Picture This: Did The Art Institute of Chicago Ever Rent Out Paintings?

By Monica Eng

Picture This: Did The Art Institute of Chicago Ever Rent Out Paintings?

By Monica EngRobert K. Elder would love to decorate the walls in his living room with original paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago.

So he was floored when his friend Cyndy told him that back in the ’50s, her mom did just that. She said her mother claimed two particular pieces in their Naperville home were “on loan from the Art Institute.”

Whaaaaat?

This was hard for Robert to imagine. Like, what would that even look like? Someone strolling onto Michigan Avenue with a rented Monet stuck in his or her backpack?

So Robert wrote to Curious City and asked: Did the Art Institute really rent out paintings to the public at one time?

The short answer is yes. Back in the day, a group of women spearheaded a remarkable rental program that won the Art Institute a lot of praise at the time. But despite those accolades, the Art Institute mysteriously mothballed the program 33 years later. And that leads us to another question: Why would the museum shut down what appeared to be a successful program that not only rented out artwork to the public, but raised money for the museum and boosted the careers of local artists?

Allow Curious City to be your curator for this little-known history of one of the city’s oldest cultural institutions.

Putting up the ‘For Rent’ sign

In 1954, the women’s board of the Art Institute unveiled the Art Rental and Sales Gallery, which made original art affordable to average citizens, created a new revenue stream for the museum, and helped support nearly 2,000 local artists, according to museum records and interviews with people who were involved in the program. The Art Institute declined interview requests for comment.

The rental gallery was the first of its kind in Chicago, but it took inspiration from similar programs at other museums, like New York City’s Museum of Modern Art, according to Art Institute records.

The Art Institute’s rental program assembled an affordable collection of framed works and sculptures — completely separate from the museum’s permanent collection — and rented or sold pieces to the public, according to museum records. The motive was to raise money for the museum, help consumers appreciate modern art, and forge stronger ties to the Chicago art community.

During its first year, the gallery showed artwork from 80 juried Chicago artists, rented 346 pieces, and sold 35, according to museum records. At the time, the top price to purchase a piece was $500. Renters paid between $2.50 to $25, could keep artwork for two months, and had the option of buying the work. Each item was insured under a museum policy against theft and damage. Paintings not returned on time could land the renter in court.

Within a short time, newspapers took notice of the program. In 1959, Chicago Daily News reporter M.W. Newman wrote:

“Doctors, lawyers, possibly Indian chiefs and certainly housewives are renting paintings at the Art Institute these days. The ladies are among the best customers. Some of them are finding it more fun than bargain-hunting in supermarkets. Not all of them know their art as well as their onions, although many do. But they usually know what their husbands don’t like.”

‘Housewives’ were onto something

Despite the condescending tone toward housewives at the time, the women’s board (made up of mostly well-heeled Chicago wives identified in museum documents only by their husbands’ first and last names) had launched a program that featured a veritable who’s who of emerging Chicago artists. These included Roger Brown, Ed Paschke, Gladys Nilsson, Jan Miller, Richard Hunt, and Jim Nutt, according to Marta Pappert, who was the rental gallery’s executive director in the ’70s and early ’80s.

Chicago painter Winifred Godfrey said she credits the program with launching her long, successful career.

“I had a great admiration and loyalty to the Art Rental and Sales Gallery because it provided exhibition opportunities to young Chicago artists at a time when there were few galleries. I was very upset when the program was discontinued,” she wrote in an email to Curious City. “It is my belief that the ARSG gave me an initial opportunity to show my artwork to a class of patrons that I would not have access to in another circumstance.”

Women’s board members often came in from the suburbs to volunteer at the gallery, visit artists, and help corporate clients choose pieces for Chicago office buildings.

“I loved that part of it,” said former women’s board member Traute Bransfield, 92. “We’d go out to some very fancy offices at the Sears Tower and see all kinds of famous people in the First National Bank building. … We made money for the women’s board of the AIC and the artists.”

Indeed, corporate participation in the program helped sales greatly, as companies often snapped up several paintings at a time to rent and display in offices, lobbies, and warehouses. Goldblatt’s department store even rented art from the program for its window displays, according to Art Institute documents.

A reach beyond the museum’s walls

Early on, the program helped acquire art for several Chicago public schools. Within the first few years, it was also holding exhibitions outside the Art Institute’s walls. These included suburban venues, Navy Pier, the Chicago Sun-Times building, and WFMT’s studios.

By the 1970s, the gallery was housed on the lower level of the Art Institute, where the slide gallery is today. Rental fees rose to a minimum of $5, and the top price for a piece was hiked to $2,000. The selection had expanded beyond sculptures, paintings, and drawings to include limited-editioned prints, woodcuts, and even photography.

Packing up the paintings

During its 33 years, the Art Institute’s rental program paid more than a million dollars in sales receipts to local artists and contributed $270,000 to the museum, according to Art Institute records.

But by the late ’80s, the museum was seeking more room for its permanent collection, records show. And, according to Peppert, some of the trustees were not enthusiastic about the program.

“I think they saw it as a little Mickey Mouse [and] not very serious compared to the rest of the museum,” she says.

These factors were coupled with serious concerns from the Art Institute’s security department about the potential for thefts, Peppert says.

“The gallery had a tremendous amount of traffic, people carrying artwork in and out of the Art Institute,” she recalls. “I had to sign a pass every time and, as far as I know, nothing was ever stolen by doing this but there was a potential, so the security department was not a big backer for that reason.”

In 1987, the Art Institute shut down the rental gallery, and unsold artwork had to be picked up by the artists. The women’s board threw a final luncheon called, somewhat bittersweetly, “Let’s Celebrate,” and the rental gallery faded into an obscure footnote in Chicago art history.

“I don’t think there has ever been again anything quite like it,” Peppert says. “We had so many different kinds of artists, and we had a relatively large space at the Art Institute. It was very inclusive, even though the artists and their work had to be juried in. It was just a really special place.”

When I bring this information to Robert, he’s glad to hear it really existed.

“I think it’s an incredible piece of history and I wish they’d do it again,” he says.

Do other museums rent out parts of their collections?

Sadly for Robert, the Art Institute says it has no plans to revive anything like the rental gallery anytime soon.

But this fall, the University of Chicago’s Smart Museum revived its Art to Live With rental program for students. The program, which originally began in the 1950s but ended in the ’80s, features 75 works that include prints by Pablo Picasso, Marc Chagall, and Joan Miro.

Smart Museum Director Alison Gass says students were excited about the program’s return.

“Some even brought chairs and blow-up beds to wait in line all night,” she says. “And, yes, the first to go were the Picasso and Miro, but there are a lot of fantastic pieces.”

While the Smart Museum’s program is limited to those living in U of C dorms, another Chicago institution offers the general public a chance to rent items from one of its collections. The Field Museum’s N.W. Harris Learning Collection rents out more than 1,500 cultural, botanical, musical, industrial, and biological items to visitors who buy a $10 membership. The museum offers different rental plans that range from $10 for one item to $100 for 40. The one exception is a life-sized reproduction of a Tyrannosaurus rex skull that costs $200 to rent.

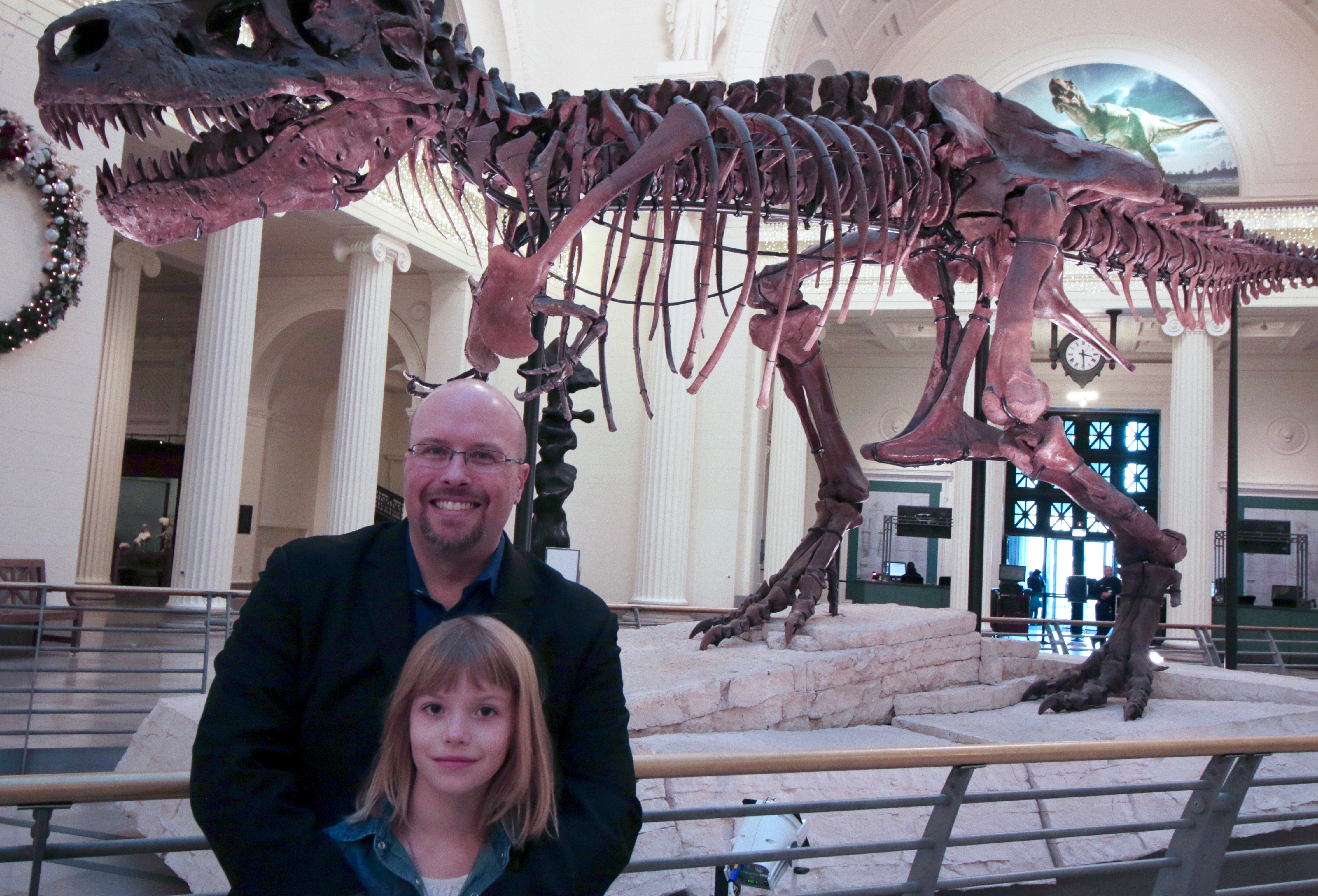

More about our questioner

Robert K. Elder is a Chicago-area author and tech and media executive (and this reporter’s former colleague at the Chicago Tribune). Robert is a longtime Chicago journalist and former executive at Crain Communications, the Chicago Sun-Times, and DNAinfo. He’s the author of eight books, which include The Film that Changed My Life, It Was Love When, Hidden Hemingway, Last Words of the Executed, and the upcoming The Mixtape of My Life.

Robert is also passionate about startups and entrepreneurship; he serves as a mentor at 1871 Chicago and TechStars.

Most importantly, he’s the dad of nine-year-old twins and says he is married to an “amazing woman who tolerates his love of movies, poker, public radio, museums, and odd family road trips off the beaten path.”

He’s an Art Institute member and says he wishes the museum would share more information about its historic art rental program.

He also loves Curious City and thinks it should be syndicated nationally as Curious Nation.

Monica Eng is a reporter for Curious City. Follow her at @monicaeng or write to her at meng@wbez.org