Versailles ‘73: When black models took to a French runway and changed the fashion world

By Alison Cuddy

Versailles ‘73: When black models took to a French runway and changed the fashion world

By Alison Cuddy

If your fashion sense is tingling big time, no surprise: For weeks now clotheshorses around the world have been racing from one major spring fashion show to another in Milan, Paris, New York, London and now back again to Paris, this time for 2014 ready to wear.

Of course back in the day, Paris wouldn’t have been caught dead doing anything other than haute couture.

But today, in an era when the designer Karl Lagerfeld accuses mass retailer H&M of “snobbery,” the debates over the merits of fashion “made by hand in the atelier” versus clothing “fresh out of the factory and onto the rack” are not only long over, they’re irrelevant.

Still, if you’re itching for a glimpse of one of fashion’s seminal skirmishes, be sure to check out Versailles ‘73: American Runway Revolution.

The film, which open this Friday at Facets Cinémathèque, documents a famous Franco-American fashion show that took place at the Chateau du Versailles in 1973.

On the surface the event was simple: five established and newer designers from each country would parade their wares.

But as more people – and the press – got involved, what was first conceived as a fundraiser to restore the by then crumbling digs of the Sun King, quickly became a new Franco-American contretemps. Only this time, the battle lines were drawn in silhouettes and stilettos.

The main divide, according to Deborah Riley Draper’s film, was: Who owns fashion?

The French, with their couture standards, refined aesthetics, and pantheon of god-like (Christian Dior) creators?

Or the Americans, with their brash sportswear, street style and upstart designers like Stephen Burrows? (By the way, Draper credits Burrows – and not that other designer – with introducing the wrap dress to Americans.)

Each side relied on an arsenal of weapons. They brought heavy-hitting designers: Dior, Pierre Cardin, Emanuel Ungaro, Hubert de Givenchy and Yves St. Laurent for the French; Anne Klein, Oscar de la Renta, Bill Blass, Halston and Burrows for the Americans.

Both sides also relied on some extra sizzle.

The French brought out an aging but mesmerizing Josephine Baker, wearing a skin-tight sequin-blazoned catsuit. The Americans retaliated with Liza Minnelli, fresh off her Oscar win for Cabaret and sporting mile-long eyelashes.

The French then responded with a line of dancers from Crazy Horse, the Parisian erotic revue, who it’s made clear would let nothing get between them and their luxurious furs.

But the Americans’ real secret weapon, as well as the absolute stars of the show? 12 African-American models, including Pat Cleveland, Norma Jean Darden, Alva Chinn and Charlene Dash.

At that point, black models were still a relatively rare sight on international runways (and at American fashion houses). And as one of the film’s talking heads says, these women were “so fierce, so strong. They’d never seen anything like that.”

So the women stole the show, and of course the Americans “won,” pulling off a 35-minute show that seemed positively breathtaking compared to the 2 1/2-hour spectacle produced by the French.

They also made a statement, not just about fashion, but about race.

As Metropolitan Museum of Art Costume Institute Curator Harold Korda puts it, “When you have a black woman sashaying and then throwing her train, it becomes something that is different than the more polite expression of standard fashion runway style of that period.”

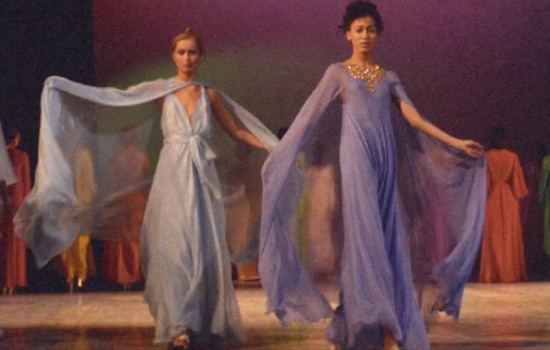

It’s impossible not to agree, watching these women strut in Burrow’s gorgeous pop-art colored gowns and Halston’s slinky creations, and then voguing (yes, even in 1973) to disco beats. These are the women, who along with Beverly Johnson or the great Donyale Luna, paved the way and set an attitude for black supermodels like Naomi Campbell and Tyra Banks.

But even at the time, these women were not total unknowns. By 1970 Charlene Dash had been in Vogue and was considered one of the top black models in the U.S. Alva Chinn was a model for Halston. Many of them had walked runways throughout the U.S. thanks to the Ebony Fashion Fair, which Eunice Johnson launched in the late 1950s to introduce black Americans to high fashion.

And as foreign as they may have been to the French, they were also outsiders at home. In 1970 Pat Cleveland moved to Paris for a time, away from what she considered America’s “racist attitudes” toward black models.

There is so much more I want to know about these women, whose personalities are so lively and looks so undiminished (proving that once a model, always a model). How did they make their way into the exclusionary world of fashion? What kind of relationships did they establish with black designers (like Stephen Burrows) and taste makers like Eunice Johnson of Ebony?

The film, focused as it is on the backstory and aftermath of the Versailles show, doesn’t really delve into these questions or the women’s deeper biography. And without that (some of which can be gleaned in Draper’s recent interview with Tavis Smiley) there are times when the film runs the risk of fetishizing them.

One after another talking head swoons over the models “freshness” and “different way of moving,” as if they were exotic creatures from another planet. They were new and different, and they, along with these designers, made American fashion look and feel very new and different.

That these models possessed such power, even from a marginalized position and if only for a brief but exhilarating moment, is truly worth telling. And timely. The tales of how Americans and Europeans alike struggle to really represent diversity in fashion are as perennial as the spring shows.

But to me that point kind of gets swamped by the overarching and more familiar story of American sartorial and cultural achievement, and the film’s emphasis on the triumph of American power over French tradition.

Of course that’s Draper’s point precisely: This very American story is equally the story of these models. But to make their achievement less of a footnote and more of a force within the history of fashion would require much more time and attention than Versailles ‘73: American Runway Revolution can offer.

It would likely take a whole other documentary. And you know, we may just get that. Deborah Riley Draper is apparently trying to develop a documentary about the late African-American model Donyale Luna.

Versailles ‘73: American Runway Revolution is at Facets Cinémathèque February 22-28.