Uptown’s moment as a ‘Hillbilly Heaven’

By Jesse Dukes

Uptown’s moment as a ‘Hillbilly Heaven’

By Jesse DukesHillbilly Heaven. That was a common nickname for Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood in the 1950s and 1960s. For about twenty years, the neighborhood, which sits between Lakeview and Rogers Park, was locally famous for being home to thousands of white Southern migrants, many of whom came from the Appalachian region. And while many migrants lived in other neighborhoods on the North Side, Uptown had the greatest concentration of Southerners and, not coincidentally, it was where the poorest members of that community lived.

The Southern influence stuck around through the ‘70s, but by the ‘90s, it was difficult to find many Southerners in Uptown. The history fascinated questioner Matthew Byrd, a college student originally from Chicago. Byrd is descended from Southern migrants (both of his mother’s parents were born in West Virginia), and he grew up visiting his extended family in the South and asking his grandparents about Uptown in the “Hillbilly Heaven” days.

“I always asked them why they came to Uptown … and they never gave me a definitive answer. I wanted to know why they all came to that neighborhood. … Like, why didn’t they come to like Bridgeport or Humboldt Park. Why was it Uptown?”

His question for Curious City:

Why did so many migrants from Appalachia end up in Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood during the ’50s and ’60s? Why did so many leave?

With help from Byrd’s own family, historians and others, we’re able to provide a quick account of how the neighborhood transformed from a swank, Midwestern urban neighborhood to one where, according to sociologist Todd Gitlin: “You’d walk down the street [and] you’d hear some country western song coming down the window, and as you proceeded down the street, you’d hear the same song coming out of other windows. You heard a lot of Southern accents. You saw a lot of Southern license plates.”

The Great (White) Migration

It doesn’t take a great mental leap to grasp why so many white Southerners came to Chicago when they did. Like most migrant groups, they came because there were abundant jobs. While we might be more familiar with “The Second Great Migration” (1940 - 1970) of African Americans from the South, to the North, Midwest, and West, more white migrants than black made the trek to the North after World War II.

Chad Berry, a historian at Berea College, takes up the phenomenon in Southern Migrants, Northern Exiles: “Anyone familiar with the history of especially the Upland South will immediately ask not so much why southerners left their region in droves in the twentieth century, but why it took them so long to pack their bags. …” The Upland South, a region that includes most of Appalachia as well as places farther west such as Western Kentucky and Arkansas, had been in an economic slump since before the Civil War, and it offered few economies apart from subsistence farming and coal mining.

But before 1920, Southerners hoping to leave had few choices. Large Northern industries could largely satisfy their hunger for cheap labor by recruiting immigrants from other countries. Chicago’s Polish, Irish, Italian, and many other European populations all have their roots in the late 19th century. But in the 1920s, the U.S., still reeling from World War I, clamped down on immigration with a series of federal laws that drastically restricted the immigrant labor pool. This meant big industry had to turn inward for cheap labor. Berry says “They look in three places: whites, blacks, and domestic-born Latino people.”

Above: A 1967 pamphlet for The Chicago Southern Center, an organization that helped Southern migrants adjust to urban living. (Courtesy Chicago History Museum)

Southern whites and blacks began to come north, but just as the migration started, the Great Depression slowed down industry so much that jobs became scarce. The migration was put on hold until 1941. “And then during and after World War II, there’s an amazing demand for manufacturing,” says Berry. “Chicago was a real magnet for workers, just as Detroit, Indianapolis and Cleveland and other countless places were in the Midwest.”

In the late 1940s (a bit earlier than Matthew Byrd had ventured), white Southerners began travelling north again, lured by stories of abundant jobs. Roger Guy, a sociologist who interviewed Southerners in Uptown during the 1990s says “Migrants spoke about being able to leave a job, and being able to walk across the street and get another one.”

Southerners worked in light industrial factories such as Polaroid and Zenith. Some performed more brutal and less lucrative day labor in the steel mills. Others found work in carpentry, or in the city’s prominent candy industry, or even as handymen or shade tree mechanics.

The jobs brought changes to the traditional order of Southern life. First off, women often performed the same work that men did. And, the Southerners now worked in the same workplaces as African Americans, Latinos, and recent European immigrants. Southern migrants who hailed from the more isolated Appalachian region had never even met Catholics or Jews before coming North.

Uptown: A neighborhood ready for migrants

The new arrivals needed a place to arrive within the city — a neighborhood that was near industrial work but also offered affordable rents. They found Uptown. While we don’t know which Southern migrant first settled there, or precisely when that happened, a series of events primed Uptown as a suitable port of entry.

According to Roger Guy, Uptown in the 1920s rivaled The Loop as the premier shopping and entertainment destination in Chicago. It was the heart of Chicago’s silent film industry, and there were several monolithic brick residential hotels where professionals could stay for weeks, months or longer, depending on their busy and shifting schedules.Young single people could live in fancy Art-Deco apartments and enjoy an active nightlife. The Uptown Theater — at the time, Chicago’s second-largest entertainment venue — showed movies and stage shows, and contained a nightclub and several shops. The “Moorish”-looking Aragon theater featured highbrow jazz music, while the Green Mill Gardens and the Arcadia Ballroom catered to younger, wilder patrons.

The depressed economy of the 1930s saw the neighborhood change significantly. The film industry went to Hollywood, the nightlife became seedier and many of the wealthier tenants left. To save money, landlords deferred maintenance, and to keep their units profitable, they began subdividing large luxury apartments into single- and double-room units to rent to a less wealthy clientele. Many residential hotel rooms were similarly converted to small studios. By the 1950s, Uptown was full of cheap, formerly fancy apartments.

‘Hillbilly Heaven’

As a port of entry, many Southerners came to Uptown because they knew somebody there, and knew they could find cheap rent. Those who could find good jobs often moved to other, quieter neighborhoods, but those who couldn’t tended to stay in Uptown. That meant it became the locus of Southern white poverty in Chicago.

Many Southerners who lived there remember the neighborhood fondly. They enjoyed the opportunity to hear country music, or even familiar accents. But our questioner’s grandmother, Linda Lambert, says her family was in for a shock when they arrived from West Virginia in 1965.

“There were many Southern people,” she says, “but they weren’t the Southern people we were used to being around. They were a little rough around the edges. If I was getting ready to go to the store, my dad would watch me walk down the block. Somebody would be whistling at me, and it was kind of upsetting.”

Above: Photos of Appalachian migrants in Uptown taken by Bob Rehak, who documented the neighborhood throughout the 1970s. See his photo book: Chicago’s Uptown: 1973-77 for more.

Southerners developed a bad reputation among some Chicagoans. In the 1950s, The Chicago Tribune ran a series of articles about Southerners in Uptown, featuring reporter Norma Lee Browning. Although she developed a reputation as a tough investigative reporter, Browning’s articles were loaded with stereotypes about rural Southerners. Here’s an excerpt from the series’ first article, entitled “Girl Reporter Visits Jungles of Hillbillies”:

“Authorities are reluctant to point a finger at any one segment of the population or nationality group, but they agree that the southern hillbilly migrants, who have descended on Chicago like a plague of locusts in the last few years, have the lowest standard of living and moral code [if any] of all, the biggest capacity for liquor, and the most savage and vicious tactics when drunk, which is most of the time.”

Another article purported to document the newcomers’ family life: “They get married one day, unmarried the next, and in the confusion of common law marriages many children never know who their parents are — and nobody cares.”

Despite the apparent gross exaggerations and fabrications from the Chicago Tribune’s reporting, it appears there were some unsavory characters in Uptown. Roger Guy explains Uptown had some of the characteristics of an oil boomtown, where young single men would work for a few weeks, and then use their wages to party.

Migrant Linda Lambert says, “I think it’s like any other culture, you got your good and you got your bad. There was a lot of poverty. That is true. But a lot of people who lived there lived there until they could do better. It was just a stop in the road.”

Displacement

If some Uptown Southerners represented a rougher element, others just struggled to survive in a city that was not always hospitable. Virginia Bowers, a former resident who originally came from West Virginia, says that tenants in Uptown often had to deal with unscrupulous landlords. She had worked managing property. During interviews with Roger Guy she’d said: “I lost my first job as a manager in a building because I stuck up for a couple that had been bitten by a rat. The owner wanted me to lie about it. I told [the housing inspector] that I couldn’t lie to him. I was a mother myself and I couldn’t lie.”

There were numerous reports of landlords cutting corners to save money. According to tenants and local activists, owners turned off the heat, electricity, or water in buildings. They deferred maintenance to save money, and harassed or evicted tenants who complained. Activists including scholar Todd Gitlin and Helen Shiller (who became the area’s alderman in 1987) organized tenants to resist unsanitary conditions through rent strikes, public protest and other tactics. In some cases, they were able to bring about better housing conditions.

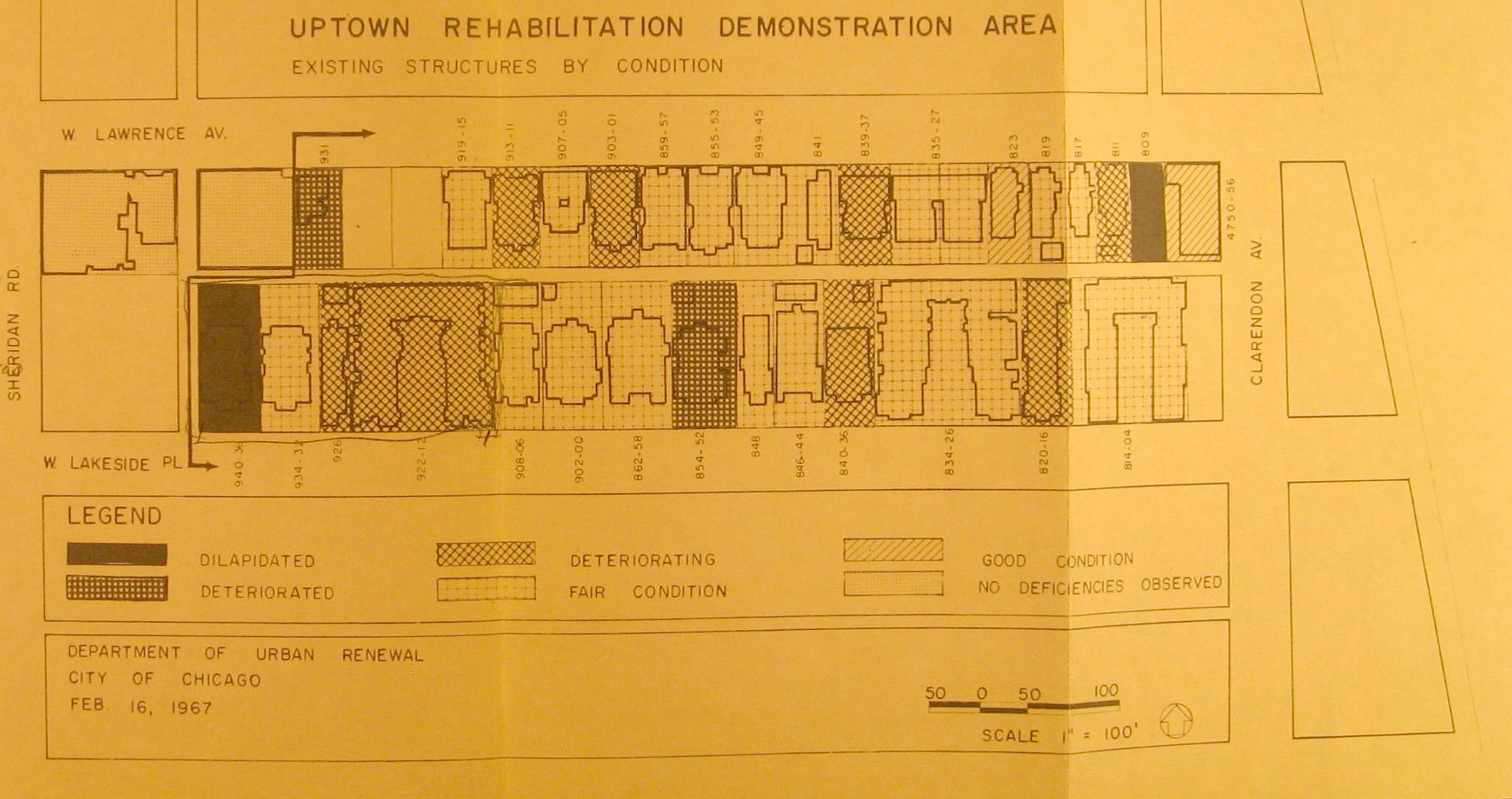

But even as Southerners in Uptown sought to improve housing conditions for the poor in Uptown, the city and developers had other plans. By the late 1960s, abundant jobs were scarce, and Uptown’s reputation as a rough place with substandard housing grew worse. The city instituted a series of public works projects, including razing several square blocks to relocate Harry S. Truman City College. A group called the “Uptown Area People’s Planning Organization” organized under the leadership of Chuck Geary. Geary was a migrant himself — a Korean War veteran, erstwhile hitchhiker, father of eight and a preacher. He worked with architect Rodney Wright to develop an alternative to the Truman College plan called Hank Williams Village, named after the famous country singer. According to Roger Guy, the village would be a “planned community with subsidized apartments, a pharmacy, and an employment agency.” It was never built.

After the Truman College relocation effort won out, the area saw a series of developments. The city and developers argued urban renewal was necessary to replace substandard housing and rid Uptown of blight. Helen Shiller argues the poor in Uptown, who also included Native Americans, Japanese-American migrants, Latinos, and a handful of other groups, were seen as undesirable by the city and business community. “The city’s policy, in the North Side at least, was to create public works projects in specific communities where they wanted to remove people,” she says.

Shiller argues that planning for Uptown could have been more inclusive, preserving housing for the poor, including white Southerners. But, she says, that didn’t happen.

“A handful of developers were redefining the community in real estate terms and claiming parts of it,” she says. “They had deep pockets and built up large tracts of family housing, kicked people out wholesale, rehabbed the buildings, and tripled and even quadrupled the rent.”

Whether or not the city and developers actively targeted poor white Southerners for removal, the evictions and rising rents seem to have driven thousands, if not tens of thousands out of Uptown, and likely out of Chicago. The way demographic data was collected makes it difficult to say, but Roger Guy feels that by the 1990s there were few signs left that Uptown had ever housed tens of thousands of Southerners. He says in 1994 and 1995, he volunteered to register voters.

“I walked along those streets in the heart of Uptown and went in buildings knocking on doors,” he says. “I don’t remember encountering a Southerner.”

Into the fabric of Chicago

According to historian Chad Berry, many Southerners left Uptown on their own terms before urban renewal and gentrification ever took place. He says academics and journalists found they could document the once-high concentration of Southerners in Uptown, but it proved more difficult to document the lives of those who were successful and left the neighborhood.

Matthew Byrd’s grandparents, Glen and Linda Lambert, are among the Southerners who did well for themselves. Glen landed a job at S&C Electric on his first full day in Chicago in 1969 and the couple lived north of Uptown, in Rogers Park. He worked at the company forty-three years and that stable, well-paying job (along with supplemental work from Linda) allowed them to move to a shady street in nearby Ravenswood in 1978, raise kids, and eventually retire to Kentucky.

Byrd is proud his home city provided opportunity and a better life to his grandparents and other Southerners, as it has for migrants and immigrants from countless places. But he thinks it’s important to remember the full history, and believes the Chicago let down the thousands of white Southerners who were pushed out of Uptown by eviction and rising rents.

“There’s success and there’s failure,” Byrd says. “I think the failure means the next time a large group of people from another part of the country or world that’s kind of maligned comes here, just do better by them than we did people from Appalachia or people Poland, Africa, Vietnam. Do better by them.”

Matthew Byrd has always been close to his grandparents, Glen and Linda Lambert. He grew up visiting extended family in West Virginia whenever possible, and pumping both of his grandparents for stories of what it was like coming to Chicago. He’s a student at the University of Iowa, and already working as a journalist in Iowa City.

Byrd is well aware that he’s probably in the last generation of his family to hear his grandparents’ stories of childhoods in West Virginia, or Chicago’s “Hillbilly Heaven” of the 1960s.

“My kids aren’t going to have the same access to memories I had,” he says. “There’s no physical remnants. … There’s very few. The story is going to die soon, and I just wish more people could know about it.”

Jesse Dukes is Curious City’s audio producer. He doesn’t tweet, but follow @loganjaffe (Curious City’s multimedia producer) for occasional #IfJesseTweeted tweets.

Further reading on the topic of Appalachian migrants to Uptown:

Gitlin, Todd, and Nanci Hollander. Uptown; Poor Whites in Chicago. New York: Harper & Row, 1970.

Berry, Chad. Southern Migrants, Northern Exiles. Urbana: U of Illinois, 2000.