Small is big at new nanotechnology lab in Wheeling

By Linda Lutton

Small is big at new nanotechnology lab in Wheeling

By Linda LuttonU.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan helped inaugurate a special science lab in the Chicago area Thursday—and attended a separate event promoting more rigorous learning standards.

Wheeling High School officials say their nanotechnology lab is the first of its kind in a U.S. public high school.

Teacher Nancy Heintz says the lab’s high-powered microscopes can drill down to the nano level. How small is that? Think of the Lincoln Memorial on the back side of a penny, she says.

“If you imagined the eyelash on the Lincoln in the Lincoln Memorial on the back of the penny— that gets you pretty close to the nano level.”

Heintz says teachers were able to see single atoms of copper when they came to learn how to use the scanning electron microscopes and atomic force microscopes over the summer.

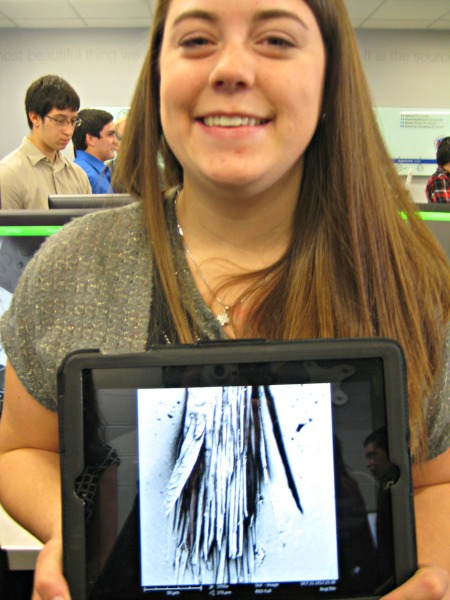

On Thursday, students showed off images of things they’d seen close up: butterfly wings, strands of hair, a DVD.

Senior Bryan Zaremba was impressed by paper. “It looks almost like a spider web, you can see all the fibers,” he said.

“This is zoomed in at 3,300 times, so it’s pretty small,” explained his lab partner, Eric Kaplan. On the computer screen was an image that looked more like a gray, post-apocalyptic forest than a scrap from someone’s notebook.

Next to Zaremba was a scanning electron microscope –which looks like a large desktop computer tower. “There’s a crystal in here that shoots electrons down at a sample, and when the electrons hit the sample, they bounce back to detectors, and they build an image,” Zaremba says.

The lab is part of the school’s focus on STEM education—short for science, technology , engineering, and mathematics. It cost $615,000—$400,000 for equipment and $215,000 for upgrades to the lab itself. The district received a $250,000 grant from the state.

Duncan has joined a national push for more STEM education, which is being fueled in part by American students’ lackluster performance on international science and math exams.

Duncan says two million high paying jobs are unfilled right now, many in the STEM fields.

“Honestly, it’s not even just about the jobs,” Duncan said at Wheeling. “It’s about having students being excited about coming to school every single day. It’s about having real relevance to the real world.”

The lab isn’t just for honors students—Wheeling’s goal is to get every student to use it. “Some of these kids might go on to be technicians, where they could get a living wage job right when they get out of high school,” says Heintz. Others will go on to study engineering, biology, or chemistry at high levels.

Wheeling students are already working with the entomology lab at the University of Illinois. They’re examining silk produced by silkworms in Madagascar, and comparing it to silk made by domesticated silk worms.

Many colleges don’t have the sort of technology Wheeling High does.

“I’m planning on studying nanotechnology in college. This class really drove me to choose that for my career,” says senior Stephanie Maglaris, who plans to combine nanotechnology with civil or mechanical engineering. “It’s really interesting—and it’s gonna open up a whole new field of jobs and studies,” says Maglaris.

Duncan touted Wheeling as a school that had set high standards for students. The school has seen a big demographic shift in the past decade. Half of students are Latino, around 40 percent are low-income.

At a separate townhall event sponsored by the University of Chicago’s Institute of Politics, Duncan highlighted another priority of the administration, the Common Core learning standards.

The standards have been adopted by a total of 45 states—including Illinois, Indiana and Wisconsin, and are debuting in many schools this fall.

“Raising standards is one of the most important things we can do to help all kids, but especially disadvantaged children, have a chance to be successful,” Duncan told reporters at the event. “The hard part is the implementation, how we support teachers and principals and students themselves and families in the hard work of hitting this higher bar.”

During a townhall style forum, Duncan was challenged by audience members about where the arts and critical thinking fit in the standards.

Many in the audience applauded when economist and education expert Fred Hess suggested it’s a mistake to introduce high-stakes teacher evaluations at the same time states are rolling out new standards and tests.