Heroin moves to Chicago suburbs in small amounts through users

By Rob Wildeboer

Heroin moves to Chicago suburbs in small amounts through users

By Rob WildeboerGabriela Muro’s mother and stepfather live in a quiet townhome development in west suburban Aurora. The streets are named after trees and the uniform buildings are tidy. Next to the two-car garage is the front door, which opens to a two-story foyer with wood floors. When she was 15 years old Muro started making the drive from this townhome to Chicago’s West Side to buy heroin. The first time she went she made the trip with the friends who had introduced her to heroin.

“So I just remember like getting on 88 and then going to 290 and just going to this ghetto area off of Independence,” said Muro at a recent interview at her parents’ house.

Muro quickly got over her fear of Chicago’s West Side and started making the 60-mile round trip more and more often.

Muro had dealers that she used pretty consistently, a brother and sister that she liked. She’d call them on a cell phone and they’d ask her how much she needed and then they’d tell her where to go. She usually went to their house at Austin and Washington, but sometimes her dealers would be out and about and she’d have to meet them elsewhere.

“Many time’s I’ve had to go to the beauty salon where the girl was getting her hair done and just wait outside until she was done. Many times I’ve just had to go to their house and just have one of their family members come out and give it to us. We’ve had to go to family functions like cook outs,” said Muro.

Muro says she once went to Humboldt Park where the entire extended family was having a party. “And they were all in like, I guess, their little business. They all knew what was going on.”

The heroin trade relies heavily on networks. Dealers can’t advertise so they use word of mouth and reward users who bring in new business. “Oh yeah, like if we sent people their way they would hook us up with more bags,” Muro said. .

Muro introduced a number of her suburban friends to her dealer. She’s since realized that her friends who got her into heroin and took her to Chicago, they were doing the same thing. They were using her to get more for themselves.

As her addiction deepened, Muro sometimes found herself commuting to the West Side three times a day.

“Well we would spend our whole day just, we would wake up in the morning, go straight to the city, come back, get more money, go back to the city, we were constantly working on getting our next high. It was like a full-time job being a heroin addict,” said Muro.

I-290 is a trigger

Frankie Bauer has been clean for two months but this is his sixth time in rehab. He’s relapsed five times. He’s got to stay away from things that could trigger a relapse and the Eisenhower Expressway is definitely a trigger.

“Your stomach starts churning,” Bauer recounted in an interview at the Blue Island library near the sober living facility where he stays. “Dogs do that, they do that thing with the ringing of the bell. Ring a bell, show a dog meat. Ring a bell, show a dog meat ,and then ring a bell and the dog salivates. That’s how it is with heroin addicts on 290.”

Bauer is 22. He grew up in the western suburbs and remembers his friends prepping their syringes and cooking rigs in the backseat as they headed towards his dealer on Kostner just a couple blocks south of the Eisenhower. He says as soon as he got some heroin he’d pull into an alley and take two minutes to shoot up and then get back on the highway. Or sometimes, he’d shoot up in the parking lot of Rush hospital, which is nearby, just off 290. He and his friends knew the hospital because they also went there for drug treatment.

Bauer usually worked with the same dealer, but if his dealer didn’t have any dope he’d hit the blocks on the West Side.

“You just hop off of 290 at you know, you could go to Harlem, Austin, you could go to Cicero, Independence, you could just get off at any of those exits and all you gotta do is look for a guy standing on the corner, just ride up to him say, ‘Yo,’ he’ll ask you what you need, you’ll tell him and he’ll sell it to you and that’s really it,” said Bauer. “You could be pulling up and buying dope and the cops will just drive by. They don’t do anything about it and it’s disgusting how you could see people standing on the corner, and you know what they’re there for, and you know what you can score from them, and nothing was done.”

Of course, Chicago police do arrest lots of drug offenders, but driving around the West Side it’s easy to see why Bauer thinks nothing is being done. Such open drug dealing is much less common in the suburbs— one reason so many kids are commuting on 290.

Naperville police monitoring heroin users

“If they bring anything back it’s usually a small amount and they share it with their friends. So there’s not a hub here, where heroin’s being distributed, it’s basically Chicago,” said Naperville deputy police chief Brian Cunningham.

RELATED: The Chicago Reader‘s Mick Dumke on the business of drugs: The West Side’s main employer

Cunningham has spent much of his career either working, or overseeing, narcotics investigations. On his desk is a folder with the most recent crime statistics.

“This, the current year, we’re at three confirmed heroin deaths in Naperville,” Cunningham said last week.

That’s down compared to recent years when Naperville had as many as 10 heroin deaths but Cunningham says the number of overdoses has been consistent this year. He says that means kids are still using just as much as they did in 2011 and 2012.

“We have kids doing burglaries. We have kids doing thefts but they’re not actually dying from it so heroin is a huge, huge issue with us,” said Cunningham.

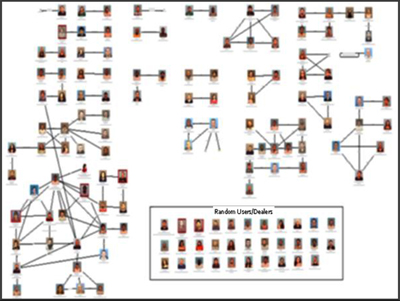

In his file of crime statistics Cunningham has a map of Naperville with little stars. The stars represent heroin users in town. Not dealers, or drug markets—users. The police are trying to keep an eye on every addict. It’s quite a contrast to Chicago’s West Side.

Cunningham says Naperville police will follow kids into the city and do surveillance of them buying drugs and driving back to the suburbs.

“The one thing about heroin addicts, from my own personal experience of dealing with them and arresting them and from the units, is that when you arrest a heroin addict, they’re very willing for the most part to tell you exactly what’s going on. It’s almost like they’re reaching out for help,” he said.

Cunningham admits that many addicts also share information hoping to get out of the station quickly and avoid dope sickness, the sickness that sets in when they don’t have access to heroin. And because heroin dealing relies so much on networks and relationships, heroin users know each other and can share that information with police.

Temptation too much

Gabriela Muro from Aurora was once arrested in the city of Chicago. She says she led police to a dealer she rarely used because she didn’t want to give up her main dealer, something that could have choked off her supply. She was also arrested in DuPage County by an officer who had been following them and recounted everywhere they’d been that day, including shooting up in a Walgreens parking lot and then getting back on the expressway.

Muro got probation a couple times and then was put in a drug court program, “and I did well for like five months but drug court placed me in a halfway house on the West Side, like literally a block away from my dealer’s house,” said Muro. The temptation was too much.

Eventually she got charged with breaking into houses and got two years. She’s glad she got such a long sentence. “If I would have gotten out I would have been doing the same stuff because for the first six months that I was in there I still wanted to get high,” she said. It took that long for her to get over her cravings.

Muro’s now been clean for three years, long enough. she says, that she can drive down the Eisenhower Expressway without wanting to pull off to buy some heroin.