Blacksmiths: The ‘Plastic Surgeons’ On Chicago’s Payroll

By Dan Weissman

Blacksmiths: The ‘Plastic Surgeons’ On Chicago’s Payroll

By Dan WeissmanEditor’s note: This story was first published in 2015. The city currently employs 21 blacksmiths, all working for the Department of Streets and Sanitation. The city’s budgets for 2017 and 2018 provide for 24 blacksmiths positions, but the city has no current job listings for blacksmiths.

Our questioner, Joel, describes himself as a nerdy, curious guy who likes playing with data. When the City of Chicago published its payroll data, he thought it would be fun to look and see what was there.

And he did find a surprise.

“I was just scrolling through, and I saw ‘blacksmith,’” he recalls. As in, the city employs one. “Like, did my eyes deceive me?”

A couple of mouse-clicks later, he found out how many blacksmiths the city employs. Then, he posted on Curious City:

The city just released their budget and employee info on the open data portal. I noticed that Chicago has 20 blacksmiths! What do they do?

The word “blacksmith” conjures up an image of glowing-hot metal getting pulled from a big furnace and pounded into some usable shape — maybe a horseshoe — on an anvil. Maybe the light in this image comes from the furnace flame, since blacksmithing thrived for millennia before electric lights. The whole scene seems ancient, or at least old-fashioned.

So, why would the notoriously cash-strapped City of Chicago employ more than 20 of them, at salaries of about $90,000 a year?

That’s the essence of the question we got from Joel. He’s asked us not to use his last name because he works for local government, and his boss, understandably, thought the question might make political higher-ups uncomfortable. Again, Joel promises he wasn’t being snarky, just curious. Still, the city’s mounted police unit only has about 30 horses: How many horseshoes could they need? It turns out, there’s a perfectly-reasonable story — or, almost-perfectly-reasonable — and it has nothing to do with horseshoes. (The city hires a farrier for that trade). In pursuing it, we did find a living link from the ancient art of blacksmithing to the city’s operations.

The city’s plastic surgeons

So, then: What do the city’s full-time blacksmiths actually do? To find out, I visit blacksmith Luke Gawel at his work — a city plant at 52nd Street and Western Avenue, with two giant repair bays for trucks.

Here’s how Gawel describes the job: “We are like the plastic surgeons of the City of Chicago. The only difference is we haven’t gone to medical school.” Their patients are the city’s trucks: garbage trucks, ambulances, and fire trucks. But like people, these patients don’t take off-the-shelf parts. “Every truck is almost custom,” says Gawel. “The city has them custom-built for their specs. When they get smashed, when they get damaged, you can’t just go online … [to] Amazon and get a panel. You have to build it, and then you have to install it.”

On the day I visit, Gawel has picked a small job to demonstrate what he does: welding a step back onto a garbage truck — the kind a worker rides on, at the back.

He grinds off some paint and grime, and sets up his MIG welder. Then he applies the heat. Less than a minute later, he’s done. “It’s good to go,” he says. “You can hang on it.”

Except: Grease on the bottom of the newly-welded step is on fire. “It’s probably a little warm to touch,” Gawel admits. “You can fry an egg on it, but — you let it cool off, throw some paint on it, and that’s it.”

This is a small job, but Gawel spends a lot of time on bigger ones: replacing the sides of trucks, the floors, the big mechanical elements in back of a garbage truck that smush the trash. If you can’t repair these big, basic parts, you’d have to junk the whole vehicle.

“At the end,” he says, “we do save the city a lotta money.”

With a city fleet that includes 477 garbage trucks, 203 fire engines, 101 street sweepers, and 122 ambulances, Gawel and his colleagues have plenty to do. In the winter, the city adds 333 salt spreaders and snow plows to the fleet — what Gawel’s boss calls “wear items” — and twenty full-time blacksmiths isn’t enough. The overtime numbers are insane: more than $65,000 just for February 2015.

Is ‘blacksmith’ the right word?

Given that the city’s “blacksmiths” clearly spend the vast majority of their time welding, why not dispense with calling them such? After all, the number of workers employed as blacksmiths is clearly on the downswing. The number of full-time blacksmiths in the U.S. peaked about a hundred years ago, when the U.S. Census Bureau counted 235,804.

Forty years later, in 1950, the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that fewer than one in five of those jobs remained. Following another thirty years of decline, the BLS found that three-quarters of those jobs were gone too, and it stopped counting.

Until he came to work for the city, Luke Gawel would not have counted himself among this ancient and dying breed, although the work he did in previous jobs was quite similar to what he now does for the city. In fact, he stumbled onto this job because he found the job title just as incongruous — just as curious — as Joel did.

“One day, I was just scrolling through the city’s website, and I saw a blacksmith,” Gawel recalls. “I was like, ‘What? Blacksmith!?’ I couldn’t believe it.”

He clicked on the job description and, as it happened, it described the work he was already doing in a private shop: using plasma cutters, acetylene torches, and welding tools. Actually, the job description also mentions heating metal in a forge — a blacksmith’s furnace — but the city hasn’t owned a forge for years. “We had one downtown, when I first started,” says Gawel’s colleague Chuck Miggins, a city blacksmith since 1999. “But we never used it, and it’s obsolete.”

So, why does the City of Chicago still use the title “blacksmith”?

Leo Burns, Managing Deputy Commissioner for the Human Resources Department agrees it’s a good question. But, he says, it’s still the official job title. “It’s in our bargaining agreement. We have an agreement with the International Brotherhood of Boilermakers.”

You could translate that answer as: bureaucratic inertia. Changing it hasn’t come up, and could be a hassle. However, Burns says the outdated title is not causing the kind of problem that would get his attention.

“I don’t remember anyone saying we need a new title because we’re not attracting candidates,” he says.

Last of the real city blacksmiths?

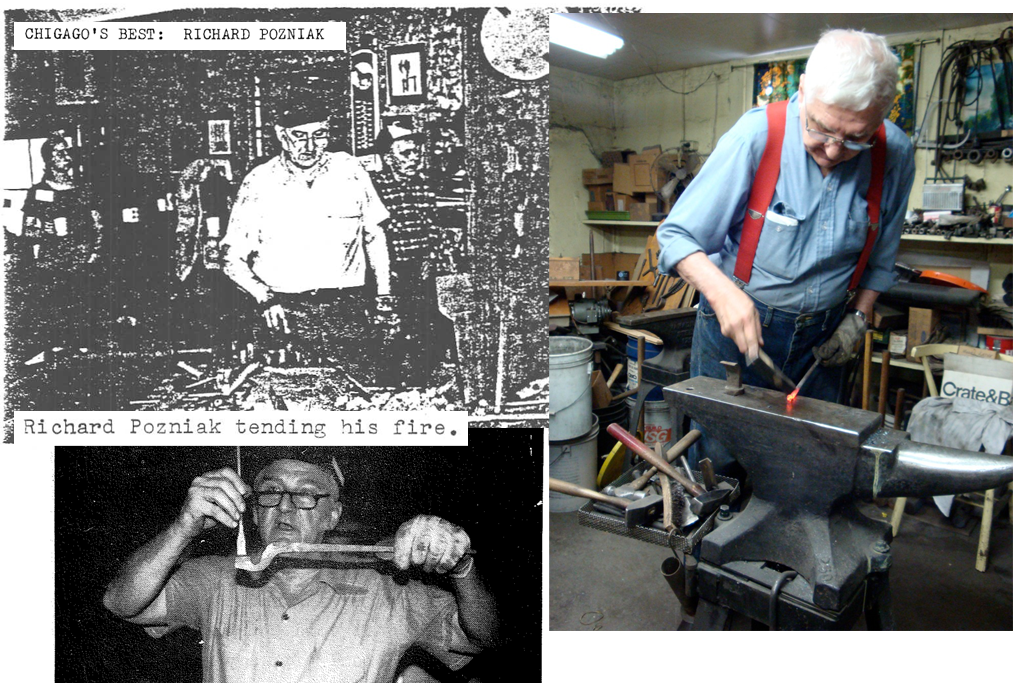

I did talk with someone who worked the “obsolete” forge that city blacksmith Chuck Miggins remembers — a person who connects Miggins and Luke Gawel with the ancient image of a man (or a Roman god or Celtic goddess) pounding on glowing-hot metal.

“We always had somebody working on the fire, who worked the forge,” says Richard Pozniak, who retired from the city’s blacksmith force in 1993. The man on the fire would “do things like straighten bumpers, make chains, special hooks,” he says.

“I was one of the last ones working on the fire.” When Pozniak signed on with the city in 1950, old-school blacksmiths were already almost gone.

“By that time they only had one blacksmith,” he says. “One real blacksmith — that worked on the fire.”

Just one — out of what he remembers as 30 or 40 city blacksmiths. The rest were already doing basically the same work that Luke Gawel and Chuck Miggins do today: cutting pieces with gas torches, joining them with welds. That’s how Richard Pozniak spent his first ten years as a city blacksmith, but working on the fire had always been his goal. When his chance came, about ten years into his service with the city, he took it, and kept it till he retired.

A few years afterwards, the city idled its forge, but Richard Pozniak kept working his own fire — in a shop in his basement — making decorative items and tools. Until now. At age 85, he’s closing up shop.

“I can no longer even get down to the basement to get around,” he says. “It’s an inevitability I had to accept.”

Over the years, peers in the blacksmithing world had referred to him as a master. Among the tools that Richard Pozniak made are tongs of his own design, which artisan blacksmiths and hobbyists around the country now make and use. They’re known as Poz tongs.

For more about Richard Pozniak, check out this story about him from the show Studio 360, by his son-in-law, radio producer Peter Clowney.

Dan Weissmann is a reporter and radio producer in Chicago. Follow him @danweissmann