Artists turn up volume on gun violence debate

By Alison Cuddy

Artists turn up volume on gun violence debate

By Alison Cuddy

Critics have debunked that very notion as both a myth and an oversimplification, one that can obscure the way black communities do rally to respond to neighborhood violence, or how whites do sometimes resort to racist stereotypes in talking about criminality.

Now another reaction to this idea of black-on-black violence can be found at KKK - Kin Killin’ Kin, a new exhibition at The DuSable Museum of African American History.

The show is by James Pate, an artist based in Dayton, Ohio. He believes blacks may well respond more vocally when white people kill blacks, a response he attributes to a psychological state that is a “residue” of historical experiences like lynchings: “It’s a sensitivity that to me is unreasonable,” said Pate. “But I think that’s where it comes from, this imbalance in the uproar.”

But the more provocative aspect of Pate’s work may be the way he himself represents black people.

In the wake of Trayvon Martin’s killing, to show gang members clad in the robes of white racist vigilantes is a challenge, to say the least. But Pate said he has no choice.

“It is difficult for me to react any other way as an artist,” said Pate, who’s been making these images since 2000. “It is extreme to me, so I decided to do something as extreme as I can imagine, within what I do as an artist, stylistically.”

Pate said his art stems from conversations in the black community, “about how black-on-black violence has replaced the KKK form of terrorism. I decided that to sort of curb my blues, I would illustrate that sentiment and show them going at it and some of the aftermath of these acts.”

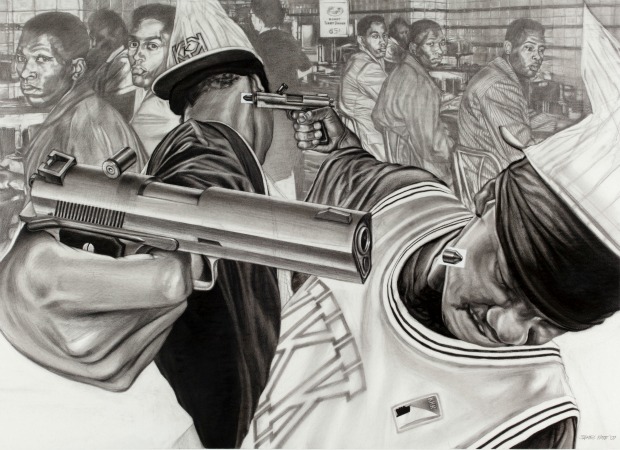

Pate’s images also juxtapose contemporary violence with action from other historical moments. In the foreground of Your History III, two young men drawn in bold relief shoot each other with semi-automatic pistols. On either side of the frame, drawn in fainter tones, there are rows of young men, seated at a restaurant counter, who appear to be witnesses to the shooting.

Pate said his reference to the lunch counter protests of the Civil Rights Movement poses a question: “What in the world happened between that ideal and that mentality, and that sacrifice - and this?”

Pate’s images cite other historical figures, from black Union soldiers to Adolf Hitler to Jam Master Jay of Run-DMC. There are even allusions to the crowds who came out to watch lynchings during the height of the Klan’s raids, depicted here as passive witnesses to violent acts.

That passivity comes across as a critique of community indifference or action. But Pate said his work also reflects “a frustration that I’m experiencing because I don’t know what to do, and all I do know is that in art I can go there and turn my volume up a bit.”

Pate said reaction to the work (which was shown previously in Ohio), ranges from recognition to anger, the latter especially from blacks who feel he’s airing dirty laundry. In response, Pate said that laundry was hung out long ago.

Carol Adams, who heads the DuSable and brought the show to Chicago, agrees.

“If the show offends a little bit, well, we’ve been way too polite,” Adams said. “It is a madness, and it is time to scream.”

Local audiences already seem to be paying attention. At the exhibition’s entrance, visitors are invited to write the names of deceased friends and family on small manila tags and attach them to stretches of chain-link fence installed for the show. Even before the show opened, museumgoers started filling out the tags - there are already more than a hundred on display.

‘KKK - Kin Killin’ Kin,’ The DuSable Museum of African American History, through Aug. 3. James Pate will give a gallery talk on Thursday, Aug. 1, from 6:30 - 9 p.m.

Cheryl Pope is another artist turning up the volume around the violence debate in her show Just Yell, which is at the moniquemeloche gallery through Aug. 3.

The show’s name references the first cheerleaders, known as “yellers,” who in the late 19th century got up in front of crowds and started to call out cheers.

Both the structure of Pope’s show (which is a collaboration with students from public schools across the city) and the works she’s created (which include a yearbook, a spirit stick, and a large wall-mounted varsity patch) are efforts to invoke the team mentality and powerful spirit of the yellers.

But in place of sports cheers, Pope offers what she calls “testimonials”: the words of students, who, in response to prompts from Pope, wrote about their reactions to violence and what that makes them want to “yell.”

“The schools don’t always have the time or space or means to create opportunities for grieving or processing these losses,” said Pope. “I wanted students to feel empowered by the way they react so we could have those conversations.”

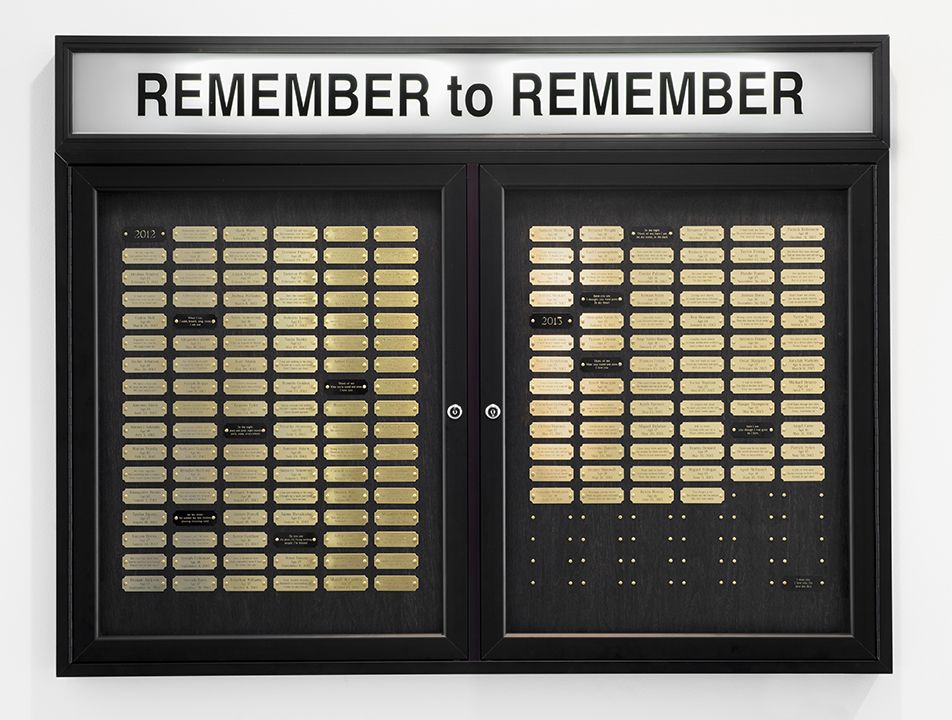

But like Pate, Pope’s exhibition also contains a provocation: The colors scheme she’s used across the objects in her show are those of local gang The Latin Kings: gold, black and white. And she represents gang culture in other ways. In Just Yell ‘13: A Guidebook for Yellers, pictures of both victims and gunmen are displayed in tidy, yearbook-like rows.

Pope said that in researching The Latin Kings, she found remarkable parallels between their “philosophy” (which is defined by their five-point crown) and the ideals of school or team spirit, things like love or respect or community. In other words, gangs promise “everything young people are asking for.”

“I wanted to be mindful and not glorify, but make visible that parallel, or that confused space, which can exist for young people,” said Pope. “Where gang affiliation can offer the satisfactions of being on the same team, or sharing a goal, or knowing someone has your back.”

Despite their different styles, there are remarkable parallels between Pate and Pope.

Both use inflammatory imagery not just to provoke viewers but to reveal their own emotional connections to the issue of violence (a perspective which partly results from working closely with young people, Pate as an artist-in-residence at public schools, Pope at the James R. Jordan Boys and Girls Club near the United Center).

Both are committed to a continuing exploration of violence: Pate has moved into color images and Pope’s next project involves how people grieve for their communities.

But by forcing together supposedly disparate groups - draping gang members in Klan robes or decorating a school spirit stick in gang colors - each artist has created a different space to discuss violence.

Once you sort through that confusion of images, the space can come across as absence — something painful and awful and empty. But it also contains potential, as a place from which it might be possible to do or say - or even yell - something new.

‘Just Yell’ is at the moniquemeloche gallery through Aug. 3. On July 27, Pope has invited what she calls “game players” - those actually on the court rather than yelling from the sidelines - to the show, including aldermen, DCASE Commissioner Michelle Boone and Mayor Rahm Emanuel.

Alison Cuddy is WBEZ’s Arts and Culture reporter and co-host of Changing Channels, a podcast about the future of television. Follow her on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram