Museum helps build better science teachers

By Linda Lutton

Museum helps build better science teachers

By Linda LuttonIn a science classroom across from the coal mine exhibit at the Museum of Science and Industry, the students are sitting at high lab tables, studying Petri dishes full of bacteria.

At the front of the room, the teacher explains the lesson’s objectives—compare animal and bacterial cells, review pathological and non-pathological bacteria. But there is a broader goal here, one the Museum of Science and Industry wants to help achieve: improve science teaching in Chicago and its suburbs.

The students here are all teachers, all responsible for imparting science to upper-elementary or middle-school students. It’s a job that many in this class—and many teachers in many grammar schools—feel decidedly unprepared for.

“Definitely, that’s why I’m here,” says Chicago Public Schools teacher Joel Spears. “I teach 5th grade, and it’s self-contained, so I teach all the subjects—math, science, language arts, social science. I went in not knowing how to teach science, really. I didn’t have the materials or the know-how to even teach it properly.”

Once a month. Spears and dozens other teachers enrolled in this professional development course come to the museum for a day of lessons, curricula, and materials they can then take back to their classrooms across the Chicago metro region. Since the teacher training courses were first offered in 2006, 804 teachers from 320 schools have participated. About two-thirds of teachers are from Chicago public schools.

Many of the teachers say they’re trying to tap into the natural enthusiasm kids have for science—when it’s taught right.

“We did some previous lessons that I learned here, and they love it. They always want to do science,” says Spears. “’Cause it’s hands on—they’re not just reading. They’re constructing, they’re doing.”

On a recent morning, the Museum of Science and Industry instructor runs a lesson exactly as if she’s teaching middle schoolers. The teachers put themselves in their students’ shoes. They work activities, make Venn diagrams, and then get to the fun part: an experiment with black light and Glo Germ that exposed bacteria still present on their hands, even after washing.

Near the back of the class, teacher Jonathan Fisher looks at a cell diagram before him and admits this is the first time he has seen flagella since high school. The philosophy major avoided the life sciences in college. Now—ironically, he says—he’s teaching the subject to fourth graders. He says he can implement certain techniques and lessons almost as soon as he learns them. Others, like a genetics lesson his students loved, take more planning.

“We had an experiment where the students used Styrofoam blocks and different body parts—so limbs and dowel rods and different-sized eyes,” says Fisher, who teaches at Murphy Elementary on the Northwest Side. “That was a hands-on way for them to understand how genetics are passed down from one generation to the next. And the classroom couldn’t have been more excited, flipping the coins to figure out which genes would be passed on to their kids. (The lesson) took something very abstract like genes and genetics and turned it into something the students could relate to.”

Fisher is one of eight teachers from Murphy who’ve been involved in the museum’s teacher courses. He said his school is serious about becoming better at teaching science, but he also says it’s not hard to figure out what the priorities are in education right now. “If it’s not reading or math, then it’s not an emphasis. Learning to be a teacher, all the other subjects could be cool, but if it’s not reading or math, that won’t be a focus.”

The role of museums in science education

There’s been a big push lately to improve the teaching of science in American schools, with more focus on STEM education— Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics. Andrea Ingram, the Museum of Science and Industry’s vice president of education and guest services, says museums can play a role in that.

“One of the challenges in the U.S. in getting kids engaged in science is that we don’t have enough really high-quality science teachers in the middle grades—and that’s kind of like the early childhood of science,” says Ingram. “We either capture kids’ enthusiasm there, get them committed to science—or we don’t.”

Ingram says museums across the nation are important partners in improving science instruction, especially given tight school budgets. They are popular with philanthropic, business and civic leaders. They can fill specific needs that may vary community by community. And where else can you find tornados, lightning, and real cow eyeballs to dissect?

Programs like the teacher training courses at the Museum of Science and Industry build important bridges between schools and museums, says Nathan Richie, who chairs the education committee of the American Alliance of Museums: “Museums can use the resources at their disposal—be it the location that they have, the content, the artifacts, the experts—and help train the practitioners in the classroom to use those to engage students.”

Richie says the role museums are playing in science education has increased with a new national emphasis on STEM education. Ironically, in an age of shrinking budgets and more dictates over how much time students must be in the classroom, Richie says schools take fewer field trips. This is a way of getting the museum into schools.

Marbles and mechanical energy

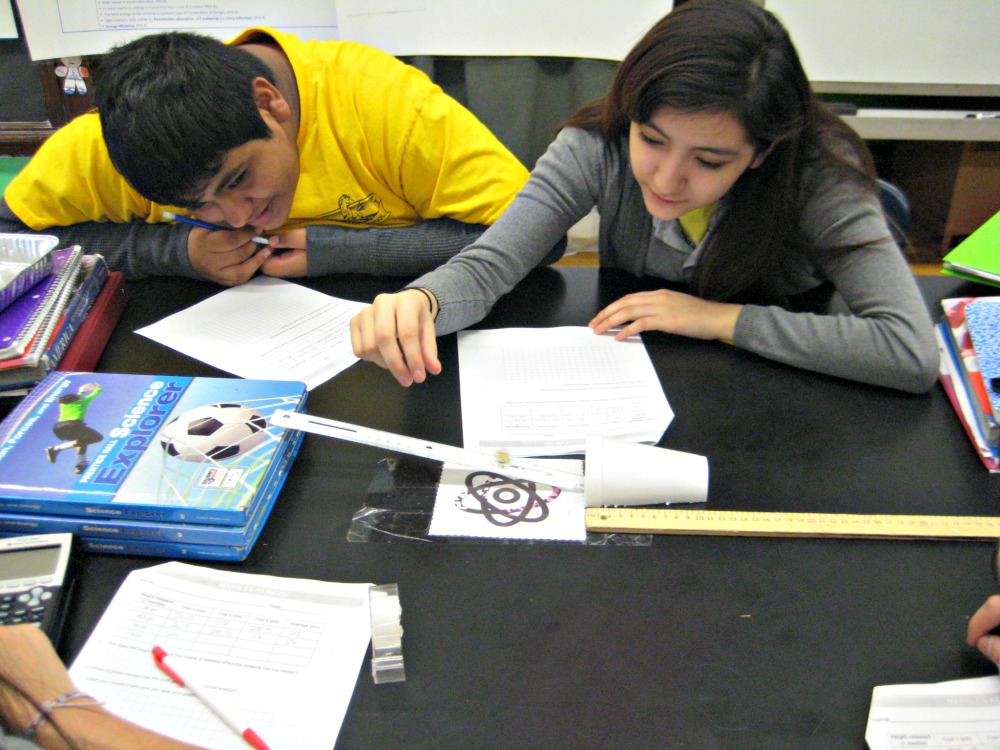

In Graciela Olmos’ eighth grade classroom at Sawyer Elementary on Chicago’s Southwest Side, kids are rolling marbles down incline planes, measuring how far the marbles push a little Styrofoam cup. Olmos first saw this lesson about mechanical energy at the museum.

Olmos says she’s used to being told to teach to higher standards. The museum has shown her how.

“They model for us. This is how it’s going to look. And that’s something we lack.”

Though she won’t say that’s the only thing she lacks. “We need so many things,” Olmos says. “We need to have science labs with gas lines and sinks. If my specialty is science, then let it be science. Don’t give me so many other things to do aside of that.”

Science education professor Joanne Olson says getting dedicated, well-trained science teahcers has been “a perpetual challenge for us in science education, particularly at the elementary grades.”

Olson, who is also president of the Association for Science Teacher Education, says she’s been advocating for years for schools to have science specialists.

“It’s like the PE teacher,” says Olson. “You have one teacher who’s dedicated to that particular subject area, and that way the teacher can be very well prepared in that area and doesn’t have to take on literacy instruction, math, in these other areas.”

Olson says research shows that 65 percent of elementary teachers have gotten fewer than six total hours of science training in the last three years. “And we know that teachers need about 100 hours,” she says. “So we’re far under. Anything that can be done to help is a good thing.”

A study of the Museum of Science and Industry’s teacher training program is being released today by well-known science curriculum expert William Schmidt, of the Education Policy Center at Michigan State University.

It finds the teachers trained by the museum know more science—and, significantly, so do their students.

The Museum is marking the news of its success with an announcement—it’s committing to train 1,000 middle-grade teachers in science over the next five years.