Chicago’s flammable ‘fire escapes’

By Maura Connors, Jonathan Katz, Lee Kuhn, Hannah Loftus, Jennifer Brandel

Chicago’s flammable ‘fire escapes’

By Maura Connors, Jonathan Katz, Lee Kuhn, Hannah Loftus, Jennifer Brandel

Editor’s note: The podcast episode above is one of two audio stories related to this topic. A shorter, excerpted version is paired with our story on the history of a structure that frequently has wooden porches: the Chicago two-flat.

If the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 taught the city one thing, it’s that wood does not stand up to flames. This fact did not escape notice of Manhattanite-turned-Chicagoan Lee Kuhn, who moved to the Hyde Park neighborhood to attend the University of Chicago. He settled into a three-flat building which — like untold numbers of similar buildings across the city — had a wooden back porch.

At first glance, Lee said, the wooden structure’s use as a fire escape seemed illogical: “If this is a fire escape and it’s made out of wood — what’s going on here?”

So Lee turned to Curious City with this question:

What is the origin of Chicago’s distinctive wooden fire escapes? Are they actually effective during fires?

As part of a special collaboration with a University of Chicago course called “Buildings as Evidence,” Lee and fellow classmates Jonathan Katz, Maura Connors, and Hannah Loftus helped Curious City find answers. Along the way, we learned how economics sometimes overrules logic, and there’s a bit of irony here, too: While not technically “fire escapes,” these wooden porches are meant to keep residents safer from fire.

For more than a century, Chicago’s building code has demanded two means of egress (i.e., multiple exits) on typical two- and three-flat buildings, a fact that City of Chicago regulation and code reviewer Bob Fahlstrom confirmed after looking through the city’s code library. He said as early as 1906 (the farthest back he could view), the building code stated that every two or three-flat apartment (also called “tenements” at that time) required either a fire escape or two separate stairs: one staircase located at the front of the building and another at the back.

Building code regulations were still new in the early 1900s, but Chicago did have the Great Chicago Fire under its belt as well as the Iroquois Theater fire. And as the now ubiquitous short apartment buildings and homes that carpet most Chicago neighborhoods were being built in the late 1800s and into the 1900s, the two-exit requirement seemed a regulation born out of hard experience.

Fahlstrom said the rationale was common sense. “In a fire situation,” he said, “if you’ve got one exit and the fire gets between you and that exit, you’re in real danger.”

While technically not a fire escape, back porches did satisfy building code requirements and make for another option if a front exit was unpassable, and vice versa.

Party in the front, business in the back

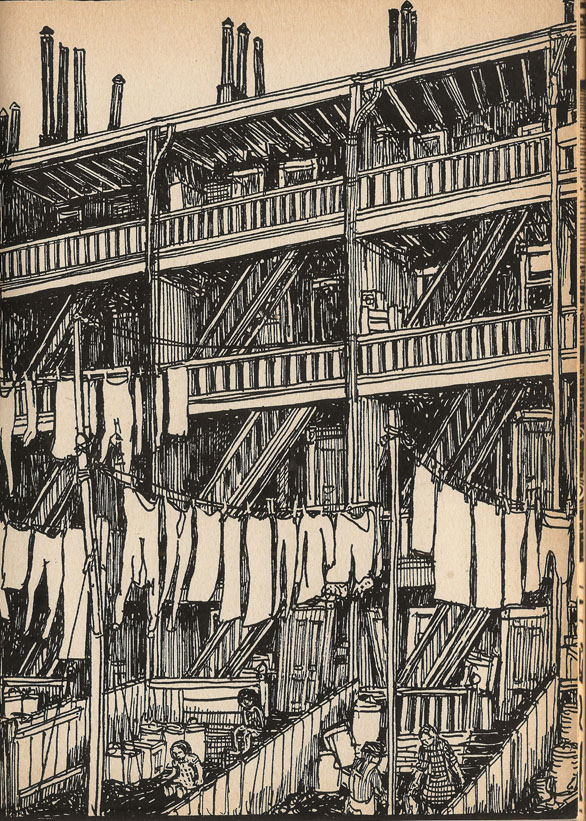

If you walk from front to back on any Chicago two-flat, you’re likely to notice one side is more comely. The fronts of buildings sport decorative flourishes such as limestone window sills, stained glass or arches. Likewise, the front interior staircases are often made of nicer-grade wood, sometimes with classy bannisters or carpets. The front is where you let your guests in and make an impression.

However, it’s a different situation at the back of the building, where you hang laundry to dry and haul out garbage. Originally, these back areas were used to receive milk, ice and other deliveries, even when residents weren’t home. Physical markers of those uses persist today; some buildings still have a small door in their back walls that once allowed icemen to place ice directly into kitchen iceboxes (fun fact: that’s why kitchens in these buildings are next to the back porch). And a few porches still have wooden outdoor “refrigerators.”

According to City of Chicago historian Tim Samuelson, these back porches came about partially as an outgrowth of Chicago’s characteristic back alleys. He said the extra room reserved for alleys also allowed extra space for large wooden structures such as porches. This is not the case in cities without alleys, such as New York City. Instead, those cities rely on the characteristic slim metal fire escapes, oftentimes on the front of buildings.

Samuelson also noted that back porches provided refuge from oppressive indoor heat in the days before air conditioning. Enclosed “sleeping porches” also used to exist in Chicago. And, in some cases, porches served as informal “sanatoriums” for sick patients.

But why wood?

That answer comes down to basic economics. Since Chicago was a center for the lumber industry, and wood has historically been a cheaper choice than metal or concrete, wood won out as the logical material of choice for two- and three-flats’ porches. In recent years, though, metal has been gaining traction.

Bob Fahlstrom also said attaching the required rear exit to the exterior of apartment buildings and homes allowed builders to maximize indoor space and value for renters. So from the beginning of these buildings’ construction, wood as the porch-building material of choice came down to money and ease.

Porch as fire escape: Does it work?

While wood structures seem an illogical choice for a means to escape fire, they are indeed effective — at least if you consider the distinction between making residents safe from fire and making living spaces fireproof. In fact, the revised City of Chicago building codes directly address the use and effectiveness of these wooden back porches.

Let’s start with the code. The city of Chicago has rules and regulations that allow wooden porches – especially those on three-flat apartment buildings – to act as emergency egress.

Regulations include:

- the porch must be behind a “fire-rated wall,” one made of fire-resistant brick or other material that burns at a slower rate compared to other materials

- porches may not be wider than ten feet, in order to prevent unwieldiness and collapse

- door frames leading to escapes must also be fire-rated to certain capacities.

Porches built from sturdy, pressure-treated wood themselves do not burn particularly quickly; it takes a fire about 10-15 minutes to burn through a wood door of thinner width than an average porch, which might take somewhat longer to burn.

Chicago Fire Department spokesperson Larry Langford said when it comes to fire safety, wooden porches work well enough, adding that the department has a typical response time of about 3 minutes and 40 seconds.

“The department is generally going to get there fast enough to make a good rescue if they get called in time on a fire,” he said.

Yet Chicago’s fire escapes are far from perfect; they are, after all, still flammable – and they’re often the site of the fire itself.

Langford said in the summertime, the city gets a few calls related to porch fires each week. The causes range from improperly disposed cigarettes that ignite trash or furniture, to Fourth of July fireworks that land on wooden slats. Of course, barbeques — both gas and charcoal — are culprits as well.

While winter porch fires are less frequent, Langford cautioned they often have malicious origins. He said arsonists are well aware of porches’ flammability, and they’ll use them as a sort of fuse to set an entire apartment building ablaze.

Langford also stressed the importance of smoke detectors as a way to increase the likelihood the fire department will be able to minimize property damage and insure safety.

Helpful in a fire, but …

Unfortunately, the physical history of Chicago’s wooden back porches is rapidly being lost. In 2003 a porch collapsed in Chicago’s Lincoln Park neighborhood and killed 13 people. After that tragedy, City Council toughened porch regulations, so building owners and contractors have been busy replacing porches, rather than just repairing them as they used to. These code revisions led to a veritable re-building boom; approximately ten new porch companies joined the existing five in the years following the collapse.

In almost all cases, the pre-2003 porches are original to their buildings, often dating back to Chicago’s construction boom in the early 20th century. Victor Gonzon, a Chicago porch-builder (working at 1-773-Porches), said that hundred-year-old porches are not uncommon, and that he’s aware of Chicago porches that may even be 120 years old.

Adam Lesniakowski, who’s been building porches in Chicago for four seasons with his aptly-named company Porch Builders, said he still spots lots of old and new porches around town that violate increasingly stringent city code — even though there’s a fleet of inspectors on the lookout. But code changes are among the reasons his own porch business is doing well.

The revised code doesn’t change the fact that the porches are flammable, even if they are safer for more occupants and used differently. When asked about any apparent irony in having flammable structures act as fire escapes, Lesniakowski thought about it for a minute.

“But our houses are built by wood, mostly,” he said. “And you’re cooking in the kitchen, you got candles. … Everything is by the wood.”

He’s right. Chicago buildings may have gotten better when it comes to fire safety, but the city will never be fire proof.

Keep up with Curious City’s latest via Facebook and Twitter.