When Church Meets State: Picking Apart Prayer in Aurora’s City Council

By Marc Filippino

When Church Meets State: Picking Apart Prayer in Aurora’s City Council

By Marc FilippinoAll too often, political coverage is fixated at the national level, especially so for hotly-debated, divisive issues. Think: War, trade, abortion. But some national political issues — some at the very heart of the national democracy — play out in local government, where much-needed conversations often never get off the ground and the status quo can remain unchallenged.

This is especially the case when it comes to the separation of church and state, the issue that inspired a question we received from someone who chose not to provide their name or contact information.

They asked: “We pray at the start of every City Council meeting in Aurora, Illinois. How is that even legal, and do other communities do that too?”

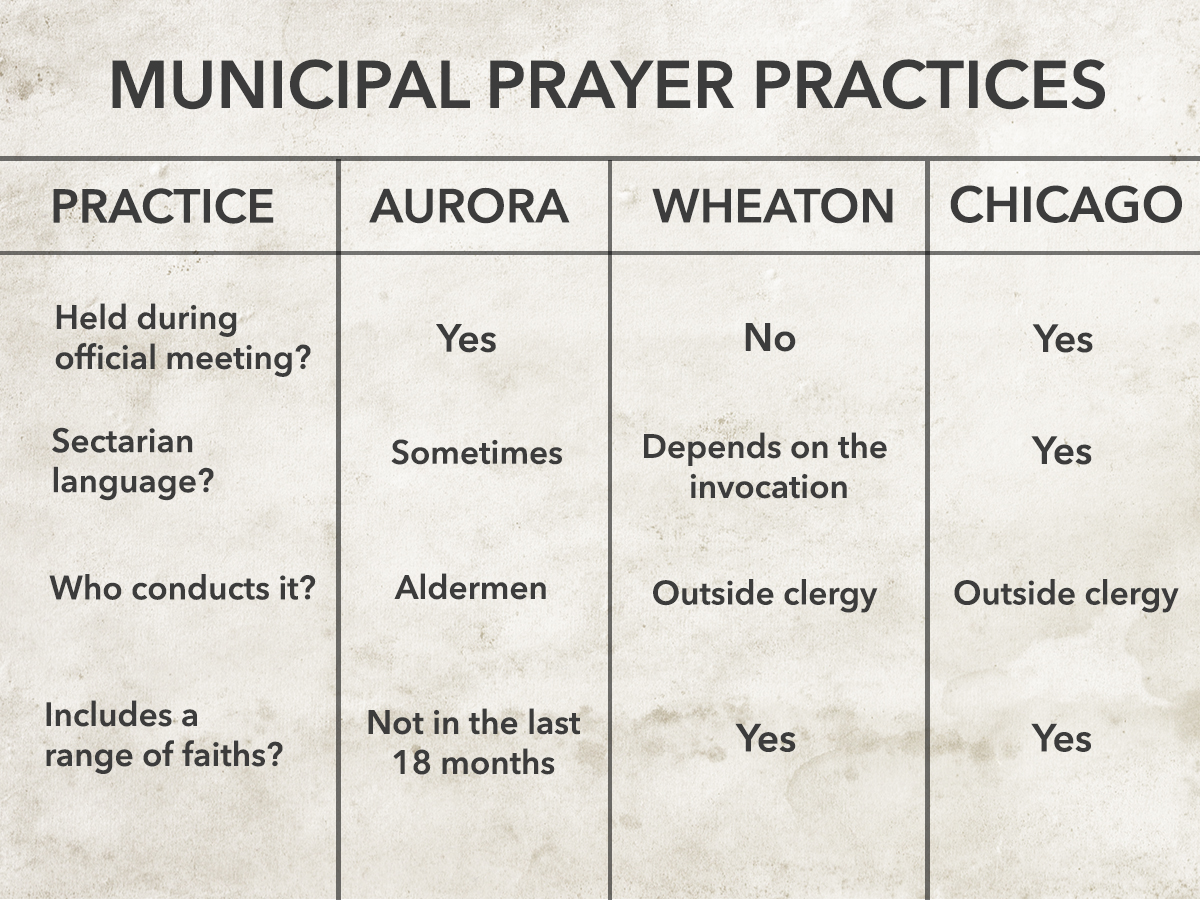

Aurora does indeed conduct prayers at the start of its council meetings. But before digging into the practice’s legality — here’s the short answer to whether other local city council’s pray, too: Yes. Yes, they do. Examples include Elgin, Addison, and Barrington. Chicago’s City Council holds invocations before it gets down to official business, as do the Illinois General Assembly and the U.S. Congress.

Before we get too deep into this story, we should clear something up: We’re not looking to answer whether Aurora’s local government — or any community’s, for that matter — should or shouldn’t have government prayer. We’re not trying to change your opinion about religion’s place in America. You do you.

We can point out, though, that how the city council in Aurora conducts prayer has the potential to raise flags in ways that another suburban community has had to deal with in the past. And we know this after talking with experts in the field who agree on one thing: Details matter. The prayer’s message, who gives it, when they give it and who’s required to listen are all touch-points, ones that can draw attention to fundamental values of diversity, inclusion and coercion.

‘Father we thank you for allowing us to come together for another city council meeting’

An hour west of Chicago, Aurora’s population of 200,000 makes it the second-largest populated city in Illinois. It’s religiously diverse, with many Christian churches, several Hindu and Buddhist temples, Jewish congregations and Muslim centers.

Its city council meetings start with roll calls and check-ins. After that, the mayor invites the council and the audience to stand for a moment of silence honoring active service personnel. That’s followed up by the Pledge of Allegiance and then an invocation.

The past 18 months of meetings are available online and show that invocations are typically performed by an alderman, usually Sheketa Hart-Burns. All are Christian-sounding.

The one from Oct. 25, 2016 is typical:

“Father we thank you for allowing us to come together for another city council meeting. We ask, oh God, that you be with us as we make decisions that affect this city. Be with the men and women of our armed forces as well as the men and women of our police and fire. We ask that you bless as we make decisions that affect this city and give us your encouragement daily. We ask this in your name. Amen.”

Bob O’Connor, who’d been on the council for 31 years until stepping in recently as interim mayor, says council prayer helps aldermen express their goals and feelings. O’Connor says in his time, the prayer has almost always been conducted by an alderman, though he recalls a few occasions where a member of the Jewish, Muslim and Christian community would take the lead.

The council’s invocations weren’t always done this way. In 1955, the city passed a non-binding resolution that invited the Aurora Ministerial Alliance to designate Christian or Jewish clergy to open the council meetings with prayer.

The Alliance is now defunct, and the practice of regularly inviting outside clergy to pray at meetings has been all but abandoned. Still, O’Connor says he hasn’t heard any complaints about the city’s current invocation process.

But Curious City has heard complaints.

One Aurora resident, Jim Schweizer, says he doesn’t see city’s diverse religious community equally represented.

“It’s only a Christian prayer,” Schweizer says. “The question is, ‘Why is it only one type of prayer? Why isn’t it a multitude of kinds of prayer?’ Buddhist. Jewish. Hindu. Muslim. There are many ways of communicating your religious beliefs. I think the way the city council is doing it now is only one way.”

An Aurora City Hall employee, who asked to remain anonymous out of fear of retribution in the workplace, says they’re baffled by the prayer. They’re concerned the practice violates the separation of church and state.

The council’s practice has supporters, too, however.

Resident Ellis Bailey says he thinks city council prayer is necessary.

“People need to be more aware of God in his leadership,” he says. “And with his leadership, it will allow us to come together.”

Rabbi Edward Friedman at Aurora’s Temple B’nai Israel says he doesn’t believe invocations are all that important. Friedman says before he moved to the B’nai Temple in September, he’d performed about six government invocations all over the country in his 41 years as a Jewish spiritual leader.

He says as long as aldermen are vague and inclusive enough to respect a community’s diversity in their prayer language, he has no problem with government officials starting meetings with an invocation.

“[Invocations] are kind of an optional component, they’re not really necessary,” Friedman says. “But if it’s important to your community, do it in a way that’s respectful to the diversity of the community. If you can’t do that, don’t do that.”

Based on what he knows about Aurora’s invocations, Friedman says the council could invite more people from the community. But as long as the prayers are kept non-denominational, it’s okay if the aldermen conduct the prayer.

“I think it’s nice to invite people from the community, indicating we are a broad community,” he says. “But it doesn’t have to be every time.”But what would a judge say?

Experts we’ve consulted about council prayer agree that details about legality and constitutionality come down to who performs the prayer and how the prayer is performed.

But these relevant details won’t get legal scrutiny unless a citizen or other party with legal standing challenges the practice in court, according to Chicago-Kent College of Law Dean Harold Krent.

After that, he says, a judge will consider practices including: timing of the prayer, who performs the invocation, and whether there are opportunities for different types of religions to participate.

After getting up to speed on the particulars of Aurora’s council prayer and hearing examples of prayers available online, Krent says the city’s practices would probably hold up in court.

“Well, it’s non-denominational. Everyone had to stand up, but it was in the context of the dignity of a moment of silence and the pledge of allegiance,” Krent says. “This does not strike me as on the more problematic end of the spectrum.”

However, he says a judge might be skeptical that Aurora’s aldermen always perform the prayer.

“There’s literally no separation of church and state in that situation,” Krent says.

Still, the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled the Establishment Clause isn’t always breached by prayer — even when conducted by city officials, or when a government hires its own chaplains to conduct the prayers. This was established in 1983, in Marsh v. Chambers.

In 2014’s Town of Greece v. Galloway case, the court also maintained that governments can lean towards sectarian prayer so long as they do not discriminate against minority faiths and don’t coerce people unwilling to participate.

If this seems vague and confusing, that’s because it is. Krent says the court left many questions unanswered, like how much inclusion is enough inclusion? One of the main conditions in Galloway was that municipalities couldn’t show favoritism toward one specific religion, and they should offer clergy of different faiths the opportunity to participate.

A complaint, a review and a prayer makeover

Not every complaint turns into a court decision, though. Sometimes communities respond to complaints by making their invocations more accommodating.

Twenty miles east of Aurora, the city of Wheaton used to have an invocation at the start of its council meeting. Wheaton Mayor Mike Gresk says his would operate similar to Aurora: They would call the roll, conduct the Pledge of Allegiance and then have an invocation. Unlike Aurora, Wheaton would call in a member of the clergy to conduct the prayer.

In 2009, a member of the community told Gresk they felt uncomfortable when clergy would often call upon Jesus during the council’s invocation. Gresk says the city had never heard a complaint like that before and didn’t know how to handle it. The city took action after receiving a formal complaint from the Freedom From Religion Foundation, a Wisconsin-based nonprofit that promotes the separation of church and state.

Wheaton then gave its invocation process a makeover, but it didn’t ditch prayer entirely. Gresk says aldermen wanted to somehow represent many residents’ religious values.

“It’s a very thoughtful prayer community,” he says, adding that he recently received a note from a neighbor who said they were praying for him. “I value it, and I’m ceaselessly amazed and impressed there are people who are concerned enough they want to pray for me.”

The compromise involved changes to the invocation that would be less coercive to citizens who didn’t want to pray during the council meeting. One change involved conducting prayers and the Pledge of Allegiance before the official start of meetings. The prayers are not in the meeting minutes, and they’re not taped or available online. They’ve had a range of invocations, including an atheist invocation. Gresk says he has even seen people leave the room to avoid the prayer.

“We have people who come to the formal meetings and they simply don’t rise [for the pledge],” Gresk says. “Well, that’s fine. If you don’t support an organized religion that’s great. If you don’t want to stand for the pledge, you’re an American.”

Additionally, the city passed an ordinance formalizing the city council’s invocation process.

Our legal expert Krent says a judge would probably rule Wheaton’s council prayer “perfectly permissible.”

“It gives you a clear indication that if you wish to engage in the prayer activities then you may do so, but if you wish to just transact legislative business you may do so as well,” he says.

But Rabbi Friedman says having an informal prayer isn’t a foolproof solution. In fact, he thinks it could pose a bigger threat to diversity in the long run.

“There’s a greater opportunity to be non-inclusive because it’s not official,” he says. “It’s a way of saying, ‘We can avoid the consequence of the law.’”

Aurora’s silent prayer opponent

Both Town of Greece vs. Galloway and the Wheaton transition began with a resident complaint. In Aurora, Mayor O’Connor says he’s heard no complaints.

Or, maybe people just don’t know about the city’s invocation process. Wheaton Mayor Michael Gresk points out that very few people actually attend council meetings. Who is going to assess the prayer if no one knows it exists?

“Unless it’s your ox being gored, unless it’s immediately impacting you, people tend not to come,” Gresk says.

But, Krent, our legal expert, says people might not be speaking up in Aurora because they fear being ostracized by the community. He says the anonymity from our questioner raises potential red flags about how Aurora handles this issue.

“The fact that they came to [Curious City] anonymously does highlight the problem,” he says. “The fact that they are, for whatever reason, right or wrong, frightened to use the political channels open to them, does at least plausibly suggest the problem here of feeling coerced by this practice.”

The Aurora city hall employee who requests to stay unnamed confirms this feeling of coercion. They fear if they speak up, their job could be in jeopardy. They say Aurora is the type of government where everyone is expected to fall in line.

In light of these developments, Curious City asked for a follow-up interview with Mayor O’Connor. He declined. A city statement reads:

Immediately prior to a moment of silence and the Pledge of Allegiance, the Aurora City Council opens its meetings with prayer conducted by an alderman. As previously stated by Mayor Robert J. O’Connor this is a practice that has been held for decades and does not violate any laws, as confirmed by our Legal Department.

If a City employee is uncomfortable with this practice that matter certainly has not been brought to the attention of the Mayor’s Office by the employee on their own regard or by a manager on behalf of the employee.

Because the meeting is structured in the aforementioned way where all business is conducted after prayer, a moment of silence and the Pledge of Allegiance, any employee can still fulfill their duties by coming into the Council Chambers after the opening section on the agenda.

Prayers at the beginning of a City Council meeting does not violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment where there is no “indication that the prayer opportunity has been exploited to proselytize or advance any one, or to disparage any other, faith or belief.” Marsh v. Chambers, 463 U.S. 783, 794-95 (1983).

This feeling of coercion Krent alludes to might be enough to maintain the status quo. Our source in city hall says they’ve discussed how uncomfortable the prayer makes them with other members of the community. But they say residents who feel strongly enough about this issue are often dependent on city council.

Aurora’s city council, like any legislative branch, wields power: They handle smaller requests like adding more street lights or installing a yield sign on a street corner. But aldermen also approve gas taxes, pass local regulations and vote on the city’s budget. Who wouldn’t want to stay on their good side?

Based on the city’s statement and Mayor O’Connor’s comments, it’s unlikely Aurora will revisit its invocation process anytime soon. Perhaps our questioner will have stoked a discussion ahead of the city’s mayoral election in March.

But … perhaps not. As our source in City Hall says: No mayor wants to be the mayor that gets rid of city council prayer.

Marc Filippino is the intern at Curious City. Follow him @mfilippino.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the location of Aurora relative to the city of Chicago. The correct location is an hour west of Chicago.