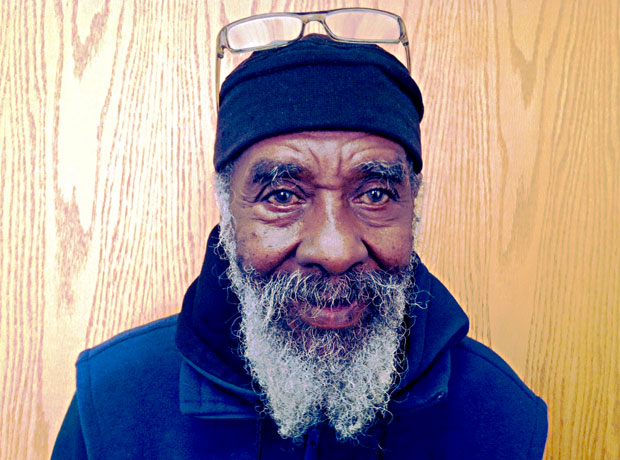

Ronn Pitts: Breaking color barriers, building community

By Alison Cuddy

Ronn Pitts: Breaking color barriers, building community

By Alison CuddyAmerican Revolution II: The Battle for Chicago starts with footage familiar to many Chicagoans: the armed confrontations between police and protestors at the 1968 Democratic National Convention. But the film then moves to far less familiar — and in many ways more remarkable — ground.

In a pivotal scene, the Young Patriots, a group of poor, white, southern activists fighting forced evictions and gentrification on Chicago’s North Side, meet a tall, charismatic, community activist: Black Panther Bobby Lee. At first the atmosphere is uncomfortable and silent. Then, Lee starts to work the room, grabbing people by the shoulder, tapping them on the knee. Through a series of exhortations, mainly “Right on!” and “Let’s move!” Lee wins people over. One by one they begin to testify about their experiences with what Lee calls the “concept of poverty.”

This moment of racial solidarity was captured on film thanks to a Chicago collective known as The Film Group, which spotted the deeper story of community behind the barricades. American Revolution II screens this Sunday as part of the monthly film series The Black Cinema Is… Attend the event and you’ll have the chance to meet one of the film’s creators: Bronzeville native Ronn Pitts.

Pitts, 75, has lived a life with Zelig-like qualities: He has found himself in the midst of history-making events time and again.

“We were the first blacks to shoot for any professional football team ever,” Pitts said. He also recounted adventures like filming during the 1965 march to Selma, Ala., and being “kidnapped” by Muhammad Ali to document the boxer as he prepared for his big fight against George Forman in 1974.

Pitts got into film by working as a shipping clerk at a camera rental company, a job his mother got him (before that he was a bookie placing bets on horses). But shooting films was a major struggle. “There were no blacks shooting [news] cameras until 1973,” he said. “There were no women, no blacks — nothing but white males.”

In the early ’70s, Pitts, Kartemquin’s Jerry Blumenthal and others eventually set up shop with the Community Film Workshop at Columbia College. They sent students out to cover news, including fires or speeches by the mayor. “That was a great experience, because then I recognized what prejudice truly was,” Pitts said. “Those old men, they would cut their cords,” and challenged him for training minorities.

Pitts eventually left Chicago, settling in San Francisco for 17 years. While there, he captured the death of gay rights pioneer Harvey Milk on film. He was in the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem the night Malcolm X was assassinated (Pitts said his footage was seized by police). And, he was behind the camera the day Chicago Bears wide receiver Chuck Hughes died of a heart attack on the field. Pitts said those moments were the “shocking things” about filmmaking. “You can’t take it back,” he said. “And you sleep with that at night, knowing that you captured death in your lens.”

Despite his heavy experiences, Pitts has retained a light and joyful spirit. He took up tap dancing two years ago, just for fun. He is patient with his students, but he’s not afraid to mix it up with those who try to harass him. Like any good son, he credits his mother, Elizabeth Pitts, for his attitude. His mother welcomed anyone without a home into their house and Pitts recently bought a house near his, which he hopes will one day be a space for ex-convicts. That combination of tender and tough is also something he attributes to his mother, who Pitts said was fiercely protective, once brandishing a butcher knife against whites who picked on her children.

“She was a fighter,” he said. “And I’m a chip off her block.”

American Revolution II screens Sunday Nov. 18 at 4 p.m. as part of The Black Cinema Is… monthly film series at the Rebuild Foundation in Chicago. Ron Pitts will speak at the event, but space is extremely limited. Find out how to RSVP here.