Mental Health 911: Areas with most calls have fewest services

By Shannon Heffernan

Mental Health 911: Areas with most calls have fewest services

By Shannon HeffernanBoth Chicago and Illinois have made big cuts to mental health services in recent years. That has left managing mental illness on the plates of some people who never set out to do that job. People like police officers and jail staff.

The experiences of people who work in jails and police departments tell the story of a fraying mental health safety net, with big holes. The data I found on waiting lists, 911 calls, and on the location of mental health services, back their stories up.

When people leave Cook County Jail, they get a mental health hotline number and are told they can call anytime. The hotline is run by the jail, and Dr. Dena Williams is one of the people who might pick up.

She says the hope is that if people can call and get the help they need, including finding a therapist or psychiatrist, they would not be as likely to come back.

When I visited the jail, Williams sat feet away from her phone, in case she got a call. I asked her if she is usually able to get a caller into psychiatric services immediately.

“Immediately, as in before 30 days?” Williams asked. “I mean usually there is a wait. Sometimes the wait can be up to six months.”

This is the first big hole in the mental health safety net: waiting lists. Even thirty days can be a long time if you are in mental health crisis, but imagine keeping up with waiting lists without a phone or a place to sleep at night.

Calling the 36 mental health providers on the City of Chicago’s referral list, I found 14 of them—that is over a third—either had no outpatient psychiatrists or had closed their waiting lists. Two more had waiting lists around five months.

“The length of time it takes someone to receive medication is sometimes so long that they are unable to wait and they will end up right back in our custody,” Williams said.

One staff member at the jail said a guy told him he had gotten arrested for shoplifting on purpose.

The man said he was a patient at Tinley Park Mental Health Center and when that closed, the only place he knew to get medication was in jail. He said he hated being locked up. But he hated being actively psychotic more.

“It keeps me up at night. Because jail is not a place to be receiving treatment,” Williams said.

Clinic locations: a wheelchair with flat tires

Last year in Chicago, 911 took about 22,000 calls that had some kind of mental health component.

There is a special training officers can take to respond to these calls. It is called Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) training. The training is voluntary and only some officers take it.

On a recent Tuesday morning, 38 officers gathered at Mount Sinai Hospital for advanced training.

Most of the officers there had already been regularly responding to mental health calls. They had learned how to identify illnesses like schizophrenia, and how to admit someone to a hospital. Officers said doing this much work on mental health was something they never expected when they signed up for the police force.

Sgt. Lori Cooper helped lead the training. She stood at the front of the room and called on officers to take the next step.

“Here’s what’s happening right now: Someone’s decompensating. They come into our presence. We take them to the emergency room. They decompensate again. They come into our presence. We take them to the emergency room. They decompensate again. And we take them to where?”

The room replied in unison: “Jail.”

“What we are trying to do is break the cycle,” Cooper told them.

She also told the officers that breaking the cycle is going to take more than bringing people to emergency rooms. It is going to mean collaborating with clinics and hospitals to make sure people get regular treatment in their neighborhoods. Because if the services are far away, people won’t make it.

This is the second big hole in the mental health safety net: the location of services.

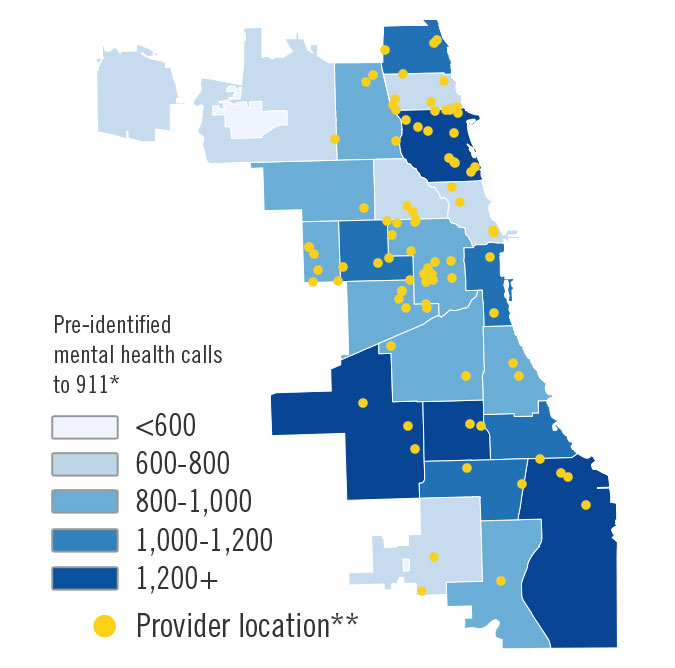

According to WBEZ analysis, some of the police districts where the most mental health 911 calls come from are also the districts with the fewest mental health services.

That means when officers respond to calls in those districts they are stuck with fewer nearby services where they can send people. Asking people to travel long distances for mental health care, “is kind of like putting them in a wheelchair with flat tires,” Cooper said.

As the Chicago Reporter recently reported, districts with a high volume of 911 mental health calls, are largely black and Hispanic.

The police department has a pilot program where they have paired up with a few mental health groups. It has a grant to help deliver services where and when the services are needed. It said it hopes this will patch up two big holes in the safety net—wait times and locations.

But for now it is just a pilot in a few districts. And even as this pilot launches, Gov. Bruce Rauner has proposed big cuts to Illinois’ mental health budget. Providers across the board told us if that happens, mental health services will fray even more.

In statements to WBEZ, the governor’s office blamed the budget mess on past misspending and said the proposed mental health cuts were not yet final.

Cooper said if any more services disappear, “We’re going to be asked to take them to services that might not exist, and so then there might be no alternative than to bring them to possibly jail.”

At an average cost of $143 a night at Cook County Jail, that might not end up saving taxpayers any cash.

Shannon Heffernan is a reporter for WBEZ. Follow her @shannon_h.

Map: Mental health calls to 911 by police district

*The number of mental health calls for 2014 was obtained from the Office of Emergency Management. Police officers said the number of calls may actually be higher than what is reported by OEMC, because the mental health component of a call may not be apparent until after officers arrive on scene.

**Mental health and substance abuse provider locations were obtained from The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) website. In addition to the marked location, some organizations may provide services at satellite locations or through traveling teams.