My interview with Jorge Luis Borges

By Achy Obejas

My interview with Jorge Luis Borges

By Achy Obejas

The assignment should have never been mine — I was just a kid — but he was Hispanic and I was Hispanic and I think somebody very concerned about the growing Hispanic population must have trumped book editor Henry Kisor’s good sense.

In any case, Kisor suggested only one question — about the ongoing Falklands War — and sent me off. Titled, “Jorge Luis Borges: A blind literary artist who paints with memory” the article ran on Sunday, May 9, 1982.

Jorge Luis Borges is a relic.

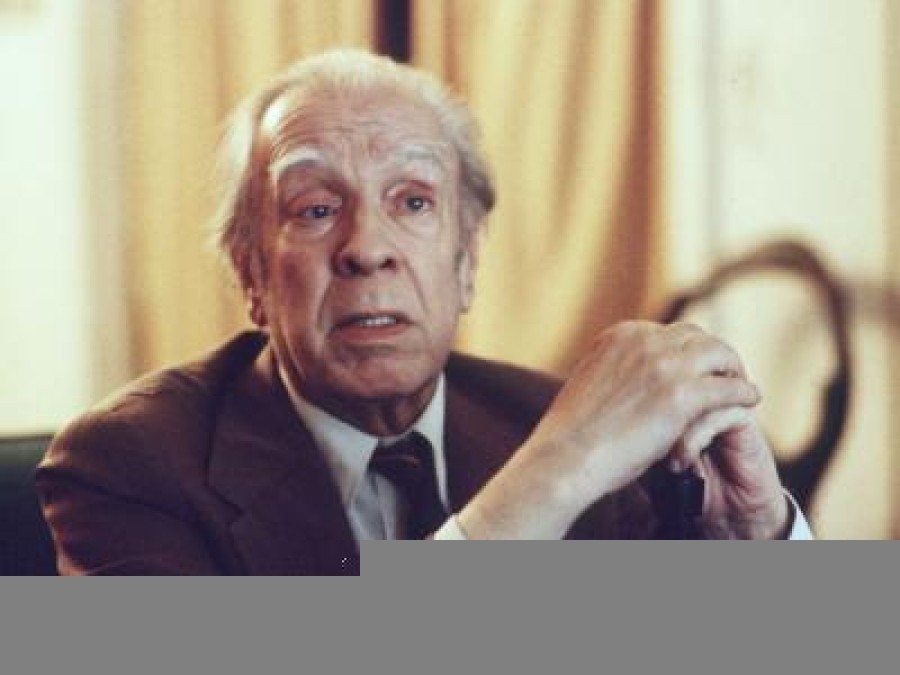

Although he has hardly a wrinkle on his face, Borges’ features have little definition. They seem to melt from his face. His mouth in particular appears to be making an effort to stay horizontal. Each corner drops mutely unless Borges pulls it up while speaking.

Small, frail, and much like a boy when excited, the Argentine peppers his conversation with anecdotes about an old romantic reality.

He can talk about his home town of Buenos Aires and give the story of almost everry neighborhood. What he relates, however, is not history.

As he tells his stories, the names of both real and imaginary characters mingle: Bioy-Casares, Muraña and Paredes, his friends from the past; the famous cuchilleros, or knife-wielders of the Argentine pampas, who were bloody assassins with a brutal code of chivalry; the legendary tango singer, Gardel; Don Segundo Sombra, a character created from a real man by the writer Guiraldes — the list goes on.

“Of course, all memories are weak,” Borges said during a recent conversation at the University of Chicago. A conference on his early works, “Borges: Beginnings,” was held there last month. A frequently mentioned candidate for the Nobel Prize in literature, Borges is often mentioned in the same sentence with Kafka, Proust and Joyce.

“Memory changes things. Every time we remember something, after the first time, we’re not remembering the event, but the first memory of the event. Then the experience of the second memory and so on.”

Blind since 1955 as a consequence of a hereditary disease that turned his world into a murky yellow, Borges must rely on memory to chronicle much of his life of the last 30 years. But memory is an old obsession for Borges. It goes hand in hand with time, with reality vs. imagination. A short story, “El Memorioso,” is about a boy cursed with a perfect memory, a memory that does allow him to forget anything.

In “El Memorioso,” Borges may have been writing, in a fantastic way of course, about himself. When someone mentioned Bloomington, Ind., for example, he recalled a visit from five years before at Indiana University for a conference. And then he listed every restaurant in the city at which he ate.

“There is a vegetarian restaurant there called The Tao,” he said, amused. “”I do my best to be a vegetarian. I’m sick and tired of meat. In Argentina, they give you meat three times a day. I can’t stand it.”

He remembers dreams, engravings and illustrations in the encyclopedias in his father’s library in Buenos Aires.

“What we remember is slightly askew,” he said, almost apologetic. “My dates are very dim. I can remember any amount of verses, tales, stanzas, many languages, but nothing of my own life in terms of dates.”

Because of his blindness, 82 year-old Borges depends now on memory for the literature that is so dear to him. Conversation is the only time that he can really savor it, so he punctuates his thoughts by reciting verses. Kipling and Whitman are his favorites. He pronounces their words and breathes ellipses after each poem.

“I can’t read, I can’t write — my letters overlap — so I just try to plan things for the future, things for tales, poems, fables, metaphors and so on. What else can I do?” he asked. “Of course, I’m lonely a lot. When I’m in Buenos Aires, I never go to cocktail parties, to commencements, the Academy of Letters — I never go there.”

He goes on lecture tours because he does not want to be alone.

“I can’t see,” said Bores. “But I can feel. I can feel the people and the places.”

***

Borges has friends (“very kind, very forgiving friends”) but they’re all much younger than he. Most of his peers, most of the people who could share in his memories instead of just receiving them, are dead. It accents his loneliness.

“I talk to my sister, whom I love very much,” he said. He also owns a large white cat he describes as having golden eyes. But the description is someone else’s, because Borges has never seen her. When he tells it, though, his eyes, aimless and gray, widen with wonder.

“I’m very fond of words,” he explained. In conversation, he likes to stop and explain each one, as if they have individual personalities, incalculable value.

“Do you know where the word moon originates?” Borges asked. The question is typical. It could be any word. “The original Saxon word was moona. It was masculine and not very pretty. But moon is a beautiful word.”

An expert on Old English, Borges is also a noted Anglophile. However, at a reception before the conference, a professor approached Borges on the question of the Argentine take-over of the Falkland Islands. Borges responded very deliberately: “I couldn’t care less.”

Later, his personal secretary asked that the issue not be addressed. The reason? Even though Borges is virtually untouchable, even by the Argentine generals, they can make life very difficult for him. For example, they can restrict his travels.

When he was kidded about how he must be torn between the two countries, he just smiled and took off on another subject.

“Dim is a beautiful word. Uncanny is a very beautiful word too,” said Borges. “In Spanish, sombra is very beautiful, don’t you think so?”

Words for Borges are all very beautiful, like small treasures. Words in English draw his attention more than Spanish, because they’re shorter and more economical. His own English, spoken with both a Hispanic and British accent, is efficient and marked by one-syllable words.

“Reading poetry, when you’re greatly moved, that endears the words and they stick,” he said. “You only remember things that you really care for.”

For more about Borges, click here.