Is American theater global or merely international?

By Jonathan Abarbanel

Is American theater global or merely international?

By Jonathan AbarbanelAmerican theater always has been international. Most of the classical standard repertory is made up of plays by Shakespeare, Schiller, Strindberg, Sophocles, Euripides, Moliere, Molnar, Chekhov, Ibsen, Pirandello, Calderon de la Barca, Brecht, Wilde, etc. You get the point.

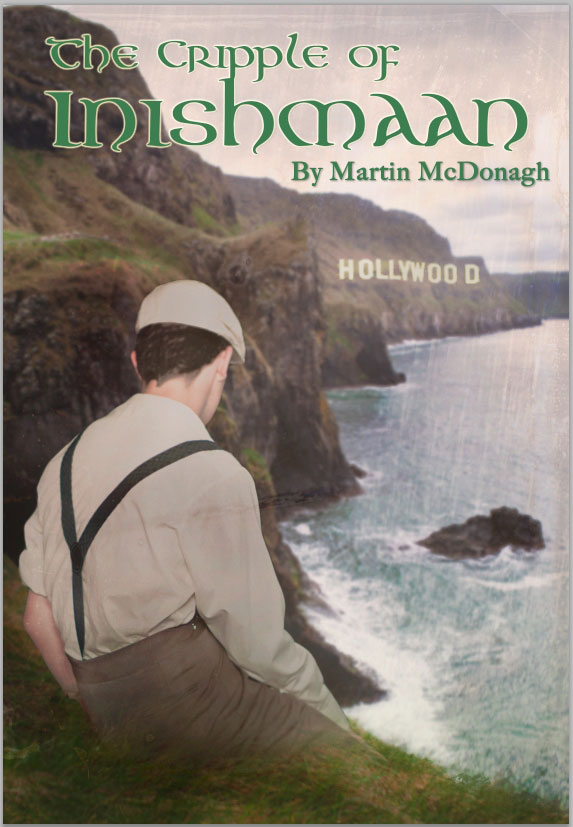

The standard repertory of contemporary plays also has an international flavor: Pinter, Beckett, Stoppard, Schaffer, Havel, Handke, Ayckbourn, Fugard, Reza, McDonagh, etc. Again, you get the point.

Still, the presence of foreign matter in Chicago theater is not the same as a repertory of work that truly spans the earth and girdles the globe. What so obviously is missing from the lists above is any representation of plays from beyond The Western World. Asia is missing, Africa is missing (except for Fugard, who is South African via European colonization), Central and South America are missing, Australia (English-speaking via European colonization) is missing. Our theater is international because it’s American-European, and not because it is truly global.

I recently returned from Warsaw, Poland where I was one of three United States delegates to the biennial World Congress of the International Association of Theatre Critics, a 56-year-old NGO organized under UNESCO statutes. While there I saw presentations on contemporary theater in China, Japan, Korea, India, Nigeria and Iran and other non-Western nations along with a healthy representation of European work. While we do occasionally see performances from non-Western or Third World nations on local stages, they almost always are in the form of brief visits by foreign troupes as part of a special presentation or festival. The admirable World’s Stage series at Chicago Shakespeare Theater comes to mind, as does my teenaged exposure to a touring Bunraku puppet theater from Japan.

As broadening as such viewings may be, they do not expand the range and repertory of American theater. For that, American artists and audiences need access to the world’s works in English. The challenge of bringing the work of such nations to indigenous American (and Chicago) theater companies must overcome the obvious barrier of language and the less-obvious barrier of familiarity.

But the less-obvious barrier of familiarity probably is even more difficult to overcome. Someone, or some group of individuals, must spend enough time seeing and hearing the theater of another culture and/or nation to develop at least a minimal depth of knowledge about it and to develop contacts within its artistic community. This aspect of familiarity might be summed up as knowledge and discrimination. It may require personal knowledge of a foreign language and/or various sub-dialects, and—perhaps more importantly—comfort with performance styles and traditions vastly different from American/Western norms.

As for more exotic parts of the world, our stages are barren for the most part. One of the few Chicago theater companies to present work by authors from Arabic, East Asian and South Asian cultures is Silk Road Rising; but even with Silk Road the emphasis is on the experiences of diaspora populations now living in America. The plays they offer by Korean-American or Indi-American or Egyptian-American authors are written in English. As important as their perspectives are, they are one step (or more) removed from contemporary theater in the nations of their heritage.

Short of major grants from private sources, or literary exchanges perhaps supported through cultural ministries (as does occasionally occur), or broader training (especially in languages) through institutions providing theater education, there’s no way to achieve true globalism in the work offered on local stages, especially when as it applies to non-Western cultures. We will have to make do with the guest troupes performing in their native languages (sometimes with projected English titles), or the odd translations and adaptations offered by a few dedicated theater companies.