Long lost civil rights speech helped inspire King’s dream

By Derek John

Long lost civil rights speech helped inspire King’s dream

By Derek John

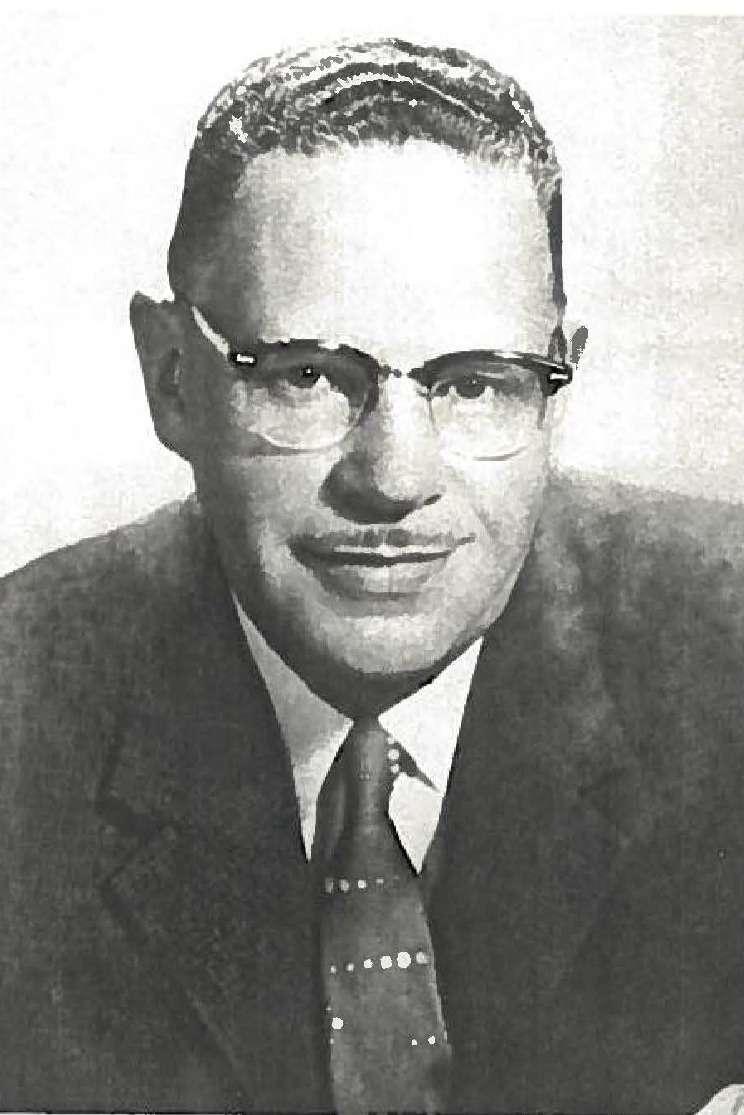

Carey died in 1981 and for many years, his speech was thought to be lost to history — its mere existence known only to a handful of scholars. But WBEZ recently discovered the landmark 1952 civil rights speech on a 16 rpm, 7-inch Gray Audograph disc at the Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kan.

Now for the first time in 60 years, we can listen again to Carey’s original speech — bold and brave for its time — including the famous crescendo at the end that directly inspired Dr. King.

Here’s the beginning of King’s final passage in his ‘I Have a Dream’ speech:

“This will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with a new meaning, ‘My country, ‘tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrim’s pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring.’ And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true. So let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire. Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York. Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania! Let freedom ring from the snowcapped Rockies of Colorado! Let freedom ring from the curvaceous peaks of California! But not only that; let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia! Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee! Let freedom ring from every hill and every molehill of Mississippi. From every mountainside, let freedom ring.”

Compare that to the earlier 1952 GOP convention speech by Archibald Carey:

“We, Negro Americans, sing with all loyal Americans: My country ‘tis of thee, Sweet land of liberty, Of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, Land of the Pilgrims’ pride From every mountainside Let freedom ring! That’s exactly what we mean – from every mountainside, let freedom ring. Not only from the Green Mountains and White Mountains of Vermont and New Hampshire; not only from the Catskills of New York; but from the Ozarks in Arkansas, from the Stone Mountain in Georgia, from the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. Let it ring not only for the minorities of the United States, but for the disinherited of all the earth! May the Republican Party, under God, from every mountainside, LET FREEDOM RING!”

Why the 1952 Republican national convention?

Carey was one of the few GOP office holders in Chicago, black or white, when the 1952 convention came to town and he was already known for his public speaking. While it may seem odd in hindsight that Carey gave the speech at a GOP convention, Vanderbilt University historian and Carey biographer Dennis C. Dickerson reminds us that the times were very different then.

“When push came to shove it was usually GOP votes that could be counted on for black civil rights,” he says. “Carey knew that and was trying to help the party re-brand itself as the party of Lincoln.”

Dickerson continued, “When he uses that poetry and prose he’s speaking to more than just the GOP party. He’s speaking to the nation at large that queries ‘what do these black people want?’”

Carey’s speech was widely commended and he received hundreds of telegrams from all over the country, including some promoting him to be Dwight D. Eisenhower’s running mate. After the Eisenhower-Nixon ticket was elected Carey was appointed to several administration posts and became a delegate to the United Nations. When Barry Goldwater became the party’s nominee in 1964, however, Carey made the decision to switch over to the Democrats.

How did Carey’s words end up in MLK Jr’s ‘I Have a Dream’ speech?

Although Carey delivered his address a full three years before the Montgomery bus boycott, it was only a matter of time before he and Dr. King crossed paths. Eventually the Georgia preacher found his way to Carey’s church in Chicago.

The historic Quinn Chapel AME still stands on South Wabash Avenue today and on a recent Sunday morning, some longtime members recalled Dr. King’s visits fondly.

I remember two occasions that he was at Quinn Chapel,” says Carolyn Dodd. “I think the first one it was such a crowd here I was sitting in the balcony and I don’t think I had to sit in the balcony but once or twice since that time.” Ruth Dunham remembers when Dr. King came to Chicago to fight for open housing on the West Side. “Rev. Carey was with him then,” she recalled. “They marched together, and you got a feeling they were very close, very close.”

Close enough to share their speeches? Dennis C. Dickerson says we’ll probably never know.

“We don’t have a letter saying ‘Dear Martin, here’s my speech. Good luck using it in your speech.’ But clearly we know they interacted many times and corresponded many times,” he said.

This isn’t the first time questions have been raised about Dr. King’s source material (the most glaring example being his early doctoral dissertation). But Dickerson says in this case you have to understand the black church’s oral traditions.

“Let me put it like this. if one of my students did it [plagiarize], we’d have a real problem,” Dickerson said. “But it is the custom among black clergy to hear a great sermon or a great speech and just say to the author I’m using that. “

Dorothy E. Patton, Carey’s niece, still remembers watching her uncle’s convention speech on television in 1952. Patton says both Carey and Dr. King drew from the same rhetorical well of scripture and history — her uncle simply got there first.

“I’m a scientist and if you look at the history of science,” Patton says, “somebody did the first experiment and it sort of got in the back of the file cabinet somewhere, and then somebody else comes along and runs with it.”

It’s a nice thought: the elder Carey passing the baton to the younger King who carried it across the finish line in 1963. And why not? Dickerson, in his biography, includes a letter from Carey with the following words.

“When I need help,” Carey wrote, “I can count on Martin Luther King, and when he needs help he can count on me.”

Special thanks to archivist Kathy Struss at the Eisenhower Presidential Library and WBEZ engineer Adam Yoffe.

Derek L. John is WBEZ’s Community Bureaus Editor. Follow him at @DerekLJohn.