Finding Chicago’s first maps

By Robin Amer

Finding Chicago’s first maps

By Robin AmerMiriam Reuter wants to know how Chicago’s coastline has changed over the decades. The Albany Park resident used to live in Rogers Park, and walked her dog – a terrier-mix mutt named Sydney – on the beach a lot. “I’d be interested to know if it was man made or originally there,” she told us. “The lake and Chicago are inseparable.”

Technically we could go back several million years to answer Miriam’s question, to the glacier that carved out the Great Lakes. But Miriam seemed most interested in the period of human intervention, and the time when Chicago was officially a city.

That’s fine by me, since one of the things I follow closely is the history of our area’s built environment. The lake was made by nature, but humans have shaped the coastline to suit our own needs – just look at the fancy new harbor at 31st Street or Streeterville, Captain George Wellington Streeter’s audacious landfill settlement. I love how you can sometimes see little glimpses of the past in the present, so I wonder, too: What did the coastline look like before humans messed with it, even in its broadest contours?

First we had to figure out which maps were available.

We figured we would have to find the very first maps of Lake Michigan, and move forward in time from there. So we started looking, and it turned out we weren’t the only ones interested in the history of Chicago’s coast. A few weekends ago, a rowdy, rag-tag group of history buffs set out to retrace part of the original coast of Chicago – in canoes on wheels.

Paul Durica is a PhD student at the University of Chicago and the founder of Pocket Guide to Hell, which offers “guerilla walking tours” and eccentric reenactments that showcase Chicago history. He’s reenacted the so-called Battle of Halsted Viaduct and the Haymarket Riots, and this time, he and his cohorts reenacted the journey that Jacques Marquette, a French Jesuit missionary, and Louis Joliet, a French Canadian explorer for hire, made through the Mississippi River delta 1673.

It was great fun to see these folks tramping through Streeterville with fake beaver pelts in tow, even if their route wasn’t 100 percent historically accurate. His actors snaked their way from Water Tower Place down to the park at Illinois and McClurg, whereas, according to Durica, Michigan Avenue originally represented the eastern-most portion of land.

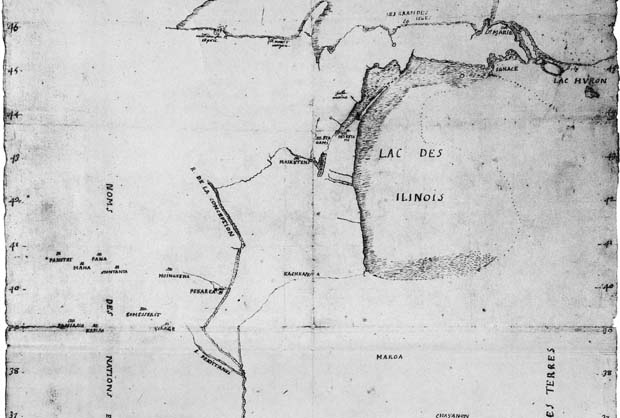

Still, we learned some important stuff from Paul in the quest to answer Miriam’s question: Although Marquette and Joliet made the first European maps of the Lake Michigan, they lost their maps and journals when their canoe tipped over during their return journey. Joliet later recreated some of these maps from memory, but they weren’t considered very accurate.

After a little digging we found Joliet’s map, now housed at the maps division of Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.

Yeah, it’s true – Joliet’s remembered depiction of North America isn’t especially accurate. (Note the distance between Virginia and the Great Lakes). But you can see his recollection of Lake Michigan and that spot where the Chicago River peeks out of the lake. He and Marquette first found the spot where the river meets the lake, the spot where Chicago would one day be.

Pretty cool, but just to be safe, I didn’t want to presume that Europeans were the first to map the coast, or the first to alter it. Perhaps Native Americans had created their own maps. To suss this out, I called Bob Morrissey, an assistant professor of history at University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana and an expert on the French colonial period. He specifically studies the way that Europeans interacted with and shared knowledge with the Native Americans.

Morrissey was helpful, as he explained how Marquette spent years studying the Illinois language. Although he wasn’t fluent, he was proficient enough to converse with the Illinois tribes and ask them for directions.

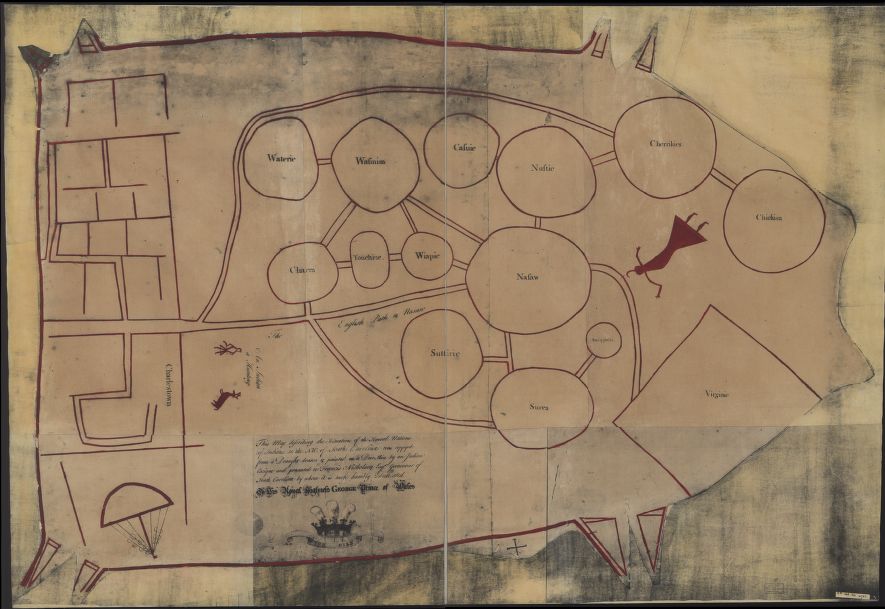

Morrissey showed me another map that may slightly pre-date Joliet’s map, known as the Marquette manuscript map. Referencing a map expert named Sarah Jones Tucker, who compiled an atlas of these old maps in the 1940s, Morrissey said this map was probably drawn by Marquette’s own hand, based in part on information he got from the Illinois.

“I imagine [Marquette] was probably drawing drafts of this as he went and asking for assistance from Native Americans that he met to draw the location of villages,” Morrissey said. “Now his concept of a map was very different from a native concept of a map. Drawing three-dimensional space onto a two-dimensional piece of paper was not something Native Americans and Europeans shared.”

When I asked Morrissey to explain this further, he alluded to a well-known map created by a Native American around the 1720s of the southeast portion of America. “The few spatial maps we still have drawn by native peoples during that period, rather than a picture or representation of the land, it’s a picture or representation of people on the land,” Morrissey explained. “Their positions relative to one another matter as much as their positions relative to the physical space.”

So, in the quest to answer Miriam’s question, we now know this: Native Americans may have mapped the Great Lakes region, but their maps follow a different set of priorities and cultural/spatial logic than the geographic maps we’re used to today. Still, Marquette and Joliet used the Native American knowledge base to explore Lake Michigan and create the first European maps of the region. And even though we’ve lost those original maps, the recreations give us a glimpse of their view of the landscape.

These early maps though depict the coastline as a squiggly line. They don’t provide enough detail to really see the nooks and crannies, the rocky patches or marshy patches or beaches or what have you. You can’t really tell how what’s here now compares to what Marquette and Joliet and the Illinois saw back in 1673. We want to find maps that show what the coastline looked like when Chicago was first incorporated as a city, when the Great Chicago fire remapped the downtown, when they first built Navy Pier or built up the beaches of Rogers Park, etc.

So the Newberry Library (conveniently a WBEZ Partner, for full disclosure) is the next stop on our quest. Their curator will show us maps of the city going through the early 20th century. We’ll pick out the best ones and assemble them for comparison. Stay tuned!