It was the biggest celebration of a single person Chicago had ever seen. Over 3 million people lined the city’s streets. The date was April 26, 1951.

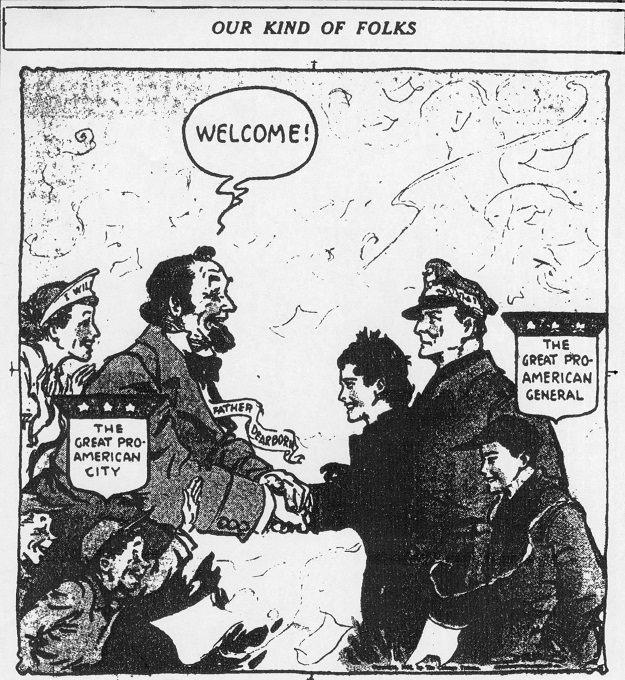

After 14 years on foreign soil, Douglas MacArthur was back in the United States. America’s General had returned. And the city went wild.

MacArthur was a national hero. He led U.S. forces to victory in the Pacific during World War II. When the Korean War broke out, he had turned back the enemy advance at Inchon.

But now that war had become a stalemate. MacArthur thought President Truman was being too cautious. When the general’s views became public, the president relieved him.

That created a sensation. Truman was a very unpopular president in 1951. Most of the country thought he’d made a mistake sacking MacArthur.

The general had gone to Washington to deliver his report to Congress. Now, with his wife and young son, he was making a triumphal progress across America.

MacArthur’s plane touched down at Midway a little after noon on April 26. City officials greeted him, then he was off in a motorcade to downtown. A long, meandering route was used, so that the maximum number of people could witness the general’s passage.

The main event was an evening reception at Soldier Field. The crowds began gathering at 5:30, three hours before the general was to arrive. While they waited, they were entertained by drum and bugle corps, color guards, marching units, and military bands. Veterans’ groups and ROTC squads dominated the proceedings.

As the skies darkened, the beacon atop the Palmolive Building–two miles away–was focused on the field. Finally, MacArthur made his entrance. The assembled throng cheered. He acknowledged the greeting, then spoke.

The general called for a realistic end to the Korean conflict, with a minimum loss of American life. He said the U.S. had no clear war policy. In case anyone doubted what he thought, he said that our goal should be “victory over the nation and men who, without provocation, have attacked us.”

Applause interrupted him 19 times. Concluding, he declared: ”[Even] without command authority or responsibility, I still proudly possess the greatest of all honors and distinctions–I am an American!”

The thousands rose to their feet and cheered again, long and loud. Then came the fireworks display. Then it was over.

The next morning MacArthur was gone. He left behind a dazed and dazzled Chicago. And in the long sweep of history–by his conflict with President Truman–he left behind a controversy that is still debated.