If your taste in fashion tends toward the dramatic, glamorous and expensive, then hang onto your hangers! A new exhibition at the Chicago History Museum may well give you a serious case of wardrobe envy.

Inspiring Beauty: 50 years of Ebony Fashion Fair is a history of the traveling charity fashion show. Launched in 1958 under the auspices of Chicago-based magazines Ebony and Jet, the Fair brought the latest and best European couture to black men and women across the United States.

The museum is exhibiting more than 60 garments, covering five decades of high-end clothing and dozens of designers. Pieces include day looks, head-to-toe fur ensembles and drop-dead gorgeous evening gowns. The high priests of French couture (Dior, Lacroix, St. Laurent) are represented, but so are American designers, including Bill Blass, Patrick Kelly and Todd Oldham.

If the collection sounds eclectic and overwhelming, it is! But there is a governing principle to guide you: the discerning eye of Eunice Johnson.

Johnson was a devotee of fashion, art and beauty long before she took over directing and producing the Ebony Fashion Fair in 1963. Another employee of the magazine was in charge before that.

Johnson was born into a well-to-do family in Selma, Ala. She earned her masters degree — and met her husband, John H. Johnson — at Loyola University in Chicago. They started the magazines together, but it was Eunice who came up with the name Ebony.

An important accessory — her bottomless pocketbook — first gained Johnson entry to the fashion houses of Europe in the late 1950s. At that point she was an unknown, representing a magazine that didn’t have the international reputation of Vogue or Harper’s Bazaar. She was also the rare black buyer.

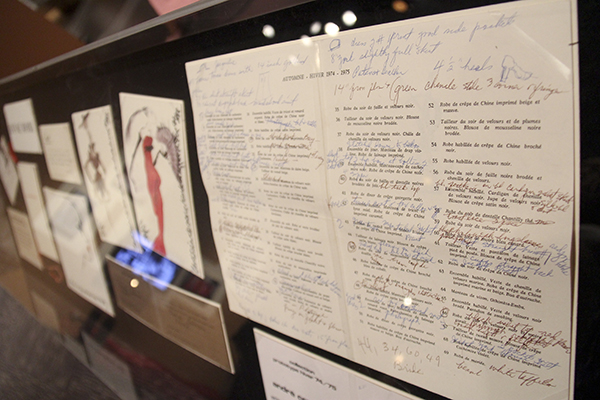

Johnson bought a lot of items for her own wardrobe, so one of the exhibition’s many pleasures is to see ephemera from that process, such as her scribbled notes and drawings. But when it came to the Fair, though, she took a more wide-ranging, adventurous approach.

Johnson was obviously drawn to dramatic red-and-black ensembles. Consider Pierre Cardin’s medieval-inspired tunic, as well as African-American designer Rufus Barkley’s fringed day dress.

The collection also emphasizes bold patterns, bright colors and interesting textures. For an example, check out Christian Dior’s 1968 fuchsia pant suit festooned with gold accessories and purple coat.

And the silhouettes are all over the map. Inspiring Beauty features plenty of curve-hugging dresses and sculptural gowns, including a gorgeous gold one by Emanuel Ungaro, one of Johnson’s favorite designers. These are not clothes for the faint of heart.

Joy Bivins says that was intentional. “When the fashion fair started, black women were quite discouraged from wearing bold, bright colors,” said Bivin. “And what she did was put the brightest yellow on the darkest brown model’s skin, to make a statement that women in the audience shouldn’t be afraid to draw attention to themselves throughout the use of bold color.”

Bivins added that, though Johnson wanted to bring “what was fashionable at the moment” to the Fair’s audiences, she was also “creating a fashion fantasy.” Attendees at the Fair (which traveled from big cities like New York to small towns such as Joliet, Ill.) might actually buy clothes, but they were also there to learn, to see ideas of “how to dress yourself, or how to develop a personal style.”

Aspirational elements are also embedded in the outfits. Bivins said Johnson thought fur “signified success,” so there are plenty of ensembles using that material. And if Johnson didn’t see what she wanted, she made it happen.

She once presented a silver, hooded evening gown by Bob Mackie as a bridal outfit and asked the designer to create an ostrich feather stole to complete the look. And because she had plus-size models on her runway, she persuaded Todd Oldham to make one of his gowns in a size 20. However, Bivins said, it took Oldham a month to consider the idea and Johnson had to provide the material.

Of course the models on the Fair’s runways were black, and often wore black designers, including Barkley, Patrick Kelly and Stephen Burrows. So in a period when fashion was segregated, Johnson provided a launching pad for many.

Bivins explained “When you first started to see black models on the covers of mainstream magazines, there wasn’t one that hadn’t already been in Ebony magazine. That was the platform.”

Bivins, whose background is African American history, says the Fair’s commitment to advancing black life and culture broadens the Fair’s significance.

Though a fashion show could seem less important than the fight “to get a seat at the Woolworth counter, it is still part of a larger struggle for visibility within the culture of a middle class,” said Bivins. “Where else do they get a platform to show themselves as beautiful? As glamorous? As sexy? And so Ebony Fashion Fair, for me at least, intervenes at a moment when the imagery is being contested.”

That sense of respect — that black audiences were worthy of inhabiting these materials — is reflected in the overall design of Inspiring Beauty. Like a fashionista’s well-organized closet, the lighting and backdrops convey glam, but they do so subtly; too much oomph would have detracted from the outfits.

It all made me wonder why a city with so many fabulous museums doesn’t have a major fashion collection on permanent display. Bivins said Johnson’s vast archive likely won’t get that treatment, as couture isn’t made to hang for years. Incidentally, Inspiring Beauty represents only a fraction of Johnson’s entire holdings.

But hopefully this show, which Bivins say may travel, will nonetheless spread Eunice Johnson’s reputation as one of America’s first ladies of fashion, as well as a pioneer in seeing clothing as a tool to advance civil rights.

Inspiring Beauty: Fifty Years of Ebony Fashion Fair is at the Chicago History Museum through Jan. 5, 2014.

Alison Cuddy is WBEZ’s arts and culture reporter. Follow her @wbezacuddy and on Facebook