On Chicago’s West Side, school teaches character. Math, too.

By Robin Amer

On Chicago’s West Side, school teaches character. Math, too.

By Robin Amer

In education, sometimes it’s the oldest questions that matter most: What makes a good teacher? How does a school get test scores up? But, these days, educators are also asking this question: How important are all the things tests can’t measure?

A middle school on Chicago’s West Side thinks it has an answer. We take you to Chicago Jesuit Academy, a school that teaches — and grades — life skills right up there with book learning.

Eighth grader Brandyn Snow and his mom have this morning routine: As he makes his way to school, he has to call and let her know he’s safe — four different times.

“I’m headed towards Lake now,” he tells her, as the 85 bus passes underneath the Green Line. “I’ll call you at Jackson, then when I get on bus, then when I get to school.”

“At first I thought she didn’t trust me,” he says. “But she’s just trying to protect me.”

“What is she protecting you from?” I ask him.

“Well, danger,” he replies. “People trying to hurt other people.”

Like that group of older boys who beat him up in elementary school.

Or those guys who shot and killed those two teenagers waiting for the bus back in October.

People like that.

Brandyn calls his mom a fourth time as the bus lets him off at the corner of Laramie and Jackson, at Chicago Jesuit Academy. Ninety-six 5th through 8th graders go to school here — all boys, mostly from rough West Side neighborhoods like Brandyn’s.

Teaching character in a morning handshake

When Brandyn walks into CJA’s spare but sunny atrium every morning, he sees Dave Diehl, the Dean of Students, standing by the door, holding a clip board.

Brandyn knows the rules: First, take off your jacket. Then, look Mr. Diehl in the eye and shake his hand.

“Good morning Mr. Diehl.”

“Good morning Mr. Snow,” Diehl answers, checking off Brandyn’s name. “Do you have your belt on?”

“Yes.”

“You may head up.”

These rules are an explicit part of the school’s culture. But they’re also triage — a check for any problems the kids might be having.

“Do the students often forget their belts?” I ask Diehl. “I noticed you asking each of them if they have it on.”

“They forget it occasionally,” he tells me. “It’s more of a check for them — it’s an indicator. If they’ve forgotten that they’re forgetting other things.”

Discipline and dress codes aren’t new in education. But here, there’s an additional question: Can you teach middle school kids practical life skills and character — along with math?

High expectations

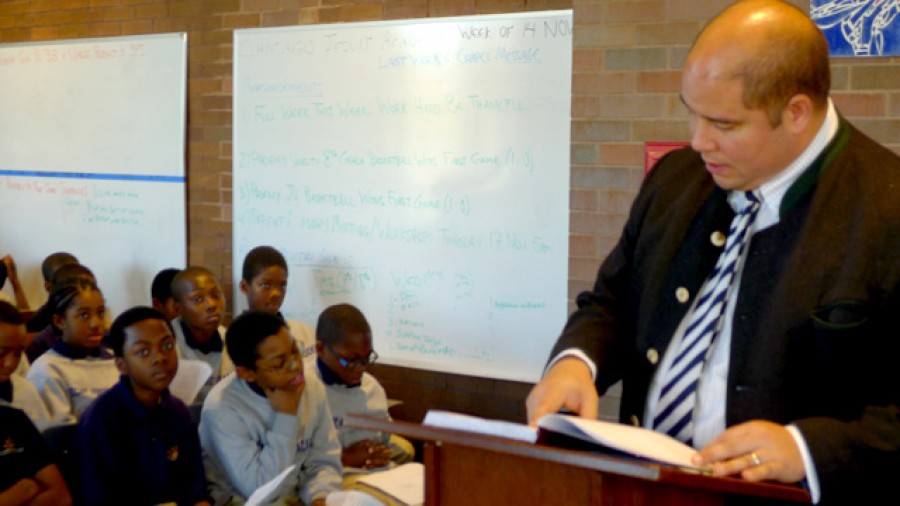

![Dave Diehl, CJA’s Dean of Students, also teaches 8th grade algebra. Here, Diehl helps Brandyn Snow [left] and his classmates in the advanced group through a math exercise. (WBEZ/Robin Amer)](https://s3.amazonaws.com/wbez-cdn/legacy/image/math%20class%20edit.jpg)

CJA is expensive: $17,500 per student per year. But kids go here basically for free—most of the tuition is paid by private donors, and the school only takes kids whose families don’t make a lot of money.

Most of the students went to poorly performing elementary schools before they applied to this 7-year-old school, which is part of a loose national network of faith-based schools called NativityMiguel.

CJA administrators insist they don’t “cream the crop” during admissions by taking only boys with good test scores — they say they’ve admitted students who perform as low as the 10th percentile nationally.

But they do look at other things: Parental involvement, for instance, and behaviors that suggest how a boy might cope in a demanding environment. That’s because students are expected to leave here testing above grade level. Last year’s 8th graders tested, on average, at the 11th grade level.

The goal is for them to get into top high schools, with scholarships. Then, for them to compete at those schools, to thrive — alongside more privileged classmates.

Lessons learned

Tom Beckley is the principal at CJA. He’s a former Navy man, who sometimes greets his students like new recruits— with a handshake and a hearty “welcome aboard.”

In his cluttered office, tucked in a corner of the main atrium, Beckley says the school didn’t always emphasize character and behavior the way it does now.

At first, they mainly pushed students academically, trying to make up for time lost in failing elementary schools. That approach seemed to work: Many of their first graduates had strong test scores and got into good high schools – Loyola, St. Ignatius, even East Coast boarding schools.

But then, Beckley says, they did not do well in 9th grade.

“They went to high school and struggled right out of the gate,” he says. “We scratched our heads and said, but look at their test scores! We realized, boy, that’s only a small part of the equation.”

CJA stays in touch with all of their graduates, and these days those first grads have settled into their college prep high schools and are doing pretty well. But as freshly minted 9th graders they had bad study habits and made bad choices: Their homework folders were a mess; they always chose gym over study hall. And, they had attitude problems: Beckley says these kids couldn’t control their impulses, and no one could tell them what to do. He says pushing them academically hadn’t been enough.

Beckley says he realized that when you look at grades, it doesn’t say attitude, organization and math. It just says math. So about a year and a half ago the school put in place a new grading policy, one that took attitude and organization more seriously.

Now at CJA, it’s not enough to master Y=X. Now, 70 percent of every grade a student gets here– on every spelling worksheet, every book report - is based on behavior and habits that CJA calls executive function.

Beckley rattles off some of the expectations involved: “You are doing every single problem of a mathematics assignment regardless of whether or not you have gotten each one wrong. You know how to put down objectives in your notebook and you always have a heading on your paper. You’re always contacting your teacher outside of class at least once in a week.”

“Those are the most important skills they need,” he says. “What we see over and over, is that students with average academic aptitude can really be successful if they have an excellent set of executive function skills.”

So if student is failing at CJA, that doesn’t mean they don’t get the math. They just might not have their act together.

“It’s possible here – theoretically,” Beckley says, “for a student to never get a single math problem or spelling word or vocabulary word correct and still pass with a 70 percent if they have tried their hardest and done every single piece on their rubrics for executive function.”

“But what we know as educators,” he says, “is that while that’s theoretically possible, the student who’s doing all those things — who’s engaged, paying attention, who’s asking for help, who’s talking to their teachers outside the classroom, who’s turning things in on time - that guy learns.”

Not everyone was convinced, at first. Beckley says that when they adopted this new grading policy, even the school’s own teachers were skeptical — “really worried,” he says, about what would happen. Some parents were skeptical, too. Like Brandyn’s mom, Tina Jackson.

“I was like, oh, this is not going be good, because this is too much for a young child,” she says. “Why go through all this? You gotta make sure you have your belt on, your shoes are tied, they have to be a certain color.”

And it was too much for some kids. In the past year and a half, 12 students have been asked to leave the school because of academic or behavior problems. And 8 were withdrawn by their parents, who thought the school was too demanding or who disagreed with their approach.

Experts weigh in

In the classroom that doubles as a lunch room 7th grade math and social studies teacher Matte Durkin rings the lunch bell with three crisp strokes of the gong. The room falls silent as he calls their attention to the white board, where the school has written up the day’s menu.

“Please take three meat balls,” he says. “Make sure you grab some cauliflower and fruit. Get all those on your plates. Please take one piece of bread. And make sure to drink your milk.” At his signal, the students take their seats.

Education researchers don’t argue that behavior and good study habits, like the kind CJA emphasizes, are important. But they say it isn’t clear yet what tactics are best for teaching the kind of behaviors and attitudes that lead to student success.

These points are among the conclusions in a survey the University of Chicago’s Consortium on Chicago School Research will release next month. The study looks at the existing research on non-cognitive assessment –all the stuff tests don’t measure.

They haven’t looked at CJA specifically, because they don’t study private schools. But a lot of schools are trying to teach this stuff. That includes a New York school that gives students separate report cards that measure character. And schools that emphasize what researchers call academic tenacity, or grit: If I fail …do I try again?

But Beckley is convinced CJA’s focusing on the right stuff to help kids transition to high school. He says they have to treat kids — as young as 9 — like grownups, now. It’s why they’re called “Mr. Snow” instead of “Brandyn,” and why they’re held to such high standards.

“One thing I think is very, very unfair,” he says, is “if you’re growing up on the West Side of Chicago, and you want to be able to access a first rate private high school, by end of your 7th grade year that’s a done deal. I know I wasn’t ready for that in 7th grade, and yet, they have to be.”

He says that since they’ve started using their new policies CJA’s teachers have come around. And Brandyn’s mom says the structure has helped her son get his act together.

“I honestly don’t think Brandyn would be in 8th grade,” if it weren’t for the school’s rigor, she says. “I think I’d be dealing with a child that didn’t want to go to school.”

Support: The other side of the equation

One thing researchers say we do know is that especially for middle school kids, two things are critical: clear expectations and a lot of support.

Beckley teaches Formation, a class to help eighth graders deal with the pressure of their young, complicated lives.

“So yesterday I asked for some honesty,” he says, addressing the class from the front of the room.

“I’d argue that all of you have fear or stress about what? Raise your hand if you remember.”

The answer is high school choices. Chicago area high schools send out their acceptance letters starting this week, and the topic is on every 8th grader’s mind.

So this week he’s asked them to think about the very best and very worst things that have ever happened to them — to establish a scale. He wants them to think in this way: If that thing I went through before was worse than this stress now, then I can get through this stress ok.

They’ve started with essays on the worst thing that’s ever happened to them.

“No one has anything to be ashamed of,” Beckley reassures them, and calls the first student to the front of the room.

Some of today’s “worst experience“ stories have happy endings: One boy describes how scared he was the time he accidentally lost track of his 4-year-old brother on the CTA, even though the brother turned up okay.

But other stories belie traumatic experiences: One student describes the day his uncle was killed — stabbed in the neck. Another explains that his mom’s boyfriend is serving a life sentence in prison for murder, after a fight with an upstairs neighbor escalated.

After each essay, Beckley asks the class to evaluate it, according to a three-point scale he’s handed out before class.

“Guys, honesty?” Beckley asks.

The boys cry out in unison: “Three!”

“Is there an exceptionally strong sense of audience and voice?”

“Three!”

Then Beckley calls Brandyn’s cousin Davion up to the front of the room.

He faces the class and begins to read: “When I was four months old my dad got shot and so he’s paralyzed.”

As he continues, his voice begins to waver. “It really pisses me off to know that the man who shot my dad is still walking around somewhere in the world. The man who took that away from me I want to kill him when I get older.”

He begins to cry. “But I don’t want to because I don’t want to go to jail.”

“Davion, you can have a seat,” Beckley tells the boy.

Davion does sit down, but he’s still crying. Brandyn goes over to comfort him.

Then Beckley gets up and stands in front of the class. His head is bent; his lips are pursed— like he’s struggling to figure out what to say.

“I’m proud of you guys…every day,” he says, finally. “Let’s get to work. Go ahead and pack your things.”

Davion is still crying when he walks into the hallway, but adults walk with him to see the school’s social worker. I’m not allowed to follow him into her office, but I see him later that day, and he seems to be okay.

High school persistence

Ten hours after he said good-bye to his mom this morning Brandyn sits behind his drum set for jazz band practice. Today they’re rehearsing the jazz standard “Mood Indigo.”

Brandyn would really like to go to one of Chicago’s arts high schools. He’s auditioned for two. He’s also taken the entrance exams for Loyola and for selective enrollment public schools like Whitney Young. His mom, Tina Jackson, says his motivation makes her proud.

“In the beginning he just wanted to graduate,” she says. “Now he wants to go to college and knows which one and how much it costs.”

But she says she also knows how hard it will be for Brandyn to be on that path – and how hard it will be for him to stay there.