Why Jefferson Street isn’t in the Loop

By John R. Schmidt

Why Jefferson Street isn’t in the Loop

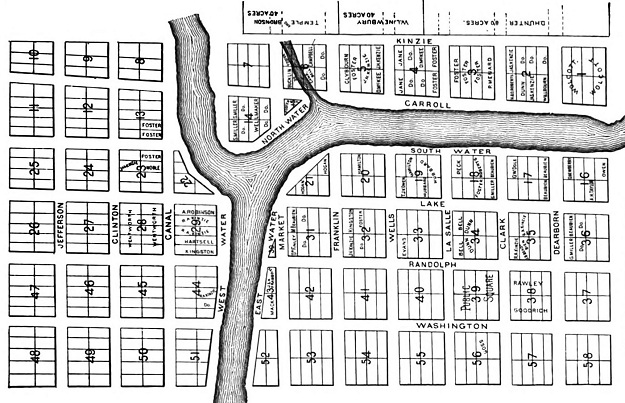

By John R. SchmidtAs a Chicago historian, I’ve fielded all sorts of questions. Believe it or not, one of the most often asked questions has been—Why is Jefferson Street off by itself, instead of with the rest of the downtown president streets?

Thomas Jefferson was one of our greatest presidents. He wrote the Declaration of Independence. His face is on nickels, and on Mount Rushmore, and on the $2 bill. He has his own memorial in Washington. Our city certainly could have remembered him with a more prominent street.

I came up with various answers why Jefferson was so neglected. Truth is, I didn’t really know for sure until recently. Then I got my own copy of A.T. Andreas’s History of Chicago.

Andreas published his opus in the 1880s, and it’s unbelievable—three volumes, running a total of 2,000 pages of tiny type. It has just about anything you’d want to know about early Chicago, and even more things that you’d never image you wanted to know.

(One example of the latter—For Chicago’s first mayoral election in 1837, Andreas doesn’t just present the totals. Rather, he goes down the entire list of 709 registered voters by name, and tells us how each person voted! Secret ballots weren’t yet in fashion in 1837.)

I’d worked with the Andreas books before, but always in a library. Now all the volumes had been digitalized and I could afford to purchase them, and page through at my leisure. I finally found the answer to the Jefferson Street question in Volume One, on page 194.