Chicago goes dry

By John R. Schmidt

Chicago goes dry

By John R. SchmidtThe year was 1920. At midnight, as the calendar clicked over onto January 17, Prohibition became the law of the land. Chicago’s reaction was a big yawn.

Okay, we all know about Chicago in the Roaring Twenties. We know that the city became the bootlegging capital of America. We’ve seen the gangster movies.

But that was all in the future on that January evening in 1920. The crowds at the taverns were no larger than on a typical Friday. When the clock struck 12, the patrons downed their drinks and left, the bartender locked up … and that was that.

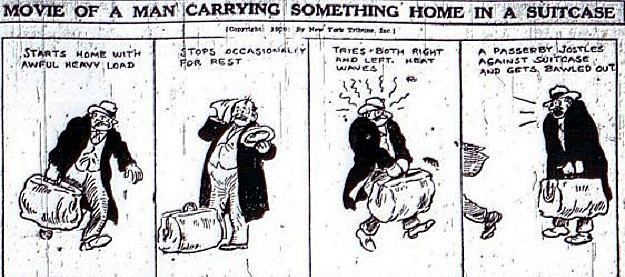

The Prohibition law said that the manufacture, sale, or distribution of intoxicating beverages was illegal. However, people were allowed to have booze and beer in their own homes for their own use. They could keep all the beverage they wanted, as long as they bought it before January 17.

So Chicagoans began stocking up. Liquor stores had raised prices, but the public kept buying. In the final days, autos and trucks were also in demand–for some people, the first time they drove a car was the day they hauled their liquor home.

Major A.T. Dalrymple was the local head of Prohibition enforcement. He announced that people would have ten days to report the exact quantities of beverage they held in their homes. That was a matter of law. There should be no fear that government agents would raid a private residence.

![Major Dalrymple [left] after a raid (Library of Congress)](https://s3.amazonaws.com/wbez-cdn/legacy/image/1-17--Dalrymple%20and%20aide%20%28LofC%29.jpg)

![Major Dalrymple [left] after a raid](https://api.wbez.org/v2/images/b10b0da6-da6a-4d64-80c1-566f29947efe.jpg?width=900&height=599&mode=FILL)