocation wasn’t a one-time phenomena, and that there must’ve been other Chicago neighborhoods with similar histories.

Now that she’s taken in our findings and all this talk about cemetery relocation and moving bodies around, Kearney brings up a good reminder: A final resting place doesn’t have to be physical.

“Our final resting place is in the hearts and minds of the people we inspire,” she says.

Logan Jaffe is Curious City’s multimedia producer. Follow her on Twitter @loganjaffe.